While Querétaro may not be your top Mexican design destination, perhaps it should be. It’s home to some of central Mexico’s best-preserved colonial architecture, boasts a long history of craft, and, recently, has been undergoing a revitalization. In an area with such tangible history, it makes sense to embrace the concept of adaptive reuse to help connect the old with a welcome surge of new. In the capital city of Santiago de Querétaro, local architecture firm GOMA has done just that: Within the industrial bones of a historic textile factory that once employed 10 percent of the workers in the state, GOMA has retained the architectural character, as well as the history of labor embedded in the old factory, but updated it to serve a burgeoning new generation of creatives and artisans. The result has opened the city up to new visitors.

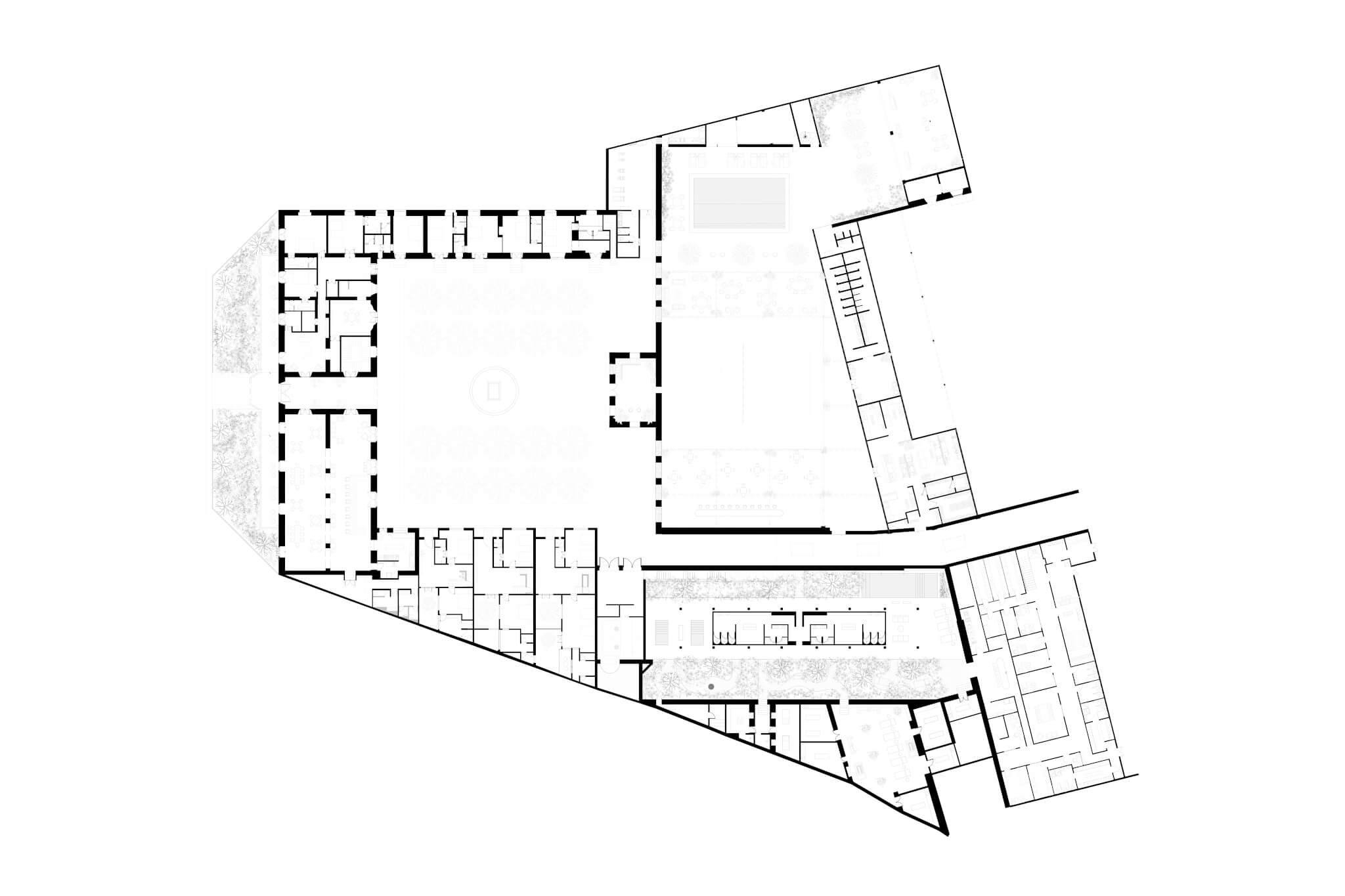

Hotel Hércules is a 40-room hospitality project complete with all you’d expect of a new destination: spa, pool, restaurant, and what the designers are calling a “social club.” Programmed into the bones of defunct warehouse, manufacturing, and employee-housing spaces, this revitalization opts for a lighter intervention that both minimizes construction emissions and pays homage to the site’s 175-year history.

Hot on the heels of Mexico’s industrial revolution, Fábrica el Hércules was founded in 1846 and, until it closed its doors in 2019, was Querétaro’s oldest operating factory. Struggling to compete with textile production overseas, though, the company had been downsizing its 470,000-square-foot operation for a number of years prior. In 2011, an unused wing of the factory was converted into a brewery—Cervecera Hércules—a welcome newcomer to the local scene. This early experiment in transforming the factory space became a place for tastings, informal gatherings, and events, rather than an example of abandonment or vacancy. The success of this first adaptation was quickly recognizable in the additions of an open-air beer garden, dance hall, shops, offices, and creative studios.

Much of this development was steered by current Hércules tenant GOMA. In addition to the execution of the beer garden, community offices, and warehouse storefront, the firm has most recently completed the complex’s largest adaptation yet: To transition Hércules from a locals-only spot to one that invites a wider audience, a new hotel has been inserted into the industrial fabric. GOMA renovated what was originally the factory owner’s on-site residence into a warm, pink courtyard hotel. The goal was to balance the expected refinement of a destination hotel within the more industrial history of local labor. Skillfully, GOMA holds both of these stories in the factory’s rugged shell.

Hotel Hércules retains the shape of the original house, designed with the age-old design strategy of the central courtyard. With all rooms of the home opening onto both the internal courtyard and the perimeter grounds, the house was cooled via cross-ventilation in an era before air-conditioning, and still today still allows for abundant sunshine and good views from all the rooms. The landscaped space is a quiet refuge for visitors, planted with olive trees and showcasing intricate detailing in the original stone ornamentation and Ionic columns. These 19th-century flourishes, along with a commanding marble statue of Hercules flanked by lions at the center of the courtyard, are some of the last that remain within the updated concrete complex.

Common areas such as the lobby, dining room, and lounge achieve a refined yet relaxed aesthetic through a careful infusion of greenery and an eclectic selection of vintage furniture sourced from markets throughout Mexico City. United in their deep wood tones, some of the furnishings lean traditional, while many incorporate the ever-popular midcentury modern feel into the mix. This carries through pine-framed doorways into the guest rooms, complete with low-slung headboards and deep armchairs carved from wood. Operable windows ensure abundant fresh courtyard breezes.

Traditional Mexican craft appears in the form of hand-painted tiles as well as thick textile wall hangings. Peppered throughout the private and communal spaces, these sculptural accents are produced by Caralarga, a tenant of the Hércules creative complex that manufactures jewelry, apparel, and home accents using recycled textiles and fibers.

But behind these modern accents and artful details, evidence of the factory’s industrial past is still revealed through the preserved, patchy concrete walls, exposed steel beams, and brick barrel vaults that constitute the structure of the space. Designers take this fragmented history one step further by also placing curated pieces of old equipment throughout the property. But like many arts complexes and residences before, Hércules also takes advantage of the loft-style proportions of the industrial spaces, offering guests generously sized rooms and impressive ceiling heights that nevertheless feel warm, welcoming, and filled with light.

“The greatest challenge was to create a serene oasis within an urban place without imposing too much of our design,” noted GOMA founding principal Carlos González. As is evidenced by the thoughtful restraint throughout the hotel, the firm’s “less is more” approach extends outward to the new, exterior amenity spaces. Here, porosity and greenery play a large role in shifting the factory ambience.

Following a similar treatment in the Hércules beer garden, the architects carefully peeled away portions of roof in the factory’s former fiber separation, or “carding,” room to create the Buenavista social club. By subtracting six teeth from the expansive, sawtooth structure, the designers were able to transform the space into an open-air venue complete with a grass volleyball court, pool, and covered terraces. Able to accommodate up to 700 people, the flexible space has hosted concerts and other large gatherings, including a communal meal for former textile factory workers and their families, who were invited to explore the renovation ahead of the hotel’s opening in June. Bold remnants of the roof structure remain above the green spaces as a reminder of the space’s past life.

Interventions are similarly light in the outdoor spa, with only the injection of one freestanding bathroom structure between an existing bay of bright, blue-dipped columns. Throughout the surrounding courtyard, sunken hydromassage and hydrotherapy pools cut through the expansive concrete floor plate, which has been enhanced by lush, local plantings. Inside existing manufacturing spaces, GOMA introduces massage cabins and saunas; a “relaxation room” punctuated with more of that preserved, defunct textile machinery; and a vapor chamber clad entirely in tiles glazed a calming blue hue.

Upon reflection on this adaptive reuse process, González noted, “If all you’re focused on is the numbers—profit, units, square footage—everything becomes an obstruction instead of an opportunity.” Rather than razing and erasing the site’s industrial past to achieve its newfound refinement, the design for Hotel Hércules capitalizes on the aesthetic and ultimately sustainable advantages of working within the substantive history and infrastructure of the existing site. This strategy not only permits a unique design that is deeply rooted in place but also illustrates that “new” doesn’t always equate to “good” and that there is inimitable opportunity within the existing built environment.

Sophie Aliece Hollis is an architecture and design writer in New York City.