It’s a bright and clear morning. The sun is beating down on the Appleby Blue almshouses in Bermondsey. Two older men, tops off—as is customary when the sun unseasonably appears in London—are soaking it up on the roof gardens of the new building’s southern edge. The almshouse was recently completed by Witherford Watson Mann for the 500-year-old charity United St Saviour’s. “You can’t really be disappointed living here,” one said, having just been rehoused from a site down the road that awaits redevelopment. The rooftop gardens are already lush and blooming, brimming with produce grown for the community kitchen. Downstairs, the kitchen spills out into a double-height dining space lined with solid oak and grids of glazing. Inset sliding doors sweep out onto a garden courtyard, which is filled with sunlight, thanks to the building’s stepped profile to the south. The calming acoustics of a linear water feature trickle through mature ginkgo trees. This is social housing, but you would not know it at first glance.

The London Borough of Southwark is a microcosm of the U.K.’s housing crisis. Southwark is the U.K.’s largest local authority landlord, managing 55,000 homes, which house 40 percent of the borough’s residents. While its northern edge abuts the River Thames and touristic icons like Tower Bridge, Tate Modern, and Shakespeare’s Globe, Southwark is a battleground for housing. There are more than 20,000 people on its council house waiting list, with many others living in overcrowded temporary accommodation—and the situation only becomes more dysfunctional in the private sector.

It’s a bleak picture, but one of the things that exacerbates the complex set of housing problems is a lack of secure and affordable housing for older people, many of whom received decent family council houses in the postwar building boom. These lucky few are therefore unlikely to move out and free up the desperately needed larger homes in the area.

“What we didn’t want was to create another retreat from society in a typical sheltered housing block,” explained Martyn Craddock, chief executive of United St Saviour’s. The charity operates the almshouses and has tall ambitions in the face of decades of neglect and harmful policies in the social housing sector. “We think this is an example of what social housing in the inner cities should be…and the social benefits are huge.”

Almshouses date back to a much more compassionate time of housing provision in London and have existed since the tenth century as a way to provide affordable accommodation to vulnerable groups. They are widely regarded as the oldest form of social housing in the U.K. and were most often started by religious orders or individual wealthy benefactors. However, the surviving picturesque rows of cottages of the oldest almshouses obscure the basic and often impoverished accommodation they once provided. Social norms and moral enforcements meant that residents were made to follow strict rules and worship, and these behaviors are reflected in, as well as dictated by, the architecture of the almshouses themselves. The designs are inward-looking, often arranged around central courtyards, with the houses turning their backs to the street. There was shame associated with those being sent to live there: An almshouse address indicated that you could not be provided for by your family. Also, more recent studies have suggested that almshouses could be responsible for the widespread ageism in the U.K. since the 18th century, as they removed, and therefore isolated, older people from both the family home and greater society.

Today, though, the need for affordable housing is taking on a new urgency, and Appleby Blue attempts to subvert this troubled history. The brick building with two-story oak bay windows framing the entrance is home to 57 units with a nonstandard breakdown of type: 53 are one-bedrooms, two are two-bedrooms, and two are studios that specifically host yearlong residencies for academics conducting on-site research into the effects of food growing, cooking, and eating together on the residents’ well-being.

The flats are designed to the London mayor’s minimum space standards and mostly do not exceed them. But as Stephen Witherford, director at Witherford Watson Mann, explained: “This isn’t really about provision; it’s always been about trying to create a really good quality of life.” The space standards dictate that every new unit should have some private amenity space, which is most often provided in the form of a balcony. In discussion with residents at another of the providers’ almshouse sites, Witherford explained that they remarked: “What’s the point of sitting on our own on a balcony? We sit [by ourselves] all the time.”

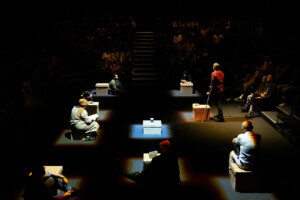

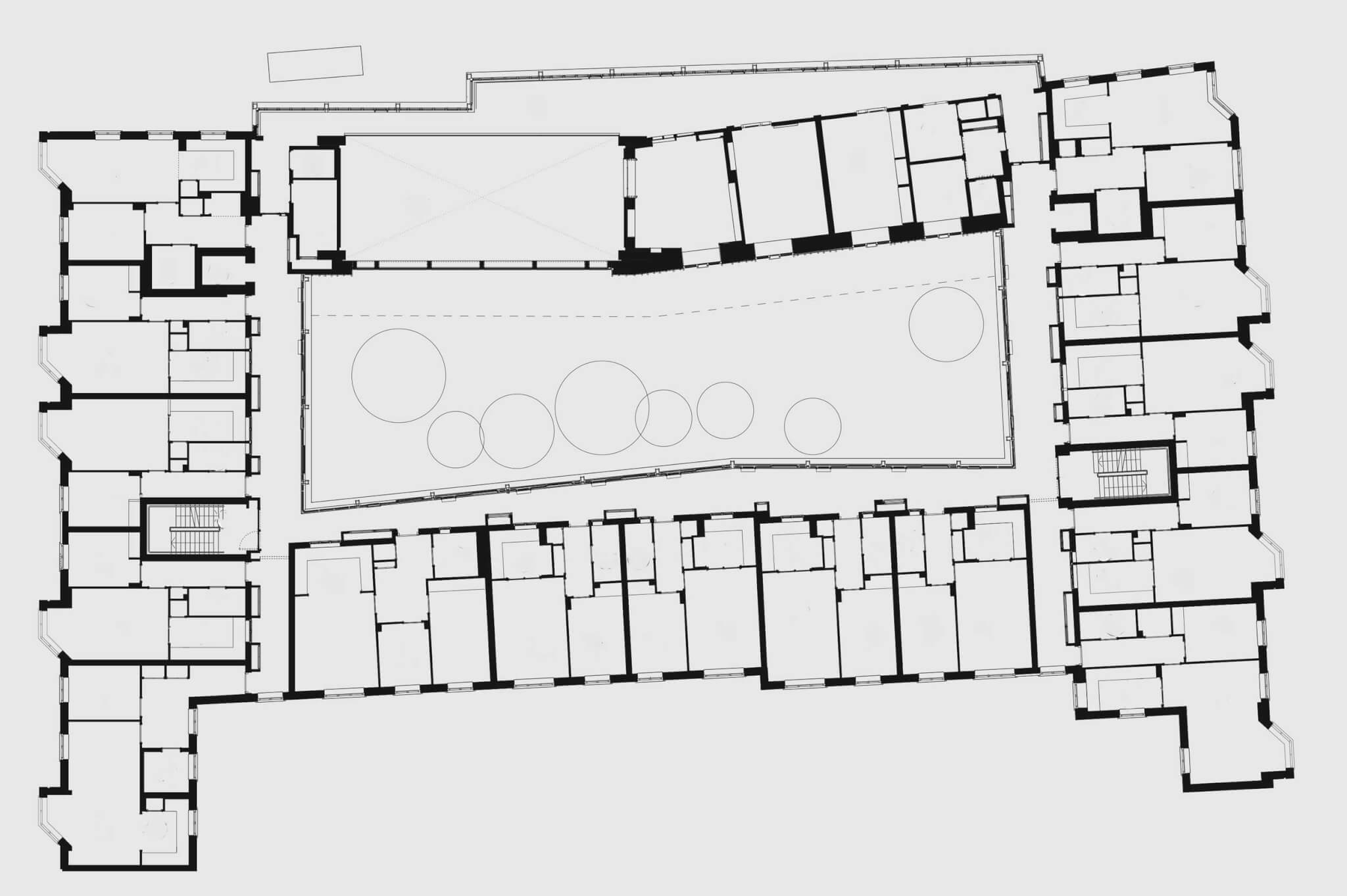

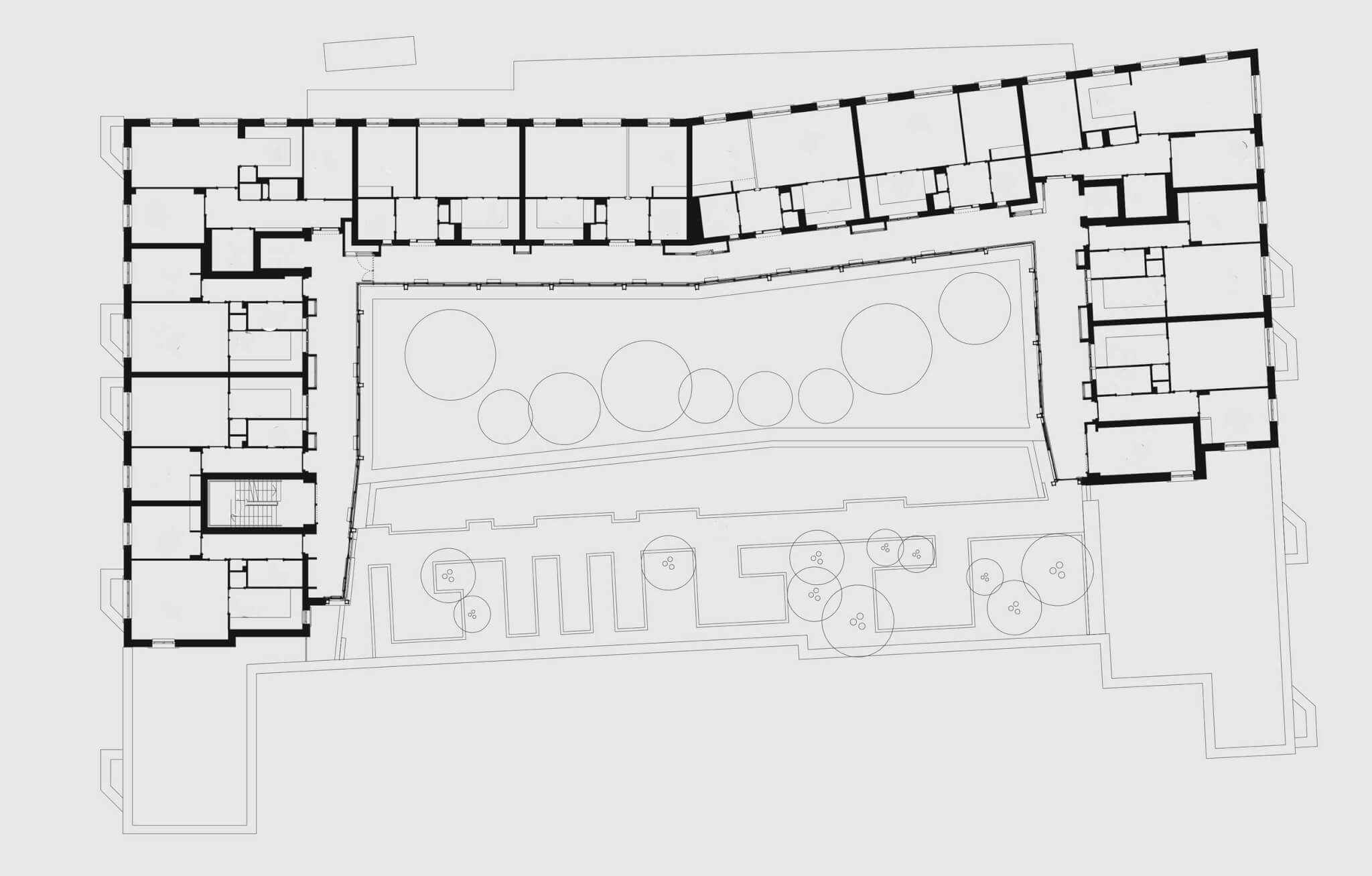

It was important to United St Saviour’s to combat loneliness through the design and provide spaces for informal socializing. These conversations prompted ideas to prioritize collective amenity spaces over private ones. Witherford Watson Mann negotiated with Southwark Council that in place of private balconies, wide walkways would line the inner courtyard, catching the sun and creating a quiet place to sit with other residents. Forming winter gardens, the entrance routes to all flats double as a social space, with large sliding windows, planters, and benches. “The real effort and energy in the building is in all of the in-between spaces. This is about a joyful life,” Witherford said.

All prospective tenants were interviewed before moving in to ensure they would like the social nature of the development and be involved in the community. The development is now full, with more than half of the new residents being nominated by the local council from its waiting list. But the other half was selected by United St Saviour’s across a broad spectrum of age, need, and ethnicity to, as Craddock describes, “fabricate what we think is a natural community of older people in this part of London.” Under the almshouse legal structure, residents are appointees instead of tenants, and rather than rent, they pay a maintenance fee. At Appleby Blue, the maintenance fee is £200 a week (in Southwark you can expect to pay double this for a one-bedroom apartment), and this cost is fully offset for many by the council’s housing benefit, which can be up to £300 a week.

In the community kitchen, I sat down for lunch with one resident named Gloria. “I’m in love with it,” she told me. In stark contrast to her previous council flat, plagued with the trials of maintenance and basic upkeep, she insisted, “I’m not going nowhere now.” I can understand why. The development does feel luxurious—it’s easy to consider this a luxury development when the norm of social housing provision in the U.K. has become the absolute bare minimum. For this type of housing to be dignified and joyful was once beyond our collective imagination. In reality, the flats are not bewilderingly high-spec, and they needn’t be, because the joy is provided for in the communal space. The oak-framed frontage to the main road has a second-floor landing that has been dubbed “the royal box,” where residents spill down in the evenings with food and wine to watch London play out on Southwark Park Road. On a recent Saturday night, one resident described an evening in the royal box waving at some local teenagers over the road, drinking their own wine, both groups peering into each other’s lives. He’s reminded: “Us and the teens, we’re not so different.”

Ellen Peirson is an architectural designer, writer, and editor based in London.