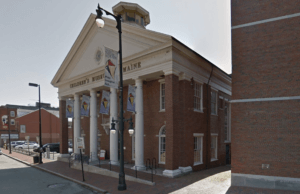

Last week, Philip Johnson’s Brick House—the unassuming partner to the architect’s famous Glass House—reopened its doors in New Canaan, Connecticut. After being closed to the public for 17 years, the National Trust for Historic Preservation will now include the Brick House on tours of Johnson’s idyllic property.

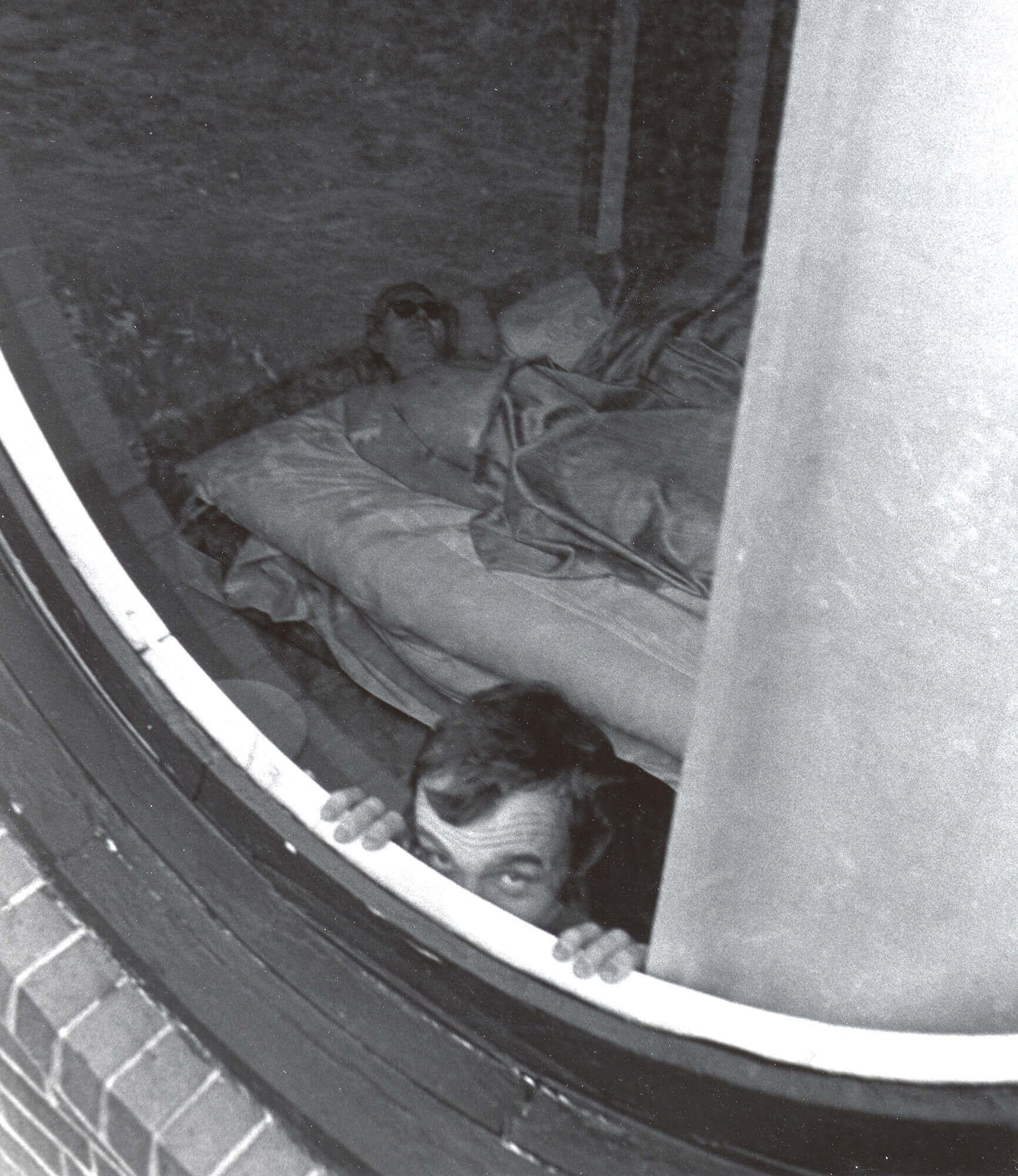

Known colloquially to the late Johnson and his partner, curator David Whitney, as the “Guest House” the squat brick prism hosted its share of celebrity company, including Andy Warhol, Paul Rudolph, and Phyllis Lambert. But the structure also served as a refuge for Whitney and Johnson from the privations of The Glass House, namely the home’s sweltering solar heat gain during the summer and obvious lack of privacy.

On April 30, a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Brick House was held in conjunction with a celebration of the site’s 75th anniversary and the opening of The Paper Log House, designed by Shigeru Ban. Opening remarks were delivered by Paul Goldberger, former architecture critic at The New Yorker and chairman of the Advisory Council of the Glass House, Kirsten Reoch, the recently appointed executive director of The Glass House, and Omar Eaton-Martinez, senior vice president for historic sites at the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

During the reception, AN spoke to Mark Stoner, the Graham Gund Architect for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, who described the challenges of the renovation process.

“There was nothing on this project that we didn’t touch” he said. “From roofing to masonry, to the foundation, mechanical vault, site drainage, and interiors. 860 gross square feet, we touched all of it.”

The grounds of The Glass House first opened to the public in 2006, shortly after the death of Whitney and Johnson. Initially included on tours of the site, the Brick House was quickly closed due to mold from periodic water infiltration: The structure’s greatest design flaw is its placement, sited at the bottom of a steep hill. During rain storms this hill channels water from the road down to the foundation of the Brick House, resulting in near-constant flooding since its initial erection in 1950.

To more efficiently manage drainage, Stoner and his team have implemented a triple redundant system. “Up the hill we have a drain curve, which is a physical barrier that collects and diverts water,” said Stoner. Two additional redundancies were installed at the Brick House: a foundation drain along the perimeter of the structure, as well as surface drains on the lawn.

“People have asked what the hardest part [of the renovation] was, it was absolutely the drainage.”

The interior was also subject to a major overhaul. Edward Fields Carpet Markers, the original fabricator of the rugs in the reading room and bedroom, donated recreations of their original work. Additionally, Venetian textile designer Fortuny reproduced the piumette patterned fabric panels which cover the bedroom walls. New porthole windows, carefully crafted to match the originals, were installed, as well as new skylights.

Constructed in 1949, the Brick House predates The Glass House by several months. The pair is spaced on opposite sides of a grass lawn and connected via a diagonal gravel walkway. This path crudely traces the route of a narrow tunnel which routes power to the Glass House from mechanical systems concealed within the Brick House.

Clad on all sides in Flemish bond masonry, the Brick House is opaque save for three porthole windows across its back face. In plan, the structure possesses the same 56 foot length as its glass counterpart, but is only half as deep. Originally divided into three equally-sized rooms (each corresponding to one of the three porthole windows), the architect combined two of these to create a large bedroom. The adjoining space—a library holding Johnson’s personal collection of books—as well as a bathroom located at the end of the entrance hallway would undergo several redesigns during Johnson’s lifetime.

The rooms are connected by a narrow corridor affixed along the building’s entrance elevation. Bare and white, the hallway’s sole decorations are a collection of framed etchings by the artist Brice Marden. This passageway is capped on either end by paired doors that have been simplified through a unique detail: Their height has been extended above the frame’s lintel, allowing it to close flush with the wall.

Most of all interior elements, the restored bathroom best signifies Johnson’s departure from the modernist influence of his mentor, Mies van der Rohe. Classical ornamentation and the use of deep veined marble in the washroom foreshadowed Johnson’s future as one of the great exporters of postmodernism.

Next to the bathroom is the library. Lit by one of the three porthole windows, the reading room is abundantly colorful, formed from the complement of mint-green walls, yellow curtains, and a wall-to-wall purple rug. Two of the late Gaetano Pesce’s Feltri chairs sit beneath the large circular window.

In the bedroom, Johnson installed a sequence of sloping white vaults that frame a bed as well as Ibram Lassaw’s wall-mounted sculpture, Clouds of Magellan, a three-dimensional knot of welded bronze and steel.

Strange acoustic effects occur beneath the vault. Sound travels along the curved underside of the structure creating a whispering gallery effect. A similar phenomenon occurs in the vaulted corridors of Grand Central Terminal where a whisper uttered on one end of the vault can be heard clearly on the other side. Within the Brick House, this effect manifests on a much more intimate scale.

As many have previously noted, the opaque design of the Brick House functioned to conceal Johnson’s sexuality. The soft textures of the bedroom—fabric walls, plush furniture, and early use of dimmer switch technology—evoke a Freudian resonance, creating a womb-like safe space sealed from the prejudices of the outside world.

The Brick House also conceals artifacts from Johnson’s foray into reactionary politics during the 1930s. Biographies of Huey Long and Adolf Hitler remain on the shelves of his personal library. During his lifetime, Johnson was careful to avoid discussion of his past political affiliations and the issue was largely ignored by the architectural community.

Recent years have fostered more open academic discussion of Johnson’s politics and sexuality. The reopening of the Brick House will allow these hidden attributes to be reconciled with the architect’s public image.

With the Brick House restored, the National Trust for Historic Buildings is now able to present a complete Glass House site to the public, showcasing how Johnson’s taste and practice evolved throughout his lifetime. The architect used the sprawling property to experiment with the conventions of domesticity and suburban life. Acting like an exploded domicile, the landscape mediates the separation of residential programs (library, guest room, gallery), which are each treated to an independent structure. Most importantly, visitors can now experience the dialectic opposition between public and private space demonstrated by the Glass and Brick House, structures that were originally designed as an inseparable pair.