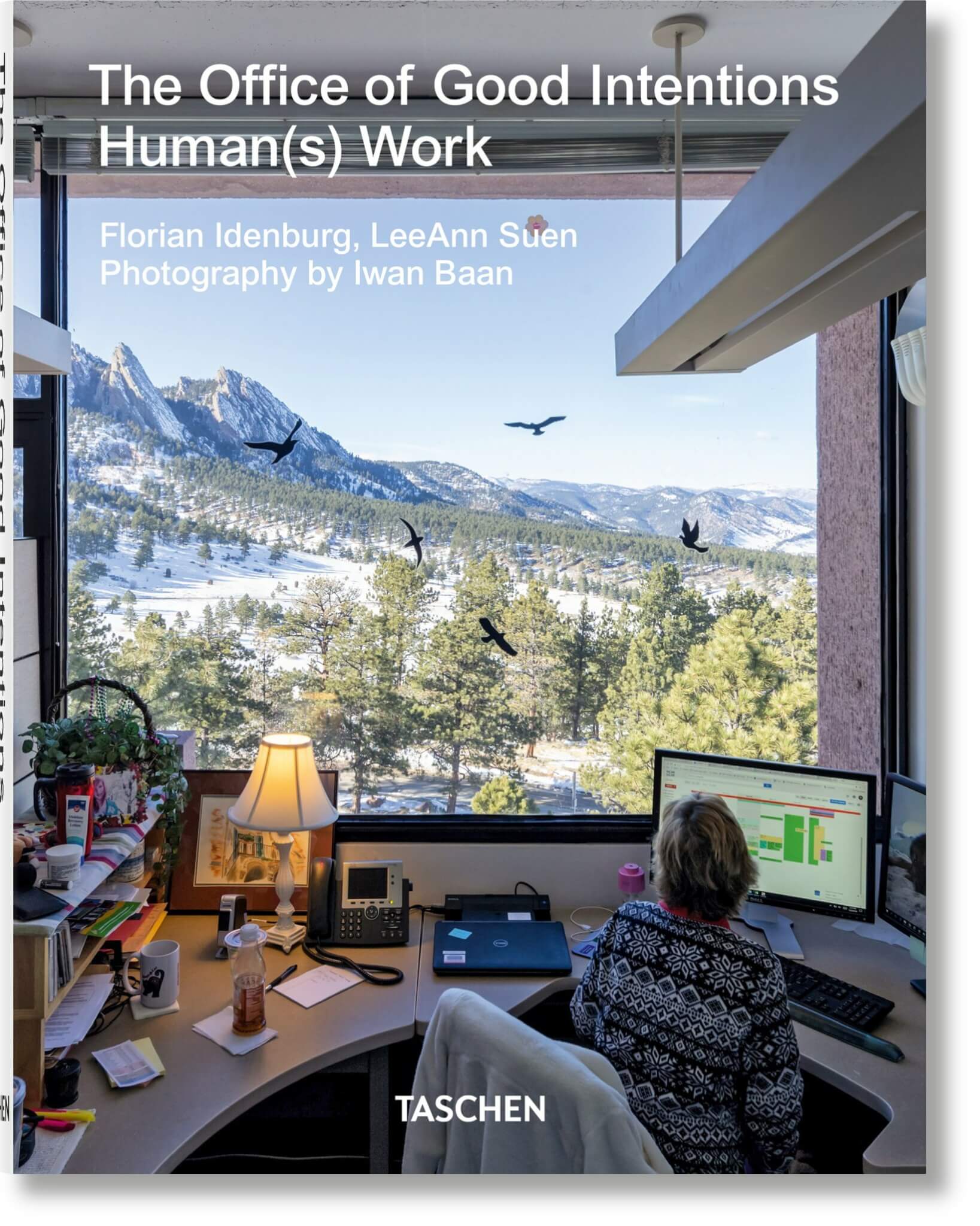

The office is one of those spatial types that offer perennially productive problems for designers. The Office of Good Intentions says it all in its title: Drawing attention to “good intentions” is necessary only when they don’t come to fruition. Although the book, written by Florian Idenburg and LeeAnn Suen, sets its primal scene in the 1960s, the office’s problem is as old as the office itself. The word bureaucrat was coined following the French Revolution to identify the regressive forces that were supposedly holding society back from its true potential, an impression captured by Franz Kafka in his novel The Castle. (The author also worked as a law clerk.) Since then, the office has been synonymous with alienated labor of the white-collar variety.

Wisely, the authors of The Office of Good Intentions do not purport to offer a solution to our collective office woes. Instead, Idenburg and Suen have put together an expansive survey of attempts to bring technology, space, and social organization into harmonious alignment, with varying degrees of more-or-less short-lived success. The volume begins by recalling the dream of human-machine symbiosis (read: office worker and computer)—a fantasy that many, like MIT researcher Joseph Licklider (the subject of the book’s opening episode), expected would be realized around, say, 1970. It becomes clear in the following pages that technology intensifies the office problem at least as frequently as it furnishes solutions. Licklider was involved in the development of ARPANET, the precursor to the internet, which has become the one nefarious technology that now rules them all. Prefiguring this development, Stanford researcher Douglas Engelbart delivered “the mother of all technology demonstrations” in 1968, showcasing how interconnected devices could facilitate collaborative remote work and teleconferencing. We have seen how this story unfolds during our pandemic years of experimentation with remote work: It’s sometimes a relaxed and streamlined work session at the beach, but more often, it’s surveillance software virtually chaining workers to desks in makeshift—and oxymoronic—home offices.

A central theme of Idenburg and Suen’s book is the recurring attempts to make offices paperless. The first case study focuses on the evolution of advertising guru Jay Chiat’s “vision of a workplace for digital nomads.” It begins with Frank Gehry’s iconic Chiat\Day headquarters (1991) in Venice, California, where workers enter beneath a giant pair of binoculars (designed by Claes Oldenburg) into a freewheeling “carnival of charisma,” which the authors astutely link to painter Robert Rauschenberg’s Combine series. At the company’s New York office, designed in 1994 by Gaetano Pesce, employees were required to find a new workplace every day after checking out a fresh laptop through a window surrounded by alluring red lips. It didn’t work out: “In New York, employees simply stopped coming into the office, or else camped out in walled conference rooms,” readers learn. “In Los Angeles, workers used the trunks of their cars as filing cabinets and stopped returning their portable phones and PowerBooks.” After a 1995 merger with TBWA Worldwide to create TBWA\Chiat\Day, the firm’s newest office, designed by Clive Wilkinson Architects in 1998, dropped the earlier fun-house atmosphere in favor of office urbanism, complete with streets, neighborhoods, and buildings in the idiom of stacked shipping containers inside a giant warehouse-like space. The case study is rounded out by comments on Google and Facebook offices, which embrace the freewheeling aesthetics that Chiat\Day pioneered. If there is a lesson to be learned, it is that paperwork is part of the DNA of the office. Max Weber said as much in his sociology of bureaucracy a century ago. To paraphrase: Bureaucracy is when workers in an office use equipment to shuffle paperwork.

Read more on aninteriormag.com.