Working on historic buildings often requires compromise. Many state historic preservation offices, landmark committees, and preservation organizations across the country skew conservative, even if they claim to begin with good intentions. The U.S. has seen so much of its historic fabric and natural areas lost to new and overdevelopment, from the much-maligned history of urban renewal schemes in post industrial cities to the suburban sprawl that has led to natural resource fragmentation and degradation. This push and pull, which takes cues from extreme examples like the demolition of Penn Station, often ensnares small-scale, well-intentioned projects in its wake.

The productive work of repurposing existing buildings that springs from this context is often some of the most beautiful, well-considered, and environmentally sensitive design emerging today. That exact push-pull is what Ann Arbor, Michigan–based architects PLY+ found grace within during the realization of the School at Marygrove, an experimental education project resulting from collaboration between the firm, Detroit Public Schools, and the University of Michigan School of Education. The adaptive reuse project revitalizes the long-abandoned, historic Immaculata building on the 53-acre campus of what was Marygrove College in northwest Detroit into a colorful and experientially ambitious P-20 program. The name might sound familiar: Beyond two renovated buildings, the complex also includes a new-construction Early Childhood Education Center designed by Marlon Blackwell Architects.

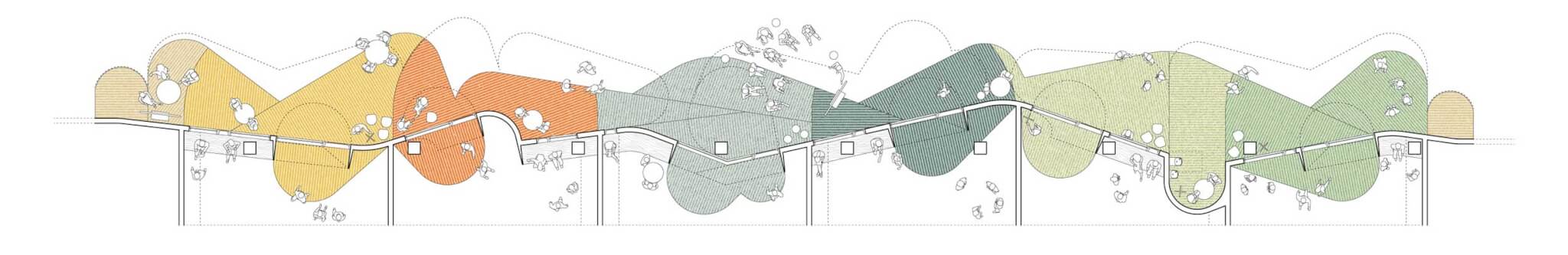

For PLY+ principal Jen Maigret, a generative constraint that emerged early in the schematic design phase was the school’s run-of-the-mill corridor. It looked exactly as you would imagine: a long, linoleum-lined hallway lined with metal lockers, animated by the sounds of rebellious slamming, metal bell clanging, and students pushing up against each other in an overcrowded, rushed environment. Maigret and her team originally saw ample opportunity to amend this age-old experience by reconfiguring the entire corridor, introducing sinuous walls sloping at soft angles to create corner nooks for informal gatherings and respite from the throngs at the center. However, when the very stereotypical double-loaded corridor was identified as “historically significant” to the Immaculata building—and therefore untouchable in terms of form—Maigret merely shifted gears.

Focusing less on the architectural form of the corridor and instead on the endless march of lockers, PLY+ reenvisioned the rows as syncopated clusters of “cubbies.” By losing the metal doors and instead opening the flanks up as recesses for small drawers, exposed coat hangers, and overhead bins, the cubbies not only effectively work as storage, but double as casual seating that naturally clusters small groups of students together in identifiable ways— just like her original goals for a more formally altered corridor. A theme of transparency begins to emerge; it plays well with the firm’s focus on materials and fabrication. The potentials of customized furnishings and novel, place-specific treatments take the project’s adaptive reuse constraints miles further than expected.

But the historic fabric can also yield unexpected wins. Vintage character and distinct geometries abound in Marygrove’s architecture, notably in what students now call the Media Room, which was formerly a chapel dating from the building’s stint in the 1980s as an all-girls Catholic high school. Located on an upper floor of the building, the room’s arched ceiling and raised pulpit were retained but remixed into an exciting multimedia room for younger students. Filled with flexible, curvilinear custom furnishings by PLY+ painted with pops of pastel color, the space encourages students to learn through interaction and play. Whether exploring technology, from recordings and video equipment, or physically designing their own learning space by moving furniture around like set pieces, children are supported in this space. They can then showcase new ideas or talents by literally putting on a show: The chapel’s old pulpit has transformed into a stage raised just slightly above the main floor, complete with sliding green curtain for theatrical effect.

“The media room differs from the library or reading rooms we have on the lower floors because it’s specifically designed for younger children,” PLY+ founder Craig Borum said. “It’s focused on the students who can’t yet read at high levels but are ready for alternative or emerging forms of visual media.” The chapel-turned-media room also solves another code-inflected issue with the historic fabric: Fire codes require that young children have their own modes of egress separate from older kids and adults because they are, of course, physically smaller and move slower. “The media room allows us to elevate space for younger students on the upper floors of the school without mixing that means of egress,” Borum explained.

After larger programmatic considerations were agreed upon and codes met, the team invested time in the details, right down to the hardware and colors selected for the experimental school’s fit-out. As part of PLY+’s commitment to wellness and sustainability, all the custom furnishings and selected finishes were natural. Plywood was used extensively for playful, curvilinear furnishings and a preference for hardwood flooring and tiles trumped the use of midcentury linoleum. Light fixtures were also chosen throughout to complement, rather than overwhelm or replace, natural light in all classroom spaces. Previously, the historic building had the classic midcentury treatment of dropped ceilings. What PLY+ found hidden above them were nearly full-height windows. Maximizing natural lighting also meant adding to the project’s beauty so that the added plus of energy efficiency feels inevitable, a happy coincidence that is the result of optimizing embedded design knowledge rather than an “engineered” solution.

Overall, the partnership between PLY+, the University of Michigan, and the Fitzgerald neighborhood is one that fits the profile of Detroit’s recent successes: After decades of decline, the city is already showing itself to be a model of community-led revitalization that works from the ground up. The Immaculata building has stood on its corner for over a century and has become a “neighborhood anchor,” to quote a local news channel’s coverage of the project. Neighbors are invested in not only preserving this architectural landmark but in ensuring its new use is by and for them—meaning, local residents—and not a ploy for outside investors or a tool of gentrification.

“It’s amazing to see this story of revitalization play out in a city and community with the history and energy of Detroit,” Maigret said. Despite well-intentioned hurdles, the design beautifully mixes old and new. While the more adventurous, formal design concepts first developed by Maigret and Borum were turned down by the landmarks commission, the success of the Marygrove project may begin to rebuild the trust between preservation and development. There is much interest among younger generations in cultural heritage, but not at the expense of experimental design ideas: Historic fabric can and should be seen as a fertile ground for conceptual play, especially as questions of carbon sequestration take center stage in debates over development. PLY+’s beautiful drawings—completed even for aspects of the project that went unrealized, like the gently lilting corridor intervention—are a lively example of architects showcasing their capacity for imagination, whether or not the construction drawings get signed.