Grenfell: In the Words of Survivors

Written by Gillian Slovo, co-directed by Phyllida Lloyd and Anthony Simpson-Pike

St. Ann’s Warehouse, 45 Water Street, Brooklyn, New York

Through May 12

“A trial resembles a play in that both focus on the doer, not on the victim.”

—Hannah Arendt, 1963

What can New Yorkers learn from a lethal building fire that happened in London seven years ago? I recently found myself asking this question en route to see Gillian Slovo’s brilliant play, Grenfell: In the Words of Survivors, at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The performance, co-directed by Phyllida Lloyd and Anthony Simpson-Pike, recounts the harrowing story of the 2017 Grenfell fire, a catastrophe that claimed 72 lives once dubbed the “the most appalling example of institutional failure in recent British history.”

Grenfell: In the Words of Survivors began with multiple performances in London starting in July 2023 and eventually made its U.S. debut on April 13 in Brooklyn. It features an 11-person cast where professional actors such as Dominique Tipper, Ash Hunter, Mona Goodwin, Keaton Guimarães-Tolley, and others play the roles of actual Grenfell survivors including Natasha Elcock, Nick Burton, Hanan Wahabi, and Tiago Alves, respectively. The performance at St. Ann’s Warehouse is accompanied by a photography exhibition, Gold & Ashes, by Feruza Afewerki on view in the lobby. Set and costume design was by Georgia Lowe.

Slovo’s Grenfell is an attempt at retelling the fire’s very complicated story with seemingly endless moving parts within a three-hour window of time (split by a 15 minute intermission) in all of its complexity and human emotion. It’s a two-act immersive play in a black box theater. The performance uses a “Theatre-in-the-Round” configuration where the audience surrounds the actors from all four sides, a common layout throughout ancient Greece and Rome that was later repopularized by Bertolt Brecht. The only props actors use are cardboard boxes: These represent the containers that survivors were forced to hastily store their possessions in after vacating the smoke-filled Grenfell Tower the night of the fire.

In her rendition, Slovo doesn’t masquerade behind any facade of neutrality. She said last summer that those responsible for Grenfell “should be jailed for what happened.” The play builds upon Slovo’s long career exploring complex political issues through the prism of avant-garde theater.

Past works by Slovo delved into human rights abuses in Guantanamo. They also touched upon South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Committee after the fall of apartheid, a topic that was deeply personal for Slovo, a South African emigre now based in London. (Slovo’s parents are Joe and Ruth Slovo, two bonafide members of the South African Communist Party who fought tirelessly alongside Nelson Mandela to end apartheid.) Now, Grenfell is the latest political drama Slovo sought to address on stage, and she doesn’t pull any punches.

Act One

Thanks to the 24-hour news cycle, the Grenfell fire seems like it happened ages ago. But there’s still so much it can teach us, even here across the pond.

The uncontested facts are: On June 14, 2017, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, a 24-story highrise caught on fire, and 72 people were killed; and the wide majority of victims were working class people of color. The inferno rightfully sparked outrage and a fusillade of finger pointing ensued. The London Fire Brigade drew ire for ordering residents to stay in place, as did the property management company, Rydon, who clad the building with combustible materials and installed confusing signage throughout Grenfell’s egress points. And then there were the building material suppliers—Arconic, Celotex, and Kingspan—that the architects, Studio E; the contractor, KCTMO; and facade specialist, Harley Facades, elected to work with during the building’s 2015–16 renovation.

The beginning of Act One talks about life before the fire, and how good it really was. It has stories from former residents about what the Brutalist building meant to them. One woman, Turufat Yilma (played by Nahel Tzegai) tells her story of immigrating from Ethiopia, and the sheer joy of moving into Grenfell after her arduous journey. “The tower was one big family,” Maher Khoudair said. “Every floor had smells of different cuisines,” Rabia Rahya chimed in. “And different music. Moroccan music on the top floor and then in the middle layer someone listening to reggae music.”

Maher Khoudair (played by Gaz Choudhry) retells what it was like fleeing his war-torn home country of Syria and relocating his family to the U.K. Khoudair had polio as a child and used crutches. His story tells the audience what it was like trying to escape Grenfell as a disabled person. (Khoudair notes that 42 percent of disabled Grenfell residents died in the fire.) Thus, the opening act is meant to humanize the victims who were quickly reduced to numbers in the wake of disaster.

After these heartfelt accounts, Slovo zooms out with a history lesson for context. Act One retells how Margaret Thatcher’s government repealed a law in place since the Great London Fire of 1666. (In the 17th century, after the 1666 fire that burnt down much of the city, parliamentarians issued an edict that forbade combustible materials from being used on the exterior of buildings, thus explaining much of London’s masonry and concrete construction.) Slovo then masterfully brings the audience through a brief history of Grenfell from the time it was built in the 1960s through Thatcherite London, when council housing was privatized en masse thanks to Right to Buy, a provision passed in 1980.

Slovo’s account then guides the audience to 1991, when Thatcher infamously approved Document B—a bill which lifted the combustible material ban from 1666—thus opening the doorway for property managers to cut corners and use cheap flammable materials on the facades of their properties, like Grenfell. Then in 2014, David Cameron further hacked away at building regulations in the name of “innovation” to spur quick and dirty construction, policy decisions that inevitably had fateful consequences.

Act Two

Overall, Grenfell is brilliantly researched, and the three hours whizz by in what seems like minutes. The writers certainly did their homework: The actors on stage dramatized the Notting Barnes South Final Master Plan Report from 2009 which first proposed demolishing Grenfell Tower to make way for luxury development in the fast gentrifying neighborhood. It also showcases the Grenfell Action Group, a tenants organization that formed in 2012 because the tower was being “allowed to deteriorate into a slum.”

At one point, the show gets extremely architectural when Tiago Alves (played by Keaton Guimarães-Tolley) explains how the facade cladding system contributed to the fire’s spread, assisted with a technical building section (by video designer Akhila Krishnan) projected on monitors.

In Act Two, Slovo plays chilling phone conversations between dispatchers and Grenfell residents while the building burnt. The stage set leverages a series of television monitors that encircle the performance area above the audience. There, real life episodes from the public inquiry are re-enacted, such as one shameful exchange between Kingspan’s Ivor Meredith and a magistrate. The artistic device is similar to Slovo’s earlier dramatization of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Committee where, in the 1990s, perpetrators of atrocious crimes had to look the families of their victims in the eye, and admit their wrongdoings.

Watching the public inquiry re-enactments, my blood boiled when actor Michael Shaeffer stepped into the shoes of Arconic president Claude Schmidt. During the public inquiry, Schmidt (played by Shaeffer) said the company’s decision to use flammable material was “risky,” and leaves it at that.

When Schmidt is on trial, one can’t help but recall Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963). Indeed, both works by Arendt and Slovo show how reprehensible atrocities often aren’t committed by brazen heathens, but rather sleepy middle managers that were just doing my job as they say. “A trial resembles a play in that both focus on the doer, not on the victim,” Arendt famously noted. “Is this a textbook case of bad faith combined with outrageous stupidity?”

Coda

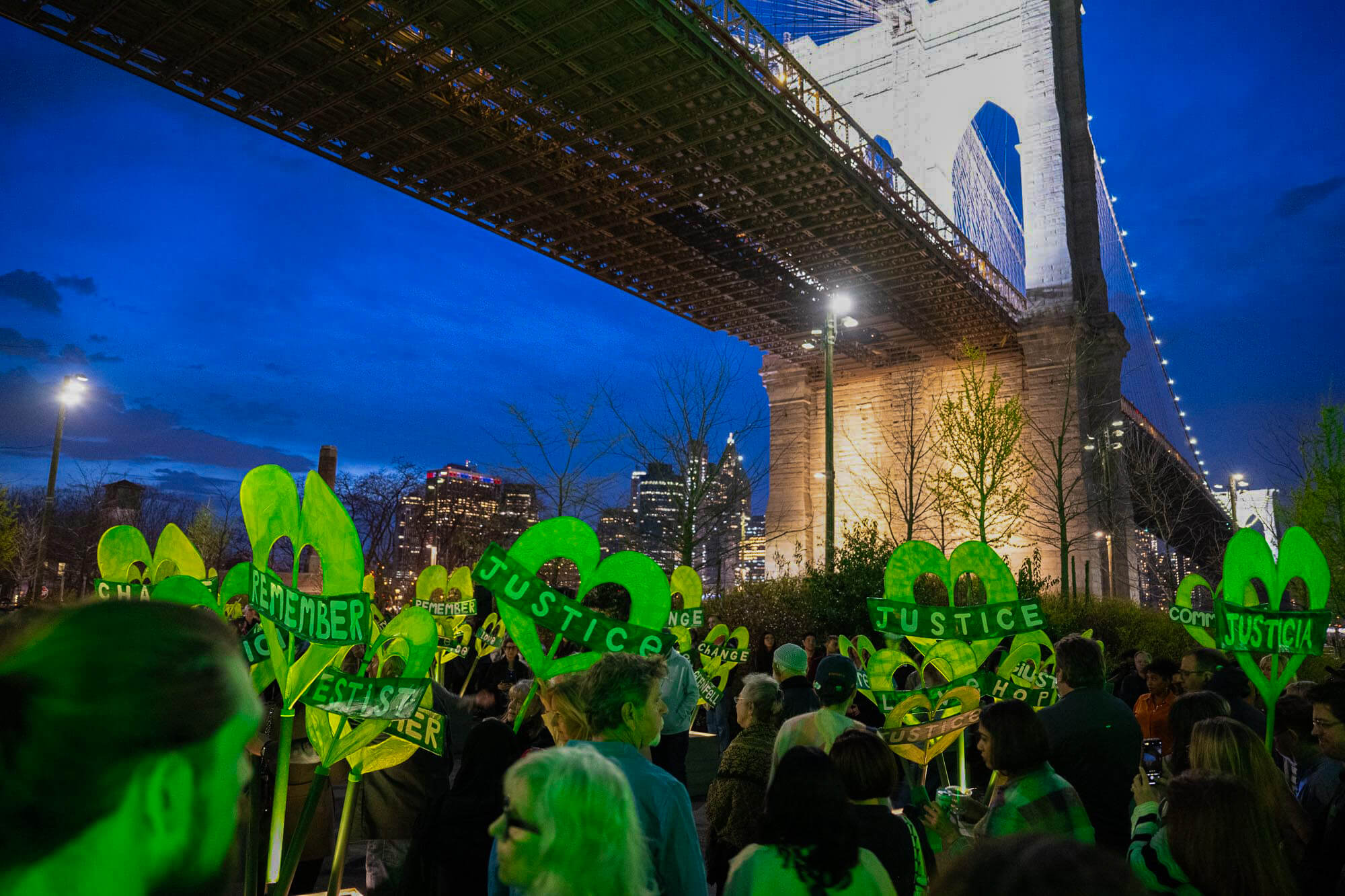

The performance ends with a film screening of survivors and their friends and family. Actors then request viewers to lift from their seats, and follow them outside in silence, much like the protests for Grenfell in London on the fire’s fifth anniversary in 2022. Actors and audience members blend into one body at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge and look out into the New York night sky holding signs with messages like “JUSTICE” and “GRENFELL FOREVER.”

As a journalist who covers public housing, I couldn’t help but draw parallels between pre-Grenfell London and where New York is now. Throughout Grenfell, my mind was saturated with images of Twin Parks North West in 2022, where 17 people were killed in the Bronx from an electrical fire.

In the last decade, a new housing program began in New York which seeks to transfer 62,000 units of public housing into the hands of private management companies in the next few years, much like Margaret Thatcher’s 1980 Housing Act. From the get go, NYCHA residents and human rights groups have reported complaints about the privatization program, PACT/RAD. Whether these programs truly improve the lives of New Yorkers remains to be seen.

If anything, Gillian Slovo’s Grenfell puts the writing on the wall. It shows that selling off public housing stock to the highest bidder is never an adequate substitute for solid government investment in housing and that, when housing itself is considered a commodity versus universal human right, there will always be abuses.

Above all else, Grenfell reminds us: Sure, this happened in London, but it can happen here too, unless we take a stand.

Grenfell: In the Words of Survivors is on view at St. Ann’s Warehouse through May 12.