Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence

V&A Museum

London

Through September 22

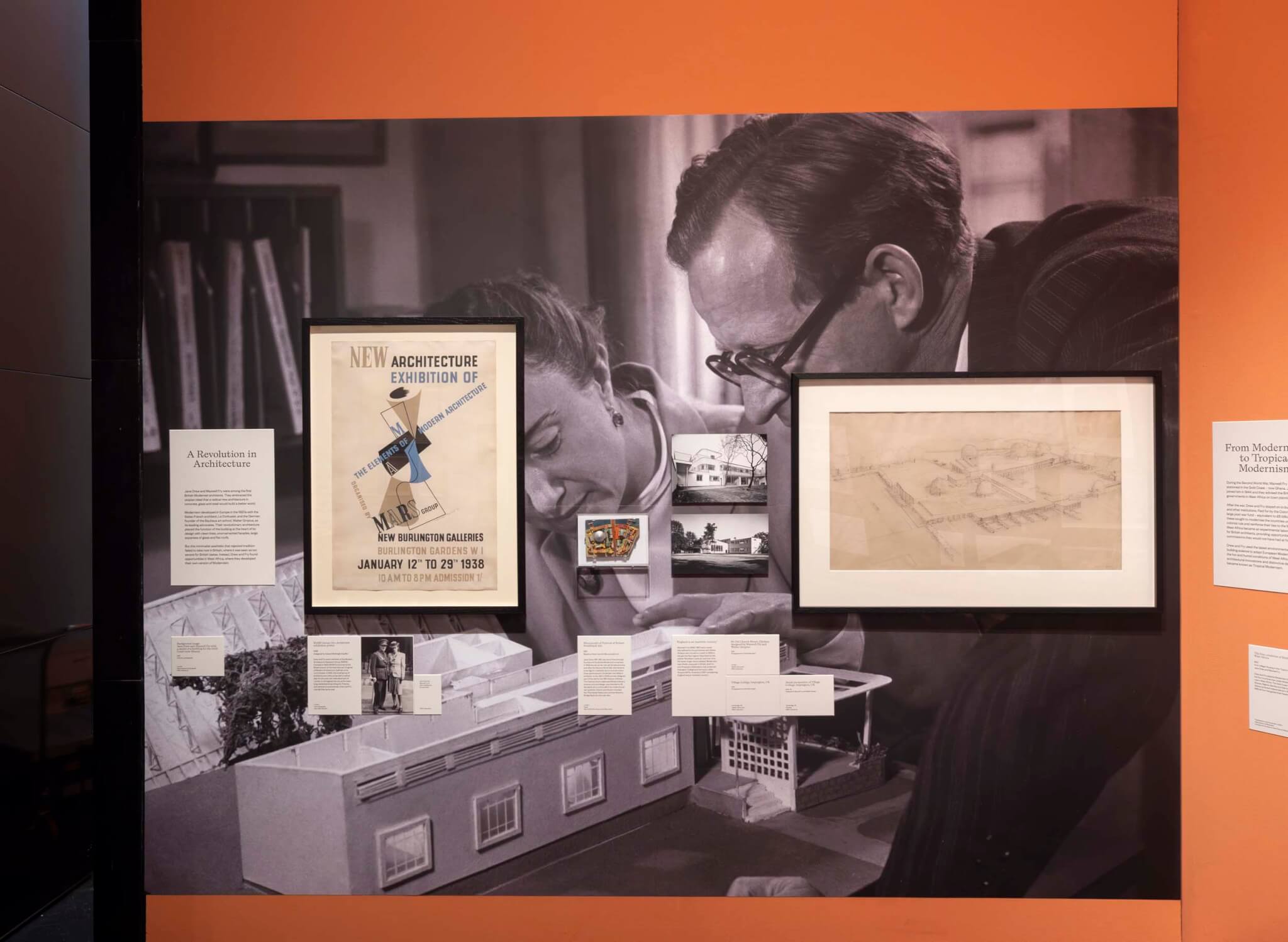

Staged in the V&A’s Porter Gallery, Tropical Modernism is a densely packed exhibition, trotting through 20th-century architectural histories in Ghana and India. Divided into rooms based on both geography and chronology, the exhibition invites viewers to explore the development of architecture in these postcolonial contexts.

The exhibition begins with an introduction to Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew and their arrival in the tropics in the 1940s. The room feels dimly lit in contrast to the entrance vestibule, and focused light beams down on glass vitrines featuring reading material, wall mounted maps, and archival photography narrate their initial years in the region.

Attendees read of Fry and Drew’s postwar building efforts following Fry’s appointment as Town Planning Adviser for West Africa, and the subsequent recruitment of Jane Drew and others to work at pace to deliver new schools and institutional buildings. The movement began with small-scale tests of materials, motifs, and coloration, not necessarily seeking to find a new form of architecture but to test the limits of modernism—and find a new regionally specific application.

The installation design subtly communicates some of these initial tests, with a large dividing screen in the first space modulated by the undulating rhythm of a Brise-soleil and a large cut-out window, similar to those used in Fry’s designs to facilitate cross-ventilation.

Sketches, and a 1:1 maquette of a facade panel also help to communicate the early search for a new form of architecture that responded to the climate, while also embracing a language of local forms. On another panel viewers see two of the “hidden figures” Fry and Drew depended on to shape a locally relevant architecture—Ghanaian architects Theodore Shealtiel Clerk and Peter Turkson.

The approach to the hidden figures behind the movement and activity at the Architectural Association’s Department for Tropical Architecture, which was initially supervised by Fry, Drew and James Cubitt, is quite limited. More insight into the figures who have long been seen as peripheral would have added greater depth to the exploration of Tropical Modernism in the museum context.

A single gray, concrete-like perforated screen seamlessly links together all three of the key rooms within the exhibition, helping to smooth out the transitions in time from Ghana to India and back again. In one moment, viewers are peering into a photograph of Fry’s Ghanaian studio space, and a moment later an enlarged black-and-white photograph portrays the meeting of Jawaharlal Nehru and Kwame Nkumrah in India.

The exchange of ideas between Nkumrah and Nehru is a pivotal hinge in the exhibition. Both sought to co-opt elements of the new, modern western style as a means of rejecting historic colonial oppression. The second room is dedicated to the exploits of architects and designers in India. There is a sense of febrile energy in the room: Walls are awash with bright orange paint and a central plinth features mounted models and replica furniture from the period. A significant amount of wall space is given over to exploring the formation of Chandigarh and the work of cross-cultural collaboration between the Europeans and local architects like Aditya Prakash.

Archival photography also highlights model makers Rattan Singh and Dhani Ram on display, who worked to translate Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier’s drawings for The Capitol Complex. Nehru’s wish to be free from the strictures of the colonial past was granted, but some later questioned whether there was enough of a tie to the national character in the new contemporary style. Large-scale drawings by Aditya Prakash explore what the planning framework could have been like if it had taken into account the reality of Indian culture, for example with space to trade goods and tend animals close to the home.

Another fast segue occurs via a large model of New Delhi’s Hall of Nations. Viewers are propelled into a lurid green space—Kwame Nkumrah’s political climax at the International Trade Fair of 1967. Bracketing the photographic and contemporary media commentary on the trade fair, plans and photographs highlight the rigorous dissemination of skills at Kwame Nkumrah University of Science and Tecnnology (KNUST).

Nkumrah saw knowledge as the path to boosting Africa’s status on the global stage. Wall-mounted photography narrates the invitation and arrival of prominent architects like Buckminster Fuller to support activity at KNUST. A large geodesic dome model made by KNUST students hangs over the space, and magazine clippings from the time, give a tangible sense of the celebratory feeling that would have filled the air

The academic engagement with design in the tropics is an elemental thread closely linked to the political purpose behind the movement. Having reviewed Jawaharlal Nehru’s efforts to establish a “living school” for local architects (led by Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew), and read of Nkumrah’s ambitions to usher in a new “Africanization” of the professions, viewers progress to the final, dimly lit space in which a short film is screened. John Owusu Addo, an architect involved in the early development of the Tropical Modernism movement, speaks fondly of his experiences at the AA’s Department for Tropical Architecture and the challenges of applying that knowledge in reality.

The film and the fourth space of the exhibition are somewhat somber, with a dismembered statue of Kwame Nkumrah surveying attendees as they witness the floundering of the movement following Nkumrah’s death. The film captures the decline following Nkumrah’s political triumph. We watch as he declares: “At long last, the battle has ended! And thus, Ghana, your beloved country is free forever!” and see the faded grandeur of structures like the Senior Staff Club House by Addo, Miro Marasović, and Nikso Ciko. Attendees leave the exhibition with new insights into the somewhat overlooked movement, but also with questions around how “the vision” behind any movement can be sustained in the midst of turmoil—and after the visionary has gone.

Josh Fenton is an architectural writer and communications consultant based in London.