Greta Gerwig’s Barbie introduces us to the latest version of Barbieland, a bright millennial-pink world where Barbie is everything. Gerwig’s decision to build a set from scratch follows a long history of world-building at Mattel, a pursuit embodied by the transformations of Barbie’s Dream House throughout time.

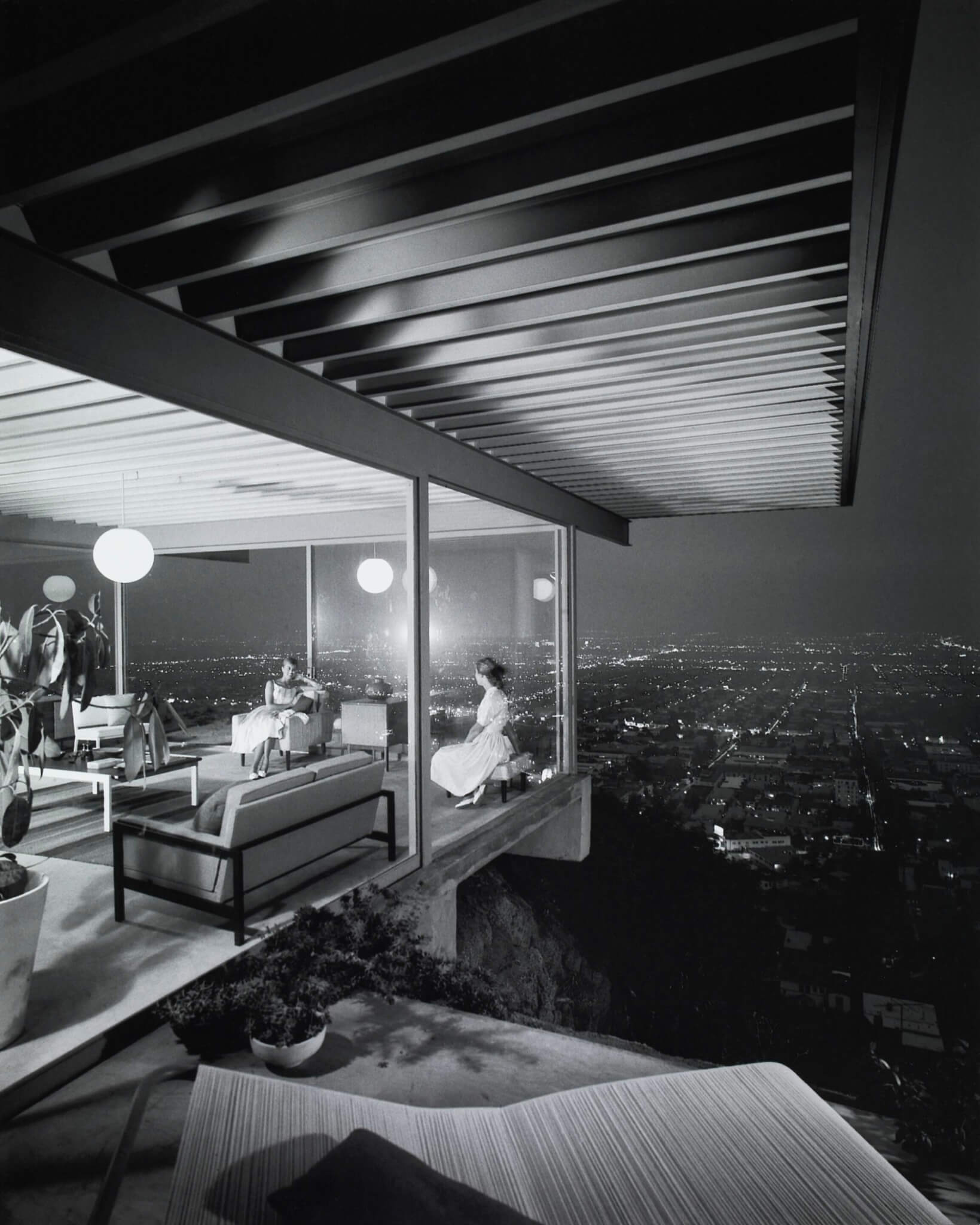

Barbie’s set design, by Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer, references midcentury design espoused by the likes of California architect Richard Neutra and as seen in the lush lifestyle photography of Julius Shulman and Slim Aarons: Together, these figures embody an aesthetic associated with what cultural critic Bill Osgerby described as the birth of a new kind of 1960s domesticity. Ironically, this cultural transformation was captured in two different, yet related, designed utopias: Mattel’s Barbie Dream House and the Playpad Series of Playboy magazine.

The first-ever Barbie Dream House hit stores in 1962. It was a foldout cardboard studio that contained a single bed, closet, dressing table, and a stereo/TV console—a hot new gadget. At a time when it was rare for women to own homes, the Barbie Dream House was a soft revolution. By folding, arranging, and rearranging, girls were able to build a world—albeit unoffensively in miniature—of their own.

That same year, Playboy published “The Playboy Town House: Posh Plans for Exciting Urban Living,” an article that featured drawings by R. Donald Jaye of a utopian bachelor pad. The glass and steel midcentury modern home was also a sort of dream house, with three floors of entertainment spaces and an indoor pool, all controlled with a central electronic system. Jaye’s article was the first of what became the Playpad Series, a recurrent column that went on to feature the architecture of Ant Farm, Charles Moore, Chrysalis, and Pierre Koenig, to name a few. The monthly column supported an all-male, Kendom-style world order: Power and independence were also asserted through midcentury modern environs, but felt exactly like the inverse of Barbie’s Dream House.

In the 1960s, both Mattel/Barbie and Playboy were effectively redefining domesticity. On one hand, the Barbie Dream House operated within the restrictive parameters of an infantilized female imaginary—a moralistic, asexual world ruled by fetishistic denial, as professor and film critic Pietro Bianchi points out. In contrast, the Playpad Series was inventing a new masculinity altogether. A “new man” emerged, according to Paul Preciado in Pornotopia, as an apolitical consumer created by the society of abundance.

Playboy’s new masculinity deviated from the traditional rugged and outdoorsy type that represented the white American man, moving instead towards an “indoors man:” a style-conscious, hedonistic consumer. This challenged the conventional paradigm that men are producers and women consumers, supported by other lifestyle magazines of the era. The Playpads reclaimed the architecture of the home as a space for male consumption by removing all feminine associations attached to commodity culture: the nuclear family, maintenance, stoves and dishwashers. Instead, technology prioritized entertainment-only gadgets.

Barbie’s cardboard Dream House included a stereo/TV console, but this detail ballooned into a full “entertainment wall” in the original Playpad of 1962, with a whole room dedicated to it. Also, the bed was reimagined as a built-in fixture/appliance, with a panel inset in the headboard that controlled the entire house—an early version of Hugh Hefner’s iconic rotating bed with phone lines and other office-like infrastructure. These enticing inventions were drawn next to real, ready-for-sale furniture pieces that were cataloged on every page, with pricing included: Clearly, a modern man need not separate work from pleasure.

More than half a century later, Sarah Greenwood, Katie Spencer, and director Greta Gerwig reference some of the most canonical architectural works of that era. Barbie’s Dream House, with its free-floating slabs, thin toy-like columns, and stone-clad chimney, is a formal homage to the Kaufmann House by Richard Neutra. Completed in 1946, this house was a predecessor to the Playpads in that it was an architecture conceived not as an object of devotion but as a container of spectacle, as Sylvia Lavin explains.

The Kaufmann House was made internationally famous through the photography of Julius Shulman which, according to Simon Niedentham, glamorized the house using the same narrative strategies as Playboy, depicting Neutra’s design as a piece of compelling architectural fiction selling a luxurious and sensual lifestyle. Shulman shared this sensibility with Playboy, who also published his work, including his legendary Case Study House #22 photograph of Pierre Koening’s Stahl House.

Barbie’s set design also references the work of Slim Aarons, a renowned society photographer who helped cement Playboy’s mythology through his 1961 photographs of Hugh Hefner’s parties. Aarons photographed the Kaufmann House in 1970, more than 20 years after Shulman’s imagery, and his photograph Poolside Gossip re-introduced it as a symbol of a luxury lifestyle, now for a liberated—or, at least, free to consume—society. In that sense, objects become important signifiers of status, which Barbie picks up throughout the set styling. Also, the central pool as an idealized social space to see and be seen, a theme present since the first Playpad publication, is on full display.

The shared references between both Barbie and the Playpads could be seen as a sort of feminist reconquest of the icons that were so heavily associated with masculinity. But, overall, they show that there is a common sensibility between both: a consumerist society where everyone is the spectator and the spectacle at the same time. By the end of the 1960s, Playboy had print runs of around 5.6 million copies, selling aspirational images of Playpads that few men could ever own in real life. Nevertheless, many did start to conceive themselves as the kind of man who would buy one—a seemingly free man who was trapped in a prescription of what liberation should look like. Now, Gerwig’s Barbie has surpassed $1 billion in ticket sales and her Dream House for the liberated woman seems to be shaped and constrained by some of the same logics of a consumer-driven spectatorship.

But, even within the formulas of commercial success, maybe there is a possibility for radicality in seeing ourselves buying into Barbie’s more open-ended mantra: “You can be anything”.

Daniela Beraún is a Peruvian architect based in New York City. Her interests include architecture narratives that relate to pop culture and politics.