“I’ve done a lot more in my life than just this!” Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, then in her late 90s, told a reporter in 1997. The Austrian architect had been asked about a project she was sick and tired of being asked about. “If I had known that everyone was always talking about it, I would have never made this damn kitchen!”

Indeed, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky was much more than the widely celebrated Frankfurt Kitchen she designed in 1927—a project which catapulted her into the annals of modernism. She was also an antifascist resistance fighter that risked her life battling Nazis during World War II, an anti-Vietnam War activist, a militant feminist, and a bonafide communist that dedicated her life to the working class. And, yes, she was also a damn good architect that designed kitchens, social housing, nurseries, kindergartens, and so much more.

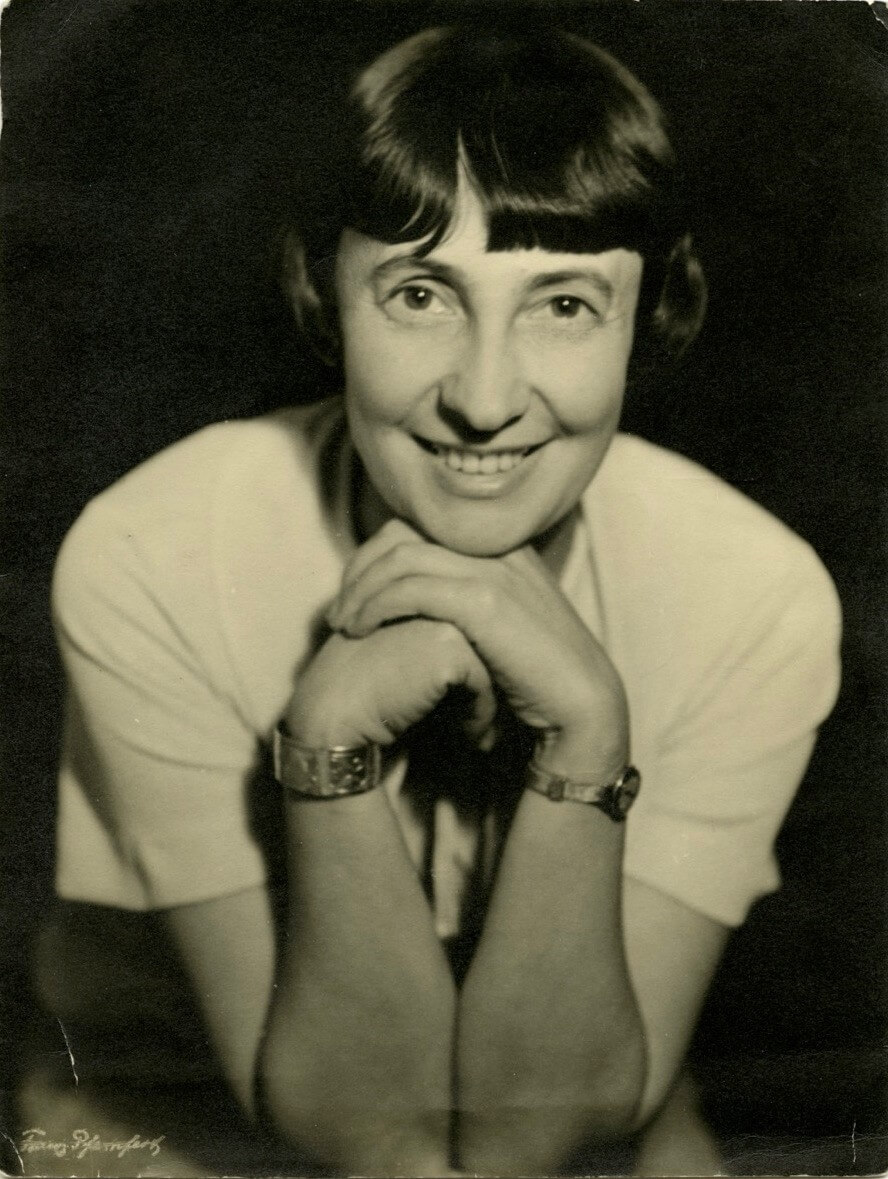

At the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, a new exhibition, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky: Pioneering Architect. Visionary Activist, captures the full spectrum of the late architect’s contributions to design, and society at-large. The show was co-curated by Dr. Stephanie Buhmann and Dr. Bernadette Reinhold in collaboration with the Collection and Archive at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. The retrospective, which opened March 11, showcases original drawings, architectural plans, and models by Schütte-Lihotzky, along with personal photographs and correspondences that tell her remarkable life story.

The exhibition spans multiple floors of the Forum’s building that Raymund Abraham completed in 2002. Visitors are immediately transported into the exhibition in the building’s lobby, where a timeline gives big picture information about the architect. There, they are also met with a music video featuring Rob Rotifer’s 2008 pop-punk tribute to the architect, entitled The Frankfurt Kitchen. (Rotifer’s own grandmother had fought in the underground resistance with Schütte-Lihotzky, which inspired him to write the song.) After ascending from the lobby, guests can enjoy scale models of the Frankfurt Kitchen, accompanied with detailed descriptions and even a black-and-white silent motion picture from the late 1920s about the canonical project.

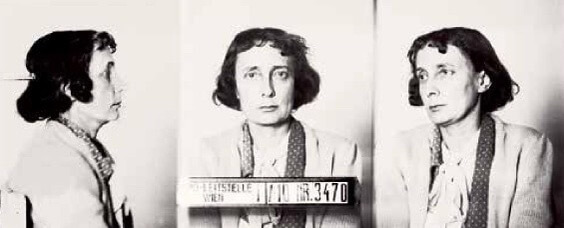

While the floor dedicated to the Frankfurt Kitchen delivers what one may expect in a show about Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, the subterranean level casts the late architect in a new light. There, a central table displays Schütte-Lihotzky’s personal ephemera including her prison notebooks, kept after getting arrested by the Gestapo. Viewers who may have read about her in architecture school, or stumbled across her in the footnote of a monograph, quickly find out there’s much more to Schütte-Lihotzky than meets the eye. Or, to quote Elisabeth Holzinger, “Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky may be well-known as an architect in the meantime, but too little is known about her as a political person.”

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky was born on January 23, 1897, in Vienna. She came from a middle-class family living in Vienna’s fifth district. In 1915, Margarete enrolled at the School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna, known today as the University of Applied Arts. There, her professor, Oskar Strnad, challenged Margarete to study living conditions for workers. For her research, she won the Max Mauthner Prize in 1917. In her curation, Dr. Buhmann emphasized that it was Oskar Strnad who infused in Margarete a deep sense of social responsibility, one that she would carry her entire life.

One year after founding her studio at age 24, a new social democratic government in Vienna was elected to power in 1919, the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Austria. This ushered in the period known as “Red Vienna,” the subject of Eve Blau’s book which captures the epoch’s scintillating zeitgeist. The new leftist government made social housing, education, transportation, and infrastructure for the masses its utmost priority; a good time to be an architect!

Schütte-Lihotzky’s first major commission came in 1921 when she was tasked with designing the First Non-Profit Settlement Cooperative for Austrian War veterans, a project she worked on with Ernst May and Adolf Loos. Her next big break was in 1926 when May hired her to design kitchens for workers in Frankfurt. In total, 10,000 of Lihotzky’s kitchen designs (known today as the Frankfurt Kitchen) were installed in flats throughout Frankfurt.

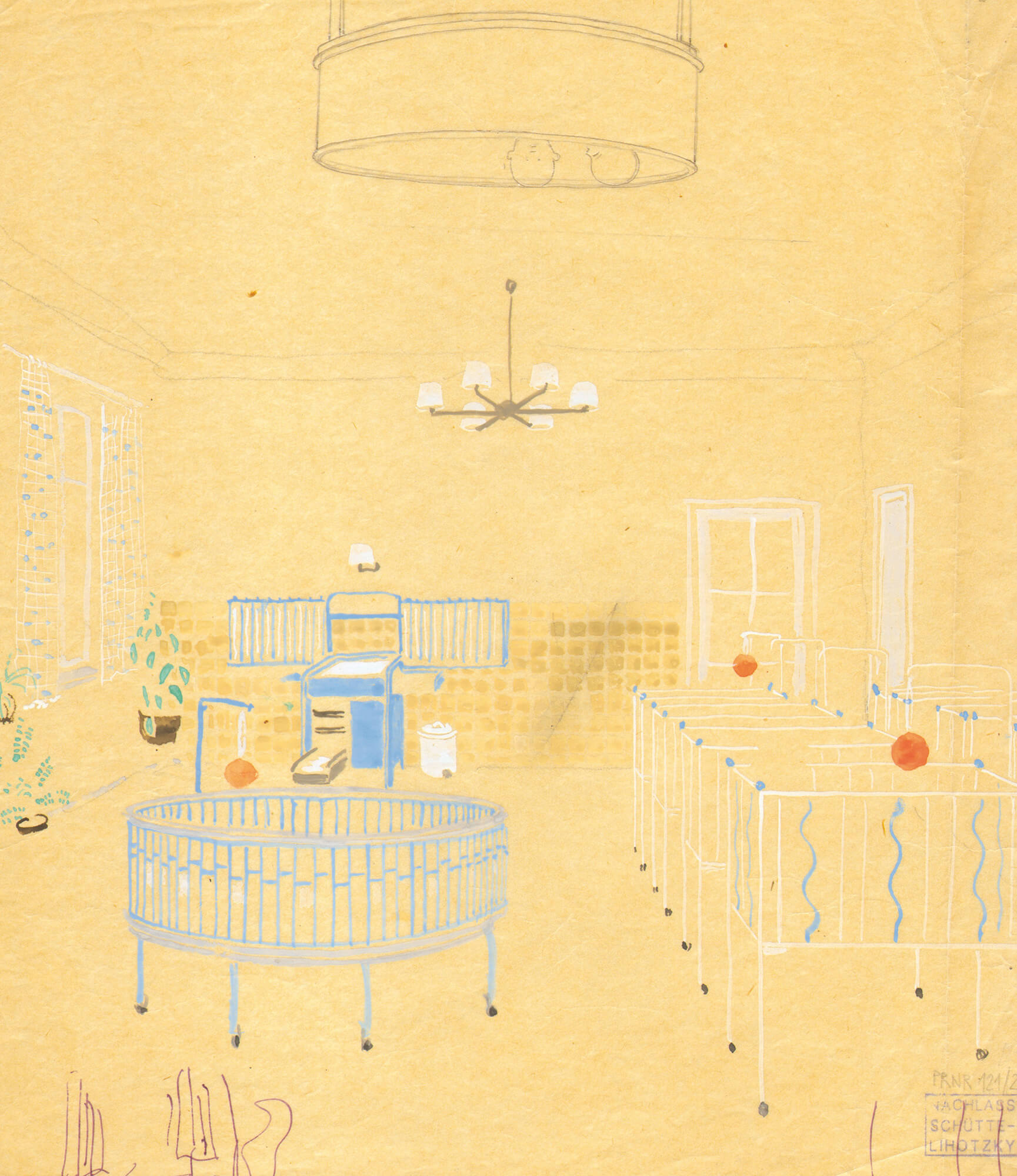

Meanwhile, the threat of fascism increasingly loomed over Europe, and Schütte-Lihotzky became even more politically active. In 1930, she enlisted in the “May Brigade,” a group of 17 communist architects led by Ernst May who decamped to the Soviet Union, where she began designing kindergartens and master plans. In the USSR, she infused her understanding of Montessori principles into the design of schools, and even baby furniture. There, she also collaborated with Ivan Leonidov on a master plan for Magnitogorsk, and another one for Briansk.

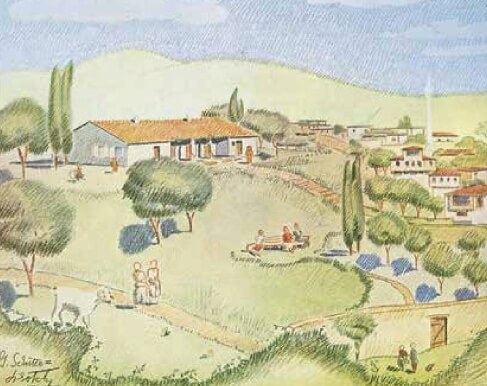

Things changed in the Soviet Union in the late 1930s when Stalin’s cabinet began arresting foreign experts. Schütte-Lihotzky managed to escape the persecution, but many of her former collaborators weren’t so lucky. In 1938, she relocated to Istanbul, and took on commissions from the Turkish Ministry of Education: She designed a secondary school for girls in Ankara, and a village school in Anatolia. The projects were part of President Kemal Atatürk’s campaign to increase literacy rates around the country.

It was also in Istanbul where she made contact with Herbert Eichholzer, a fellow architect who had previously worked for Le Corbusier only to leave architecture and join the fight against fascism. Between 1938 and 1941, Schütte-Lihotzky was a spy in an antifascist syndicate led by Eichholzer, along with her husband Wilhelm Schütte.

Certainly, this was a colorful life for any architect, one that was definitively different from most other modernists in those interwar years. While Schütte-Lihotzky and Eichholzer were fighting fascists, Bauhaus figureheads like Walter Gropius were enjoying cushy desk jobs at Harvard, and Mies van der Rohe was even cozying up with the Nazis in search of commissions. On January 22, 1941, Schütte-Lihotzky was arrested by the Nazis. She was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in Aichach, Bavaria, because she refused to cooperate; and Eichholzer was later executed. All this while Gropius was enjoying tea time in Cambridge and Mies was reinventing himself in Chicago.

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky was liberated by U.S. soldiers on April 29, 1945. Upon returning home to Austria, she quickly joined the massive movement to rebuild Vienna. She tried forming a new Central Building Institute for Children’s Institutions to meet the urgent demand for nursery schools, kindergartens, children’s playgrounds, children’s clubs, and overnight facilities for the children of working mothers. On November 1, 1948, a monument she designed indebted to the victims of fascism with Fritz Cremer debuted in her hometown.

But despite her valiant efforts against Nazism, Schütte-Lihotzky’s career after World War II was bleak. Manfred Mugrauer, among other historians, contended the scant amount of work she was given is due to one main reason: Her status in the Austrian Communist Party. “Her being a communist, an anti-fascist resistance fighter, and also a woman doomed her to social oblivion in the postwar era when the focus was on restoring the old order of an earlier age,” wrote Marcel Bois and Dr. Bernadette Reinhold in an anthology they edited for Birkhäuser about the architect.

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky had just a handful of major public commissions after the war, including Kindergarten on Kapaun Platz (1952) and Kindergarten Rinnböckstraße (1963). But even after the far-right crept its ugly head back into Austrian politics in the 1980s, she remained a thorn in their side: For example, she sued the right-wing Freedom Party of Austria in the 1990s for statements its chairman, Jörg Haider, made that trivialized the Holocaust.

Before she died in 2000, Schütte-Lihotzky donated her archives to the University of Applied Arts Vienna. There, her treasure trove of drawings and notes sat for decades until Dr. Stephanie Buhmann and Dr. Bernadette Reinhold proposed a retrospective dedicated to the late architect, now on view at the Austrian Cultural Forum of New York.

Upon leaving the exhibition, one walks away inspired by a great woman, but also dumbfounded, and even irritated. How (and why!) could the modernist canon reduce this revolutionary designer who risked her life fighting fascism into someone who merely worked on a kitchen? Why are the Mieses of the world held up on pedestals when, at their best, they sat out the fight against fascism and, at their worst, sucked up to the Nazis?

The answers are obvious: Patriarchy, misogyny, essentialism, and anti-communist fervor, to name just a few pernicious forces. It’s a travesty that it’s taken so long for these drawings, photographs, and prison notebooks to see the light of day. But at least now they’re out there for the world to see. Hopefully the exhibition inspires this generation to follow her lead.