As far back as the 13th century, when students at the Sorbonne got into armed brawls with Parisian tavern keepers, the town-and-gown relationship has been a fraught one. Treading on issues of class and culture, the tension between educational institutions and the communities that surround them is often exacerbated by attempts at keeping the one segregated from the other: Walling up the groves of academe only irritates the neighbors, and worse, it blocks out the light.

But in Waterville, Maine (population 16,000), some of those walls are coming down. On my recent visit, major changes appeared to be afoot—in a gaggle of new student-friendly restaurants and a bar, a new bookstore, and in a couple of major new buildings dotting the old downtown streetscape. “It’s enlightened self-interest,” said David Greene, president of Colby College. Since assuming the post in 2014, Greene has been busy finding new, resourceful ways of making his 211-year-old liberal arts program an integral part of its hometown’s future. His most recent venture at Colby is a new facility for a local arts group called Waterville Creates: The Paul J. Schupf Art Center was recently completed by New York–based architect Susan T. Rodriguez Architecture and Design (STR), and it’s a multivenue cultural hub smack in the middle of Waterville’s Main Street.

“We’ve had an incredible array of arts assets here for years,” said Shannon Haines, president and CEO of Waterville Creates. First launched a decade ago, Haines’s organization is a composite of several local institutions: the Ticonic Gallery + Studios, a grassroots art-making space; the Maine Film Center; and the Waterville Opera House, a fixture of the town for over a century. With Greene and Colby playing matchmaker, longtime college donor Paul J. Schupf left his estate to Colby for the purpose of creating an arts center in downtown Waterville. When Maine-based OPAL Architecture heard about the project, it asked STR’s founder, Susan T. Rodriguez, to partner in the interview process. Together, they won the commission with a design solid and simple enough to fit in on old-fashioned Main Street, yet flexible enough to accommodate not just Waterville Creates but a new outpost for the Colby College Museum of Art’s impressive collection. “It really is a collaborative effort between Colby and the local arts community,” said Rodriguez, herself a seasonal Mainer for many years.

Colby’s physical presence downtown represents a rapprochement of sorts between city and school. As David Greene notes, Schupf Arts has roots that “go back to the history of Colby and Waterville.” The college was originally located in the town proper before moving in 1929 to its current digs to the west, about a ten-minute drive away (on grounds deeded by the town, no less). Following its departure, Waterville persevered, but the region’s declining industrial sector slowly caught up with it, leaving behind vast, empty mills and a sense that the town’s best years were behind it. “They’ve seen some hard times,” Rodriguez said—though times have plainly been changing of late. Walking down Main Street, I passed a new parent-friendly hotel, a college dorm, and a bus running between downtown and the main campus. All are evidence of Colby’s increasing reinvestment efforts, with the Schupf Arts now the jewel in the crown.

To place a new arts center right at the center of the town, rather than on Colby’s campus, Rodriguez and her collaborators—including architects of record OPAL Architecture—had to contend with a delicate urban condition. The site is fronted on one side by the village green (a classic New England feature) and on the other by city hall, which doubles as the opera house (another staple of small towns in the region and elsewhere). The former occupant of the corner property was a somewhat awkward 1930s-with-additions pseudo-Georgian structure. Waterville Creates had kept offices in the building for years, but it was totally unsuited to the art group’s needs. “It was impenetrable,” said Haines. “There were almost no windows.” After some attempts to preserve it, it was decided the old would have to make way for the new.

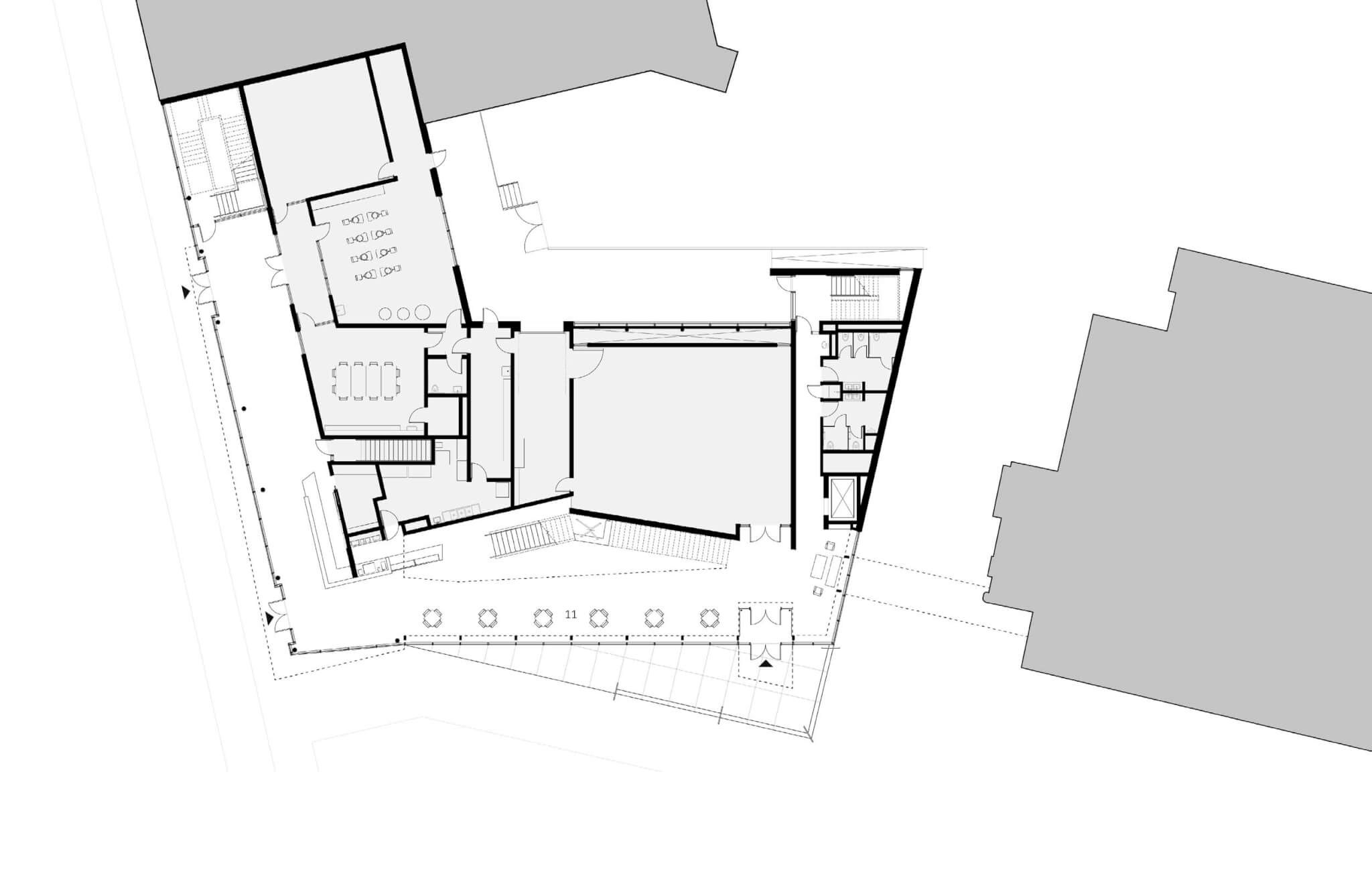

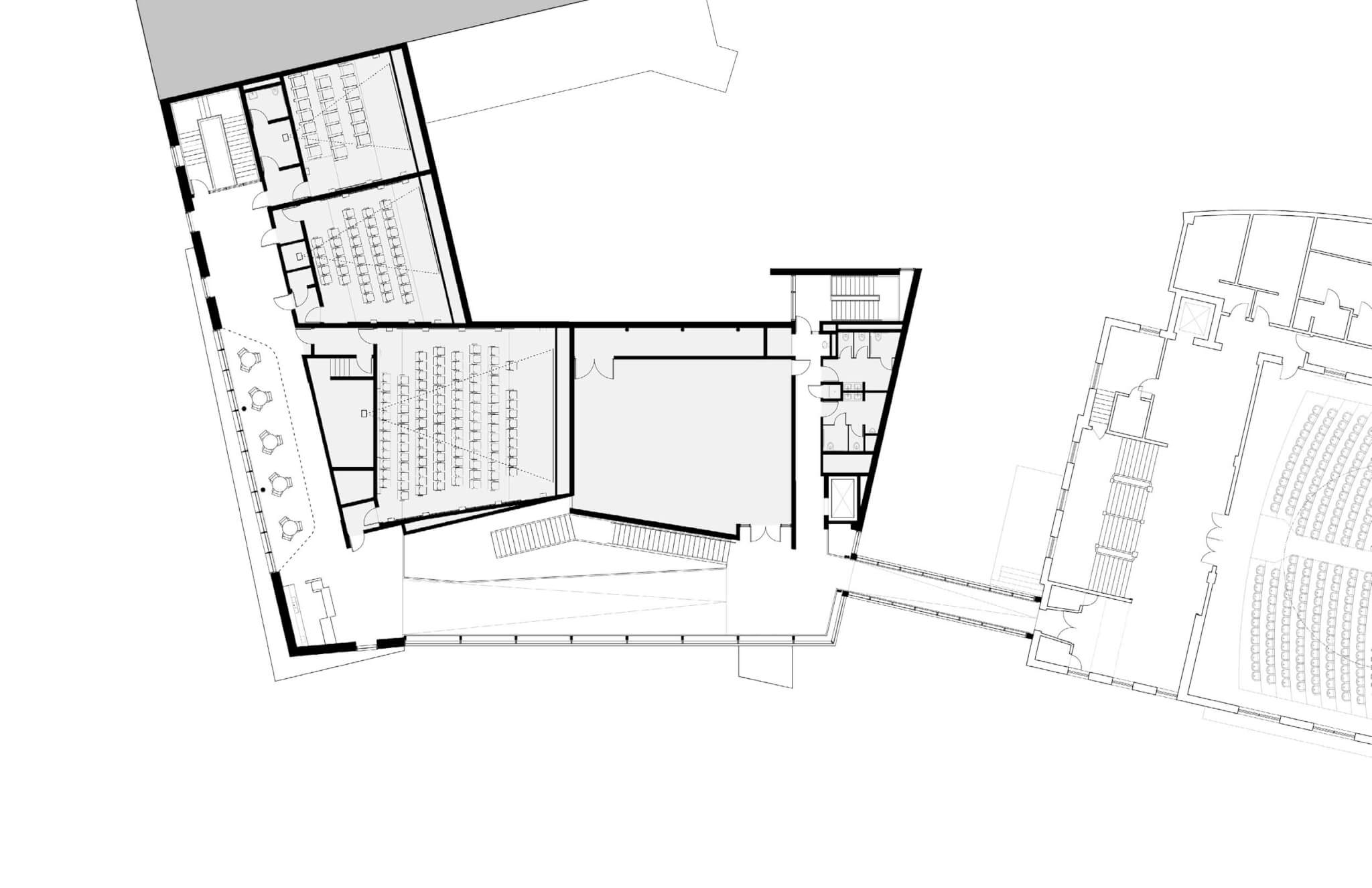

That move opened the door for Rodriguez and company to—well, open up the door. “It was so important for [Schupf Arts] to have a sense of generosity,” said the architect. “We wanted this to be like a living room for downtown.” With a fully glazed facade looking over the village green, and a strongly articulated Main Street entry, the new design combines a feeling of freshness and openness with a simple material palette and modest scale. Where the old building effectively masked city hall from the street, the new one reestablishes the visual connection from west to east. This was an important prelude to STR’s chief logistical coup: Coming through the doors on Main, visitors can cross the glazed southern lobby and proceed up a set of stairs to a skywalk that leads directly into the opera house. A physical expression of Waterville Creates’s multipart organizational structure, that link is complemented by a plan that gives each program its own discrete space, with movie screens upstairs, the community studio and gallery at street level, and the Colby College Museum of Art’s satellite toward the rear.

On a cold winter day, the building certainly seemed to be living up to STR’s vision of a warm, collective gathering space, as a local weavers’ group gathered with their spinning wheels near the theater’s concession stand, home-baked goodies filling the space with a distinctly cozy aroma. But the space also draws Colbians off campus: “You see college students here all the time doing homework or just relaxing,” said Haines. And that’s exactly what their school’s president was hoping for. “Students today can choose from a lot of exciting places,” president Greene said. “This is making a huge difference in attracting people to Central Maine.”

Ian Volner is a Bronx-based writer covering architecture, design, and urbanism.