Print Ready Drawings

Curated by Sarah Hearne

MAK

Los Angeles

November 11, 2023–February 4, 2024

Architecture exists between and among formats. Where/what is architecture, exactly? Can it be located within the buildings themselves? Or in the drawings, models, images, specifications, and publications made by architects? Such instability means that architectural knowledge is made transmissible through architectural labor: Information is constantly being drafted, copied, reproduced, translated, enlarged, reduced, cropped, edited, finalized, uploaded, published, communicated, and shared. As curator Sarah Hearne wagered in Print Ready Drawings: Composites, Layers, and Paste-Ups, 1950–89 at the MAK’s Schindler House in Los Angeles, the ink matters more than the paper. The show smartly collected a range of artifacts that together argue for the layered requirements of media production. They make visible the labor of reproduction, tasks that evade awareness when only evaluating the singular, compressed surface of an image.

Hearne’s show emerges from her recent PhD dissertation at UCLA in which she examined “the architect’s work in relationship to the move from industrial to post-industrial labor paradigms in the mid-twentieth century, with architecture’s output shifting increasingly toward activities such as publishing, research, exhibitions, and object design.” Rather than authorial design drawings, she “explored the documents that were clearly duplicative and perhaps bureaucratic, that were marked by reproduction and publishing.” Some artifacts of interest—and the ideas they stir up—are worth considering even after the show’s closing in February.

Print Ready Drawings zooms in on processes of material reproduction in the post-war, pre-digital era. Hearne’s staging makes visible the preparatory drawings, layouts, sketches, and correspondence that exist between a design and its mediatized absorption by its audience, showing know how much of the conceptual iceberg lies beneath our optic ocean—hidden, still powerful, awaiting our attention.

As Hearne writes in the newsprint publication that accompanied the show, “circulating through this exhibition is a stream of advertising, articles, manuals, and ephemera that illustrate the various ways that manufacturers of supplies invested in the imagery of systematization, innovation, and efficiency. Yet, these items were not widely understood as technological objects.” She asks: “Was this lack of consideration a cover that enabled materials and supplies to pass our attention as possibly important yet invisible actors in the structuring of architectural authors?”

Across the intimate rooms of the Schindler House, a series of custom vitrines with foldable arms are finished in a range of stains and sit on sawhorse-like legs. Handsomely designed and fabricated by Current Interests, they read like camp kitchens or the portable cabinets set up on an archeological site.

An introductory film from 1971 by Gianni Pettena focuses on what happens before a designer begins to draw: Pettena’s subject stalls, attending to his hair, nails, and ears, prior to beginning work. “The film asks us to consider drawings as made for the camera-eye,” Hearne wrote. What is on display is the entanglement of “copyists and technicians” with “authors and conceptual designers.” The video mixes the ideas of avant garde operators—one of whom made a film seemingly about nothing—with the realities of “technocratic and technical necessities of corporate architecture in this period”—meaning, the need for draftspeople to draw with a certain efficiency. Throughout, exhibition copies and supporting films by Julie Riley and Jenny Levitt offer a contemporary viewpoint on reproduction and recreation efforts.

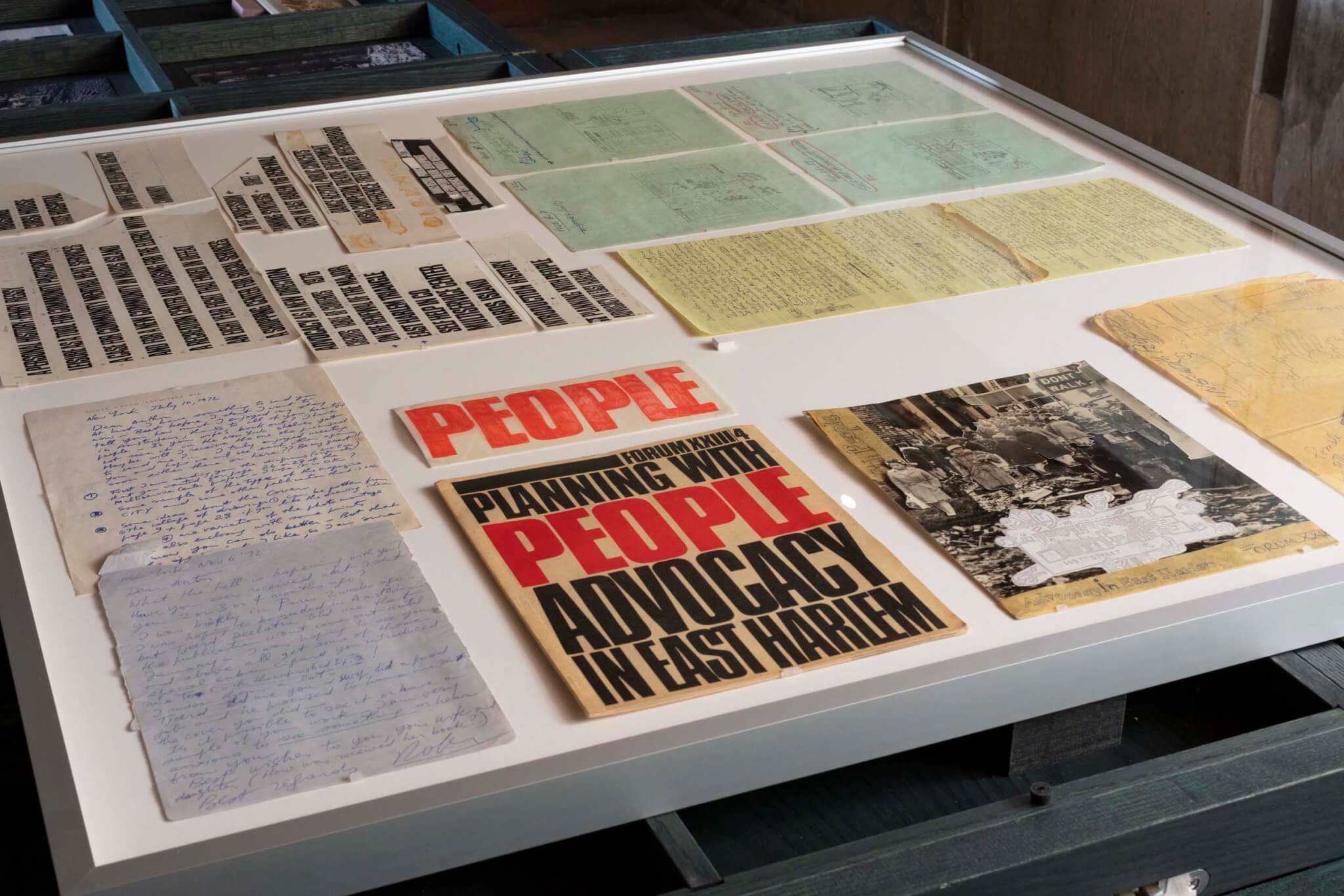

In one room, a series of unrealized covers for Habitat designed by Lina Bo Bardi are set against impassioned correspondence about a cover for Forum and a range of archival materials from the Young Lords. The traffic about magazine production reveals the plethora of actors who participate in its realization, namely “an engagement with editors, typesetters and layout technicians, printing presses, advertising, and stock-photography companies.” Though perhaps the roles have shifted or collapsed, the arrangement remains true today.

Another area, titled Worlds on Paper, hosts documents that “were all designed to change status under the camera-eye or through some form of processing to become an image, whether printed or projected as film.” Perhaps the most striking case study—and one sourced from Hearne’s thesis—is a photo of what appears to be a model of Peter Eisenman’s House II, but which is actually a treated aerial photograph. Hearne wrote that “following [Eisenman’s] removal from the project, the client entrusted the completion of the house to Tadas Zilnius, a designer who had moved to New Jersey to work for the timber toy company Creative Playthings. …Sometime after the completion of the house, this aerial photograph was captured by one of Eisenman’s assistants, Randall Korman, who had flight training from his time in the military and authorization for light plane rental. Korman was sent to take a photograph of the house as a ‘proof’ that the house looked like a model, so long as it was viewed from an aerial vantage. A photo selected from the contact sheet was sent to the lab for retouching, and a combination of editing processes “was applied to the photograph in order to isolate the house from its scale, context, materiality, and inhabitants.” The result is a mute, model-like image that communicates not its actuality but instead its similarity to the “smoothness of cardboard,” an interest that grew throughout the American architectural academy to read buildings as abstracted items and not as laborious constructions made of real things.

A section from Le Corbusier’s stadium proposal for Baghdad is also notable. Sourced from the collection of Drawing Matter in the U.K., the drawing shows alterations with “cut-outs, overlays of crayon, and white paint to conceal areas of alteration,” evidence of the process of editing a drawing prior to the easy erasure of CAD linework. It was produced by Guillaume Jullian de la Fuente, one of the only assistants who remained on the Baghdad project after a pay and credit dispute caused everyone else to leave. Apparently, Le Corbusier changed the locks of one of his ateliers as a means of “expunging” the staff from his workplace.

The last room deals with the arrival of computation. Cedric Price’s La Villette competition entry appears, as does a print of OMA’s Exodus project. The documents showcase a moment when offset printing replaced letterpress and the arrival of Letraset, which “transformed the printing press into more personalized forms of production.” Hearne states that “these activities reflect the intense print- and graphic-orientated culture that arose related to the proliferating consumer market around image-making supplies.” Another piece of ephemera is sourced from the printmaking efforts of John Nichols in New York’s Soho neighborhood, whose archive is now a central resource for a83, a printshop and gallery—and AN stockist—run by Owen Nichols and Clara Symes.

Finally, the show’s supplemental newsprint takeaway cogently articulates the curatorial ambitions for each setting. The printed item means a viewer can think through her claims even at a distance after the show’s closure. (What became of those nifty camp kitchen displays?!) The item is yet another form of translation: It zooms out from the histories embedded in the pieces on view to deliver textual scholarship that locates these items in a continuum, a welcome scholastic conversion. Its ink stained the fingers used to type this review.