An Atlas of Es Devlin

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

2 East 91st Street, New York

Through August 11, 2024

The studio visit is one of the perks of being a museum curator. It’s an opportunity to see what’s preoccupying an artist—the books they’re reading, the problems they’re sketching out, the odds and ends that they’ve picked up. It offers a less-polished view into how a creative figure thinks, with the false starts and dead ends the public never sees displayed alongside recognizable successes. And because of this, it potentially reveals more honesty about who the artist is. “It’s a curator’s happy place to be surrounded by the aura of objects,” said Andrea Lipps, one of the organizers of An Atlas of Es Devlin, on view at the Cooper Hewitt, which centers on the groundbreaking work of the British set designer. “There’s an immediacy to drawings, sketches, and things that the artist’s hand has touched.”

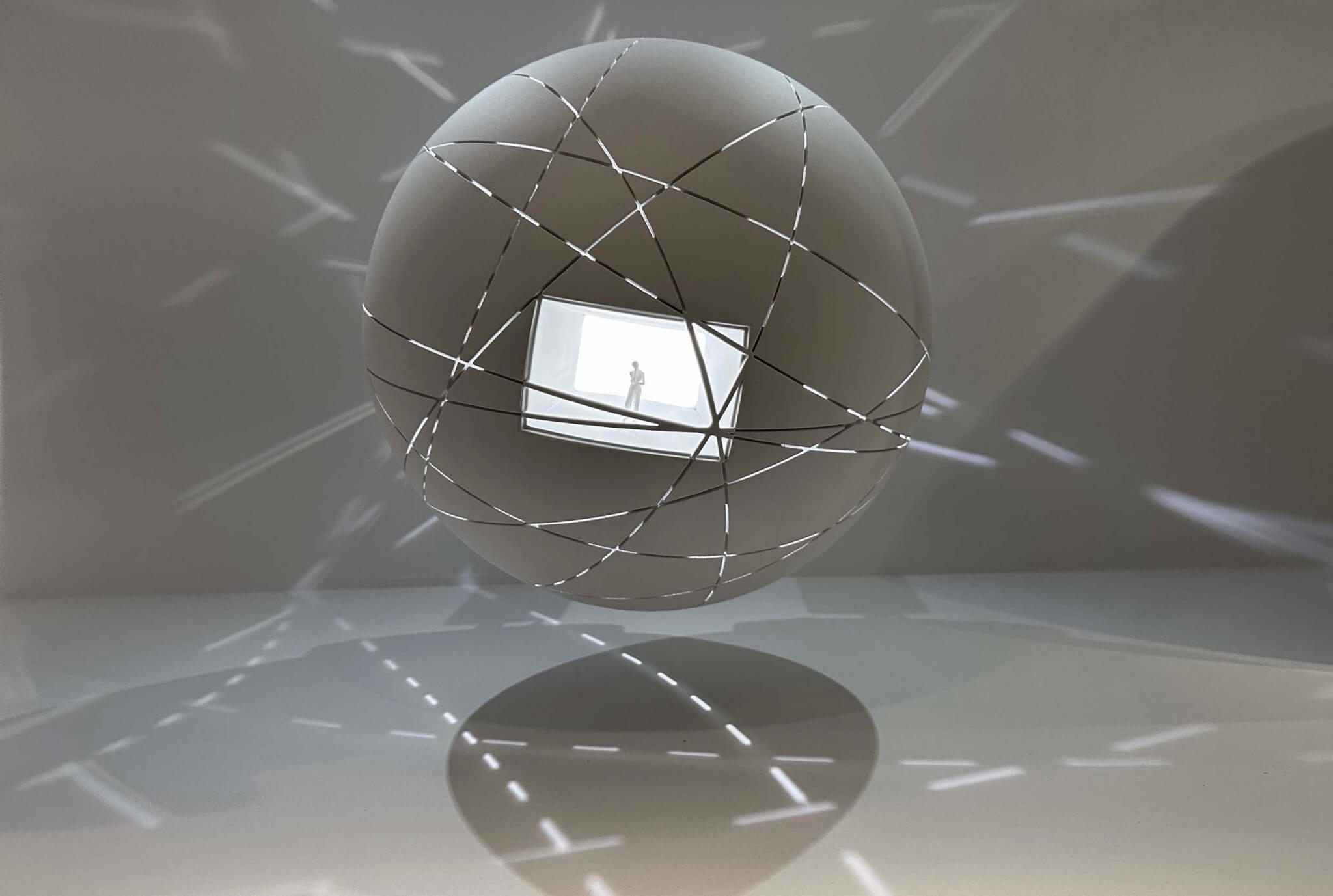

Even though Devlin, now 52, isn’t a household name, her clients certainly are: Beyoncé, Adele, Rihanna … the list goes on. Though she is one of the most widely seen artists of her generation, the Cooper Hewitt retrospective is one of the rare times Devlin has been recognized as the main character. Since opening her studio nearly 30 years ago, she has designed over 400 projects, spanning stages for stadium tours, a closing ceremony for the Olympics, Super Bowl halftime performances, theatrical festivals, and runway shows. As Devlin described in the 2017 Netflix series Abstract: The Art of Design, she feels an innate drive to fill the world with art. This includes monumentally scaled sculptures (like a 30-foot-wide model of New York City’s skyline twisted into an egg-shaped orb); building kinetic sets, like her Tony-winning concept for the play The Lehman Trilogy, which consisted of a rotating modernist glass office; and exploring new technology, like projections and generative AI. Her public installations have graced Trafalgar Square and Lincoln Center. “She’s always creating the scaffolding for others to perform on and to tell their stories,” Lipps said, “and this is the very first time that she was creating it for herself.”

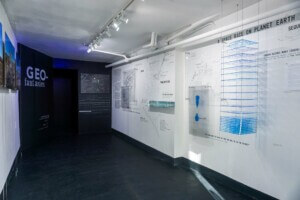

It’s fitting, then, that the prelude to the exhibition takes place in a replica of Devlin’s studio. The room is dimly lit, all white, and wrapped in floor-to-ceiling bookshelves holding paper models, storage boxes, and trinkets. There’s a wide desk in the center of the space strewn with eraser shavings, cups brimming with rulers and pencils, blank notebooks, and manuscripts. Soon, images of Devlin’s notes and drawings are projected on the desk and a video begins to play on a blank wall in front of it. We see Devlin’s own hands drawing and cutting paper as she narrates, in a soothing and breathy voice, the story of who she is and how she thinks. As the film concludes, the blank wall reveals itself to be a door that slowly opens to the exhibition beyond it.

“There was very much a desire for the exhibition to feel intimate, to feel like you exactly have stepped into this space of the artist, that you are able to catch a glimpse of things beyond the finished glossy product,” Lipps said. “You get to see some of the messiness of it.”

While Devlin’s medium might be sets, she is foremost a designer of experiences. The results of her works are a feeling, and she uses images, architecture, light, and sound to evoke it. She is known for creating arena spectacles (her latest is U2’s residency at the Las Vegas Sphere), but her interest in designing experiences started at a much more intimate scale.

Devlin recalls walking down the corridor of a music school as a child (she studied violin for a little bit) and hearing snippets of performers playing Bach, Led Zeppelin, and Miles Davis through the glass doors of practice rooms. “Fragments of music, light, and atmosphere coalesced into something new and unnamable,” she wrote in a catalog accompanying the exhibition. She now sees her entire career as an extension of that corridor.

What Devlin is describing in her childhood memory is awe. And that’s what I felt the first time I knowingly experienced one of her installations, the 2016 Mirror Maze. It was a series of rooms that included a seemingly endless labyrinth of reflections bouncing down and around a corridor bathed entirely in red light and perfumed with Chanel fragrance. A film was projected onto a 360-degree screen set over a reflecting pool. While many of us outgrow a sense of wonder with the world, or find it harder to find as we age, Devlin has been able to harness this way of seeing and invites us to experience it with her.

Like all of Cooper Hewitt’s exhibitions, An Atlas of Es Devlin is intended for a wide audience, from school groups who are coming to the museum for a field trip to design professionals who are eager to learn more about their peers’ craft. Because of this, the exhibition operates on multiple levels: It’s a reacquaintance to Devlin for people who may have experienced her work without knowing it, an introduction to the genre of design for live performance, and a look at artistic process. But what I found to be most revealing was the design of the exhibition itself, which she personally created for the museum.

The specific challenge of exhibiting spatial design compared to more traditional mediums like painting or sculpture or film is that what someone sees in a gallery is almost always a translation, not the real “thing,” or artifact. We gaze at the scale model, read the book, and glance at photographs to approximate what it’s like to be within the space that cannot be there. The inherent ephemerality of Devlin’s work is an added layer to the challenge of exhibiting it. As Devlin said in the exhibition’s opening film, “Every audience is a temporary society that departs a performance in an altered state, the architecture of their mind redrawn.” Once the show is over, the stage is discarded. What’s left is the impact of being there.

However, because Devlin’s work is so experiential, the exhibition of her work is remarkably successful. While it’s impossible to re-create the 60-foot-tall rotating cubic screens she specified for Beyoncé’s Formation tour or the 80-foot-tall hands holding a deck of cards she created for the Bregenz Festival’s production of Carmen, we see mirrors, projections, and experiments with scale in the gallery. At the heart of her designs is the metaphor of a “memory palace:” a technique for recollection that argues ideas are best remembered when they are located in space. All her designs are environments that are physical analogues for the content of the performances that happen within them. As I walked through An Atlas of Es Devlin, I felt as though I were a voyeur in Devlin’s own memory palace, a participant in an immersive performance of her persona as a creative visionary.

The exhibition is an archive of more than three decades of Devlin’s creative output. The descriptions accompanying the sketchbooks and presentation models are written in first person, imparting a deeper sense of intimacy with the work. Devlin explained how her first design for a concert was in response to being bored. She shared many anecdotes, like when Lady Gaga’s feedback on a concept was “Now vomit on it,” leading her to source junk from a dump to roughen it up. We get a sense of her wide-reaching references, from Japanese woodcuts for a U2 stage to Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis for the Weeknd’s After Hours til Dawn tour. Lipps said, “She has this ability, then, to really distill everything into a singular gesture or form or idea that can carry a performance through.”

The exhibition ends with three films that depart from Devlin’s work for the stage, turning to engage nature and the interconnectedness of our environment, as if to say the spectacle is all around us, not just in the orbit of the celebrities for whom she designs. Over the past ten years, Devlin has been producing installations that grapple with environmentalism, especially the loss of biodiversity. I wondered what she thought about her industry’s environmental impact, especially since it’s dependent on temporary structures and the carbon cost of air travel. Now that might get at the kind of messiness that reveals something.

Diana Budds is a New York–based writer and editor interested in how design reveals stories about history, culture, and policy.