Photo City: How Images Shape the Urban World

Victoria & Albert Museum Dundee

Through October 20

Most of us know the standard tourist factoids of the Eiffel Tower: It was only meant to be temporary, and it was famously unpopular among Parisians at the time. But what you might not know is that it was perhaps one of the first pieces of architecture built primarily for its own image.

The wrought iron icon went up just as a new technology—photography—was on the up and up, too. And with it came postcards. Once completed, tourists could send photos of the vistas bestowed from la Tour Eiffel’s height, or of views of it from the ground to friends and family.

Today, postcards have been replaced by the smartphone, but the impact is essentially the same. We all take the same photo of the same views and send it to our online acquaintances, letting them know where we are.

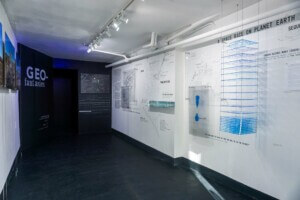

This phenomenon is explored more deeply in Photo City: How Images Shape the Urban World, now on view at the V&A Dundee.

The Kengo Kuma–designed museum is an apt location for the exhibition’s first outing. The sculptural $100 million museum’s cascading concrete is primed for the camera lenses of those who visit. The museum also takes center stage within Sohei Nishino’s Diorama Map, Dundee—a photographic collage of the city specially commissioned for the exhibition. Though Nishino’s photos capture a wide area, the Japanese artist focuses on details and people. “This wasn’t like cities I’d captured previously,” he told AN. “Before the coming I had no prior knowledge of Dundee. I spoke to people every day [over six weeks] to get a deeply personal perspective. It’s a social portrait of the city.”

Besides Nishino’s work, Photo City is a compilation of photographs, films, and imagery from the V&A’s vast archive that thrusts visitors into the history of the camera—and specifically how it coincided with the boom of cities. We are introduced to Nadar, an avid aerial French balloonist hell-bent on using hot air to capture the city from a new perspective. Though the first genuine aerial photograph was in fact taken in Boston, by James Wallace Black in 1860.

But just as the camera was used to document urban expansion and the creation of new cities, it has also been a means to destroy them. Almost immediately this novel technique of surveillance was weaponized by militaries to aid war efforts. A bit later, aerial photography was adopted by planners to plot urban development more formally—and exclusively—based on evidence and perspectives captured from above.

While Google Street View and camera phones have documented much of the Western world today, it was Cairo that was one of the most photographed cities in the 19th century, chiefly due to the cultural, military, and financial interests of Europe.

But while the city of Cairo was the subject back then, its individual inhabitants were not. Street life was difficult to capture due to the long exposure times demanded by early camera technology. Photographs of Cairo on display in Photo City show crowds that remain a blur.

That all changed later as cameras became more adept at capturing movement. Street photography emerged as a means of social commentary, and suddenly the city and the lives of its people came into focus. Some of the best street photographers including Henri Cartier Bresson, Berenice Abbott, and Paul Strand are all on show, brilliantly capturing city life, within which New York, and all its glamour and grit, features heavily.

There’s a distinct architectural focus here, too, with the work of the Smithsons as well Denise Scott Brown and Bob Venturi highlighted as a way of showing how street photography—connecting people to place—has inspired design methodologies.

Surveillance and the notion of city as a stage set is another undercurrent throughout the show. Who is photographing who and why? The digital frontier of capturing cities is the exhibition’s curtain call. As early aerial photographers snapped oblique views of ground below, they omitted the horizon line, causing cities to appear limitless. This, it turns out, is also the view favored by game developers who hint at this limitless-ness in the virtual realm.

Photo City, an exhibition that satisfies a nostalgic thirst for brilliant street photography and surprises with some uncomfortable truths, ends with Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982)—perhaps one of the most iconic pieces of moving picture used to document urban life. Alongside it, Irish artist Alan Butler has recreated it using a hacked version of Grand Theft Auto—the infamous video game which was born right here in Dundee.

Jason Sayer is a writer and lecturer who works for Architecture Today in London.