Geo-Fantasies: A Space Race on Planet Earth

Citygroup

104b Forsyth Street

New York

Through June 16

Carbon capture is often heralded as the future of climate change technology. It sounds like a simple solution to the global emission problem: Carbon is captured from the emission point and stored geologically, preventing further greenhouse gas effects. But how might the transportation process from capture to sequestration site impact the very environment the industry claims to protect? What risks could carbon capture impose upon the land and soil that this infrastructure occupies?

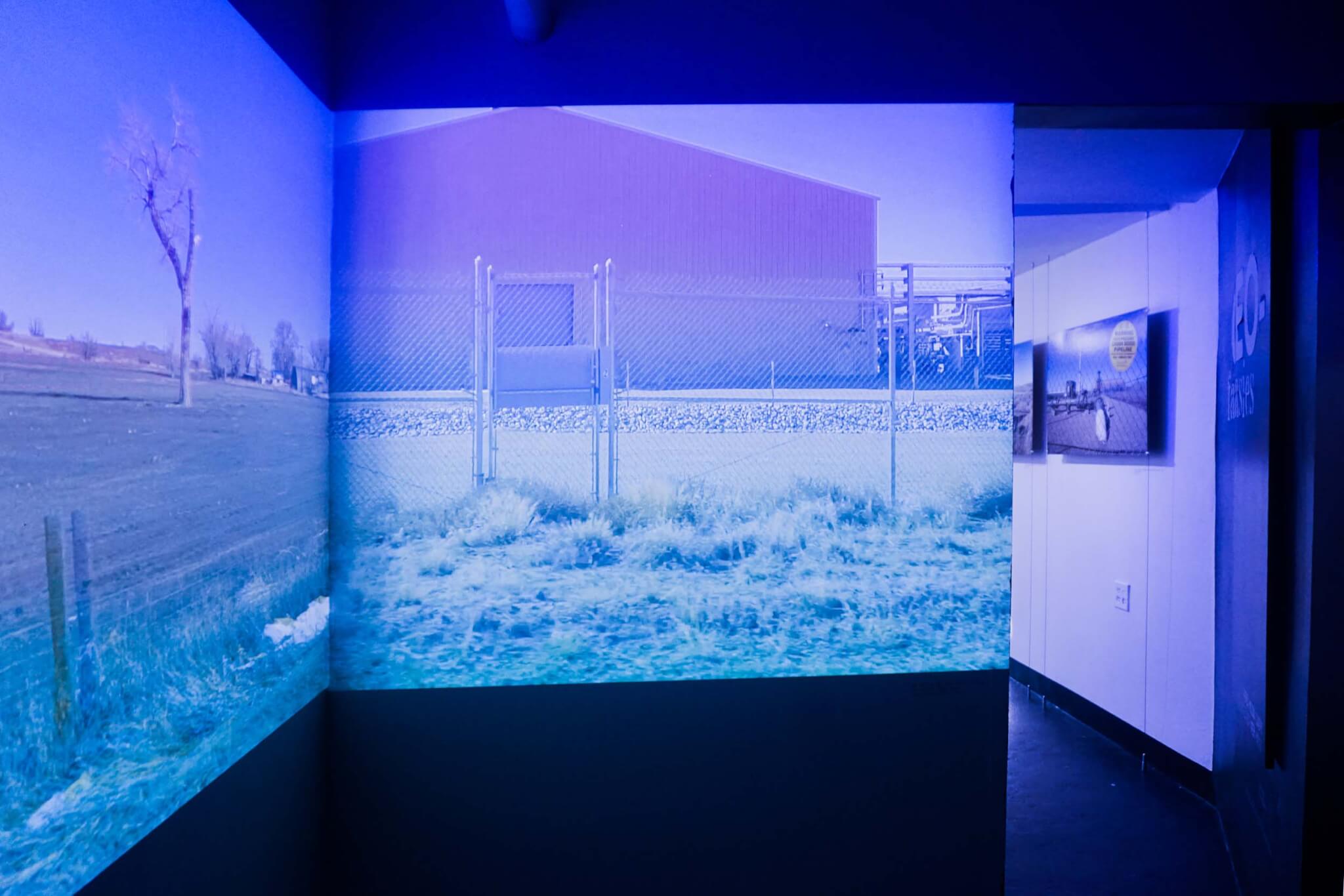

A new exhibition turns a critical eye on the carbon capture and storage industry at New York’s Citygroup, a collective space for “the production of theory and strategy that supports an alternative approach to architecture.” Through a diverse array of materials—photographs, maps, drawings, documents, a two-channel video piece, and an installation—Geo-Fantasies: A Space Race on Planet Earth interrogates the spatial practices at work with carbon capture initiatives in Wyoming and Montana.

Curated by architectural researcher Andrea Molina Cuadro in collaboration with designer Reem Yassin, Geo-Fantasies draws from Molina Cuadro’s research trip to the western U.S., painting a comprehensive portrait of the region’s carbon capture facilities. Not unlike nuclear waste facilities of the Cold War era, the vast Western territory and its arid, desert landscape is thought of as a safe and secluded dumping ground for hazardous infrastructure like transportation pipelines, refinery plants, and the remains of old oil fields. Originally conceived of as a research paper, Molina Cuadro expanded her work beyond the written word in an attempt to better capture the scale of the industry and depict the spatial appropriation at stake. “It displays the controversy between the climate reparations rubric and the massive undertaking and deployment of infrastructure,” she told AN.

Geo-Fantasies transforms Citygroup’s gallery space into a canvas. By reconstructing maps of the Shute Creek gas plant in southwest Wyoming to the Bell Creek oil field in Montana, the visuals trace carbon’s path from capture site to sequestration location. Transparent blueprints of the gas plant and refinery overlay the maps, further emphasizing the extent to which the carbon capture industry is layered with environmental saviorism to conceal underlying issues.

Indeed, layering is a consistent theme. The exhibition culminates with Pore Space, an immersive installation comprised of 22 stacked pieces of laser-cut acrylic squares filled with blue-pigmented epoxy resin. Pore space, or the empty space between particles of sand and sediment, are the miniscule voids where carbon can be stored underground. The carbon sequestration industry relies on this, injecting carbon into the ground and filling the void-space. The entire mass hangs from the ceiling. “What is this new resource that the industry is creating? It’s something that didn’t exist for capitalism before. These pore spaces underground had no value,” Molina Cuadro said.

Ultimately all exhibition materials point to this creation of viable economic value where there was none before. This new, opaque industry literally imposes value on negative space. Not to mention that the companies that own this carbon capture infrastructure are the very same ones that spew carbon into the atmosphere: ExxonMobil and its subsidiary Denbury Carbon Solutions.

With the evidence laid out before you, the exhibition asks the viewer to look beyond the perceived environmental benefits of carbon capture and consider the ramifications: Do we really need more land co-opted by infrastructure serving oil companies? Perhaps we could funnel more resources toward the trees instead.

Amelia Langas is a freelance art and culture writer based in Brooklyn.