Studio Gang is on track to complete the University of Chicago’s John W. Boyer Center in Paris by October. The school’s new international outpost sits in the 13th Arrondissement along the Avenue de France, a cavernous main artery whose mixed-use towers make it feel less like southwest Paris and more like New York’s Hudson Yards.

This ex novo district, called Paris Rive Gauche, isn’t Haussmann’s conception of broad boulevards and a unified vocabulary. It’s also not the postwar economic dream of La Défense on axis to the city’s historic core. It’s something Paris hasn’t seen yet: Platformed upon a massive train yard on a strict grid, the site offers firms like Studio Gang, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, and Dominique Perrault Architecture the chance to ignore Paris altogether.

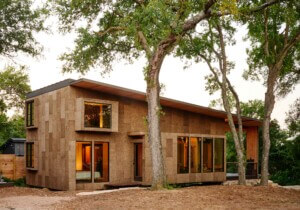

The Boyer Center consists of 5 stories of cross-laminated timber and glulam columns, beams, and panels above a steel and concrete podium that encases a busy stop for the suburban regional train line. Its program is not unusual—it combines both dedicated and flexible classrooms, lecture halls, informal meeting rooms, study spaces, and offices (not to mention a photo-friendly top level for public events, lectures, and champagne toasts). Its appearance is not conventional, either, compared with some of the wilder forms taking shape here, including Rudy Ricciotti’s ribbonlike Émerod flats, Hamonic+Masson and Comte & Vollenweider’s skewed Home, and BP Architects’s aluminum-paneled M9-C. What will make this project unique, however, is Studio Gang’s effort to make a single urban building feel like a capacious campus on perhaps one of the narrowest sites in the entire Paris Rive Gauche scheme.

“Part of the idea was to re-create the elements you’d benefit from in a more horizontal, residential campus environment,” said Rodia Valladares, the Boyer Center’s design lead and a design principal at Studio Gang’s Paris office. “That includes places for encounters and circulation and places of light and sightlines.”

Over the next couple of months, the building’s CLT panels will be clad with a composite stone, sourced 40 kilometers (about 25 miles) away from the same quarries as Haussmann’s 19th-century buildings—a strategy, Valladares said, that also connects it to the university’s stone buildings in Chicago 4,100 miles away. He calls it both a veil and a thin Brise-soleil for a “campus” constructed within a single building.

Valladares recently took me through the unfinished building. As we dodged stacks of materials and half-poured floors, each new level on a gray day was brightly lit by generous windows that framed the broader story about the 13th Arrondissement’s transformation beyond. We circumscribed the central atrium that connects this campus, named for the distinguished and longtime Chicago dean and historian John W. Boyer. It was funded by $27 million in donations from UChicago alumni and parents, including $10 million from the Shelby Cullom Davis Charitable Fund. At 25,460 square feet, it will reportedly be triple the size of the university’s current Paris center, a few blocks away, which opened in 2003. In this way, UChicago was early to the game, whose rules were set by SEMAPA, the development corporation jointly administered by the French national railway (whose tracks it occupies) and the Paris city council.

Despite the additional square feet, it is indeed a tight site, measuring roughly 200 feet deep and 100 feet wide. The word “constraints” came up in our interview often, referring to the train station below, which had to support ongoing service throughout construction, the demanding acoustical requirements of an academic building, and the exigencies of urban campus security while fostering a sense of openness.

One thing that remarkably didn’t come up in conversation related to constraints? Paris itself. Not in this part of town. “Everyone along this street is trying to deal with the city of Paris, but with a much different geometry—a freer geometry,” said Valladares. “We thought about the 13th Arrondissement, and we thought about the city of Paris at large, but we began with the question of how we take this opportunity to create new ground, literally, that didn’t exist before the train platform.”

William Richards is a writer based in Washington, D.C., and Paris and the cofounder of Team Three, an editorial and creative consultancy.