The allure of a routine is catnip for the human condition. But when a schedule becomes a work-a-day gig beset by what some may call a “9-5 mentality,” the drudgery slaps not of commitment but mechanization. By now we all know that in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic many workers—notably, white-collar and creative-class individuals—are reevaluating their relationship to office work. (And, correspondingly, the owners of office buildings are reeling with the prospect of their suites staying empty for good.) In the 21st century, the future of work remains an evergreen topic which has inspired much head-scratching and countless prompts for architecture studios.

For so long, work has been an easy way to check the “fulfillment and purpose” box on the survey of life. But this era has come to a close. Where does that leave the office?

Knowledge workers and the “creative class” are products of the “gig economy” that emerged after the 2008 fiscal crisis. The promise of being able to work anytime and anywhere led many mostly younger and well-educated adults to sacrifice job security for the promises of greater freedoms and non-traditional schedules. But a few years on, the success of the gig economy model—which rests on the shoulders of precarious workers with difficult relationships to health insurance and looming doubts of permanent rentership—has also made its way into what we used to think of as more traditionally stable jobs, even career paths.

Pop culture offers regular takes on changes to the way we work by taking up the office as not only a set but an aesthetic.

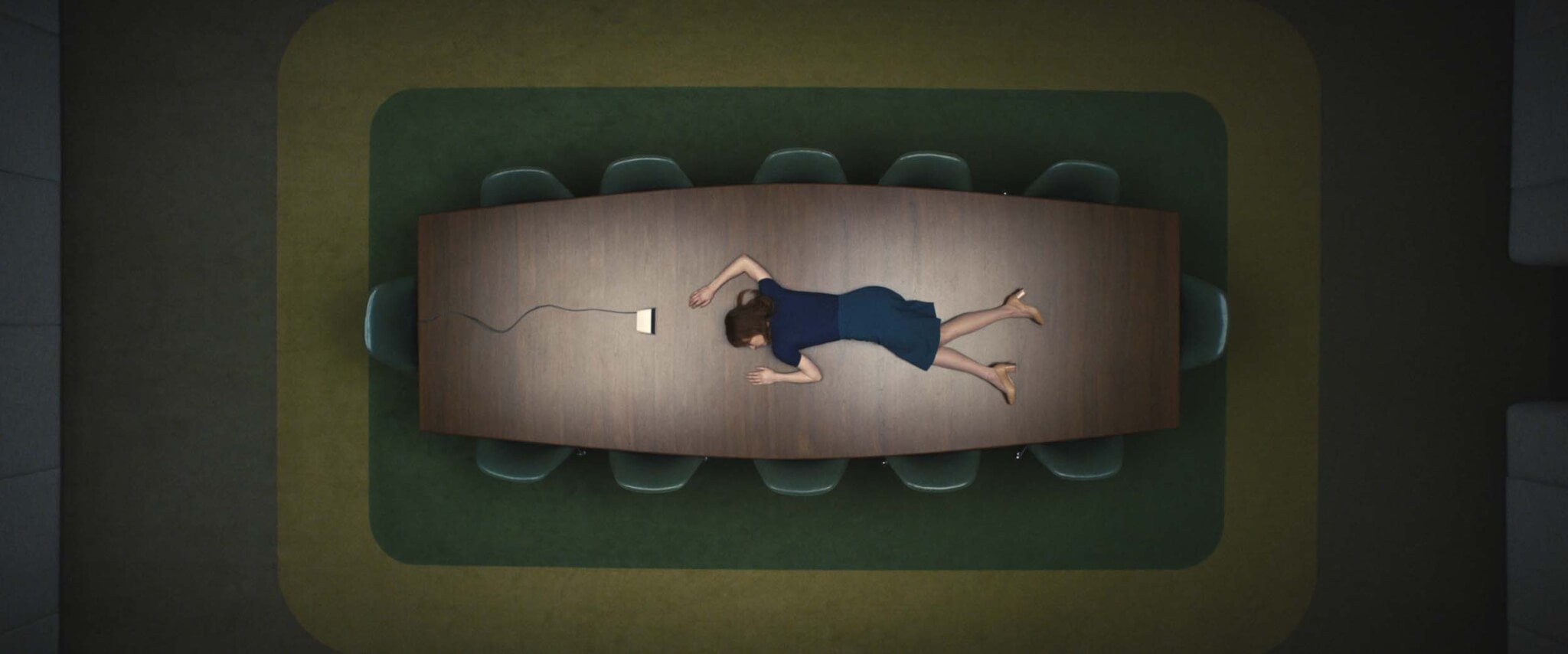

Perhaps the most successful recent example was the 2021 debut season of Severance. For architects and design heads, the show’s setting within the modernist Bell Labs—alternately a masterpiece or nightmare, depending on your interpretation—was a compelling hook. The facility, designed by Eero Saarinen and completed in 1962, was an early successful version of the suburban office park, a midcentury trend that “liberated” white collar workers from the crime and filth of the city in exchange for the auto paradise and manicured lawns of isolated labor parks. However, the sleek, totalizing design of Severance’s fictional corporation, Lumon Industries, takes the all-inclusive trope of the era’s architecture a step further.

The show flips the relationship between home and work on its head, offering work as the place of life and fulfillment and home as the liminal in-between. The show follows Mark S., a hard-drinking, visibly depressed widow who is clearly going through something. He leaves his banal (yet ostensibly “modern”) townhouse, squeezes into a compact car, and arrives at Lumon, where he neuroscientifically checks out for the day as a “severed” employee.

At Lumon, tactics that have been used throughout history for placating and isolating workers are on full display: Teams are limited to the smallest numbers to stave off insurrection, and sectors are physically isolated from one another through a dizzying maze of corridors. The corporation’s founder is worshiped in a religious or cult-like manner, inciting loyalty through Machiavellian means. But the show’s production takes care to evidence Lumon’s manipulation through small-scale incentives like branded tchotchkes and dance parties to briefly escape from the monotony of macrodata refinement.

Severance was a hit, but it was also a reprise of an old idea. Severance stars Adam Scott as Mark S. and is directed by Ben Stiller, the same main character/director duo behind the 2013 film The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. The similarities between these two projects demonstrate that Stiller has been stuck on the theatricality of the corporate for at least a decade. Both productions use iconic midcentury works of architecture for their scene-setting: Mark S. toils at Bell Labs while Walter Mitty starts his commute from the aboveground 125th Street 1 train station before descending straight into the heart of Midtown Manhattan to the Time & Life building’s POPS-able fountain and raised plinth.

The office architecture responds to the two characters’ problems. The Time & Life building is a vertical monolith and Bell Labs is a horizontal mat building, both interiors are recreated via stage sets to realize nearly identical versions of anonymous, generic space. Endless miles of white corridors with fluorescent-lined suspended ceilings lead both Mitty and Mark S. to their comfortable, bland jobs. For each, the architecture of the workplace is staged as a coping mechanism. Their routines are a form of escape through anonymity instead of the heroic attitude adopted by the architecture’s exterior expressions. Inside, both characters literally work in the basement, have little to no contact with those “upstairs,” and commiserate with coworkers who share some resemblance, at least in attitude.

But as the narrative arcs bend, each character is slowly revealed to be essential in the same realization that beset many during the pandemic: Labor becomes visible when it becomes precarious. In corporate power structures, there’s hardly any room at the top, and the pyramid’s foundation is made up of workers hidden from view; they may thrive in the catacombs of the modern office, but their strength is in their numbers.

The history of the late-20th-century office spaces like these is the subject of The Office of Good Intentions. Human(s) Work, written by Florian Idenburg and LeeAnn Suen and published last year by TASCHEN. The selected case study offices are striking both for their enduring relevance but also for their relative obscurity. The chain of events revisits how the Bürolandschaft design concept of 1950s Germany made way for the Herman Miller Action Office blueprint, which was followed by the cubicle-scape we all still associate with corporate America.

Despite the activity portrayed in photographic sequences shot by Iwan Baan, one wonders how much creativity is really going on in these spaces. Are these spaces of motivation and innovation? Or are they populated by workers who, like Mark S. and Mitty, keep their head down and cross off the days until Friday on their wall calendar? Mark S., Mitty, and others are imbued with Main Character energy not by the design of their (fake) offices, but by the oppressive changes that higher-ups brought onto a somnambulant workforce. Mark S. watched his company psychologically toy with coworkers to the degree that one eventually attempts suicide, while Mitty felt the pressure to attempt extraordinary measures just to avoid being fired casually; neither his tenure nor loyalty could save him.

Midcentury “corporate” space is a familiar stereotype that haunts the contemporary office like a ghost of the prior Mad Men era, where unquestioning loyalty mixed with deviance was not only the norm but glamorous, even sociable. Today’s company managers are trying desperately to bring this attitude back, or at least to install a similar sense of surveillance in remote workers through software monitoring or internal social platforms like Slack.

A more extreme and contemporary version of toxic work environments is on full display in HBO’s Succession. This story of the 1 percent of the 1 percent also folds in the absurdities of office culture as part of its generational struggle. The allure of fantastic wealth makes us all collectively curse when one Roy sibling is threatened with “flying commercial,” and paper shredding plays a central role in season 1’s plot. Success is displayed through influence, wit, and personal branding. The decentralized lives of the Roy family responds to a cultural desire for the executive life, with the freedom to conduct business anytime, anywhere—from a yacht, secluded mountain retreat, or Waystar Royco’s skyscraper HQ in Manhattan’s FiDi. In seasons 1 and 2, it was shot in two World Trade Center buildings (4 WTC by Fumihiko Maki and 7 WTC by SOM), while in season 3 they shift to 28 Liberty, designed by Gordon Bunshaft.

Lately, office designs trend residential. During the pandemic, demand for the ideal home office skyrocketed. Instagram feeds, lifestyle magazines, and addictive shelter-themed videos (like the AD Open Door YouTube series) show us the light-filled homes and studios of bicoastal creatives whose life and work have blended beautifully. The office becomes a stage for big personalities, the intrigue of object curation, and the material comforts of home-like environments. These qualities were anticipated by West Coast offices like that of Chiat/Day, designed by Gehry Partners to be chill and cool. The home version—distilled down to a single laptop or app—are places where work becomes more tolerable by being compartmentalized. Work is what temporally flows around our appointments, errands, lunches, and walks. The promise of work-life balance often loses its hyphen and slips into work life.

In a moment where the architecture industry is finally waking up to the lived realities of unfair wages, intra-industry nepo babies, and accumulations of unpaid overtime, many refuse to tolerate the status quo. The Architecture Lobby and Architecture Workers United are first steps toward making the profession more humane, communal, and accessible. If Mark S. is able to organize his workplace and find his way out of an opaque regime simply by mapping his office on the back of a photograph, surely we can seek to understand the inner workings of the workplace beyond the shiny veneer of a rendering or unlimited kombucha on tap.

Idenburg and Suen’s research and the set of mentioned media serve up studies of what the office has been. What will it become? One popular solution is to convert them to housing, as many office buildings—amply windowed and centrally located in desirable neighborhoods—currently sit vacant. But what kind of housing will be realized? Rather than shoebox one-bedrooms, towers could be converted into collective live-work spaces for a new generation of urban workers, designed to blend rather than sever connections among parts of an occupant’s life.

The office, thoroughly mythologized in American media, stands to be reimagined for today’s workers. Rather than just installing new bosses in existing corner-office suites, the huge floor plates could be rearranged to bring people together rather than keeping them apart.

Emily Conklin is an architecture critic and historian currently inspired by her nostalgia for a 19th-floor Chicago apartment. Her writing has appeared in New York Review of Architecture, Surface, and Platform Space, among other publications, and on her Substack Design Trich.