It’s been almost a decade since June 17, 2015. That afternoon, a neo-Nazi entered Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church’s Fellowship Hall in Charleston, South Carolina, and murdered nine African American parishioners participating in bible study. The victims were Reverend Clementa Pinckney (41), Reverend Daniel Simmons (74), Reverend DePayne Middleton-Doctor (49), Reverend Sharonda Singleton (45), Cynthia Hurd (54), Tywanza Sanders (26), Ethel Lance (70), Susan Jackson (87), and Myra Thompson (59).

The 2015 attack rocked the nation, and even provoked South Carolina politicians to finally remove the confederate flag from outside the state capitol. This past summer, construction started on a memorial indebted to the nine victims, entitled the Emanuel Nine Memorial. The design is by Michael Arad, a principal at Handel Architects. Renderings of the project were released in 2017 but the project took longer than expected to break ground and is anticipated to partially open in spring 2025.

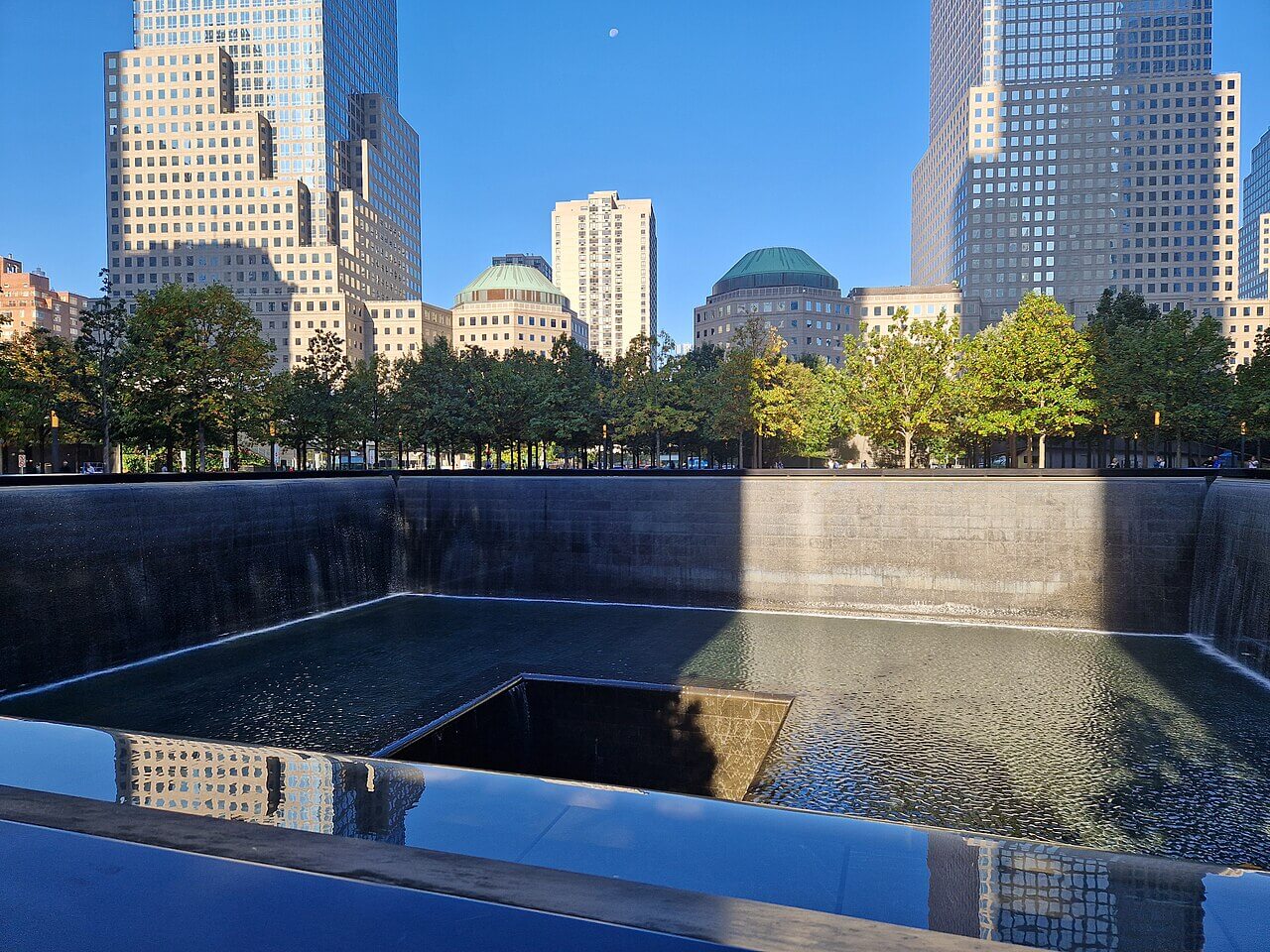

Michael Arad is certainly no stranger to emotionally charged projects. In 2004, he won an international competition to design the National September 11 Memorial in Lower Manhattan at age 34. But for many reasons, the Emanuel Nine Memorial was different. “I’m not Christian, I’m not African American. I did not personally know anyone who was lost. And I’m not from South Carolina,” Arad told AN. Thus, the question became: How does one go about designing such a sacred space for a community that you’re outside of?

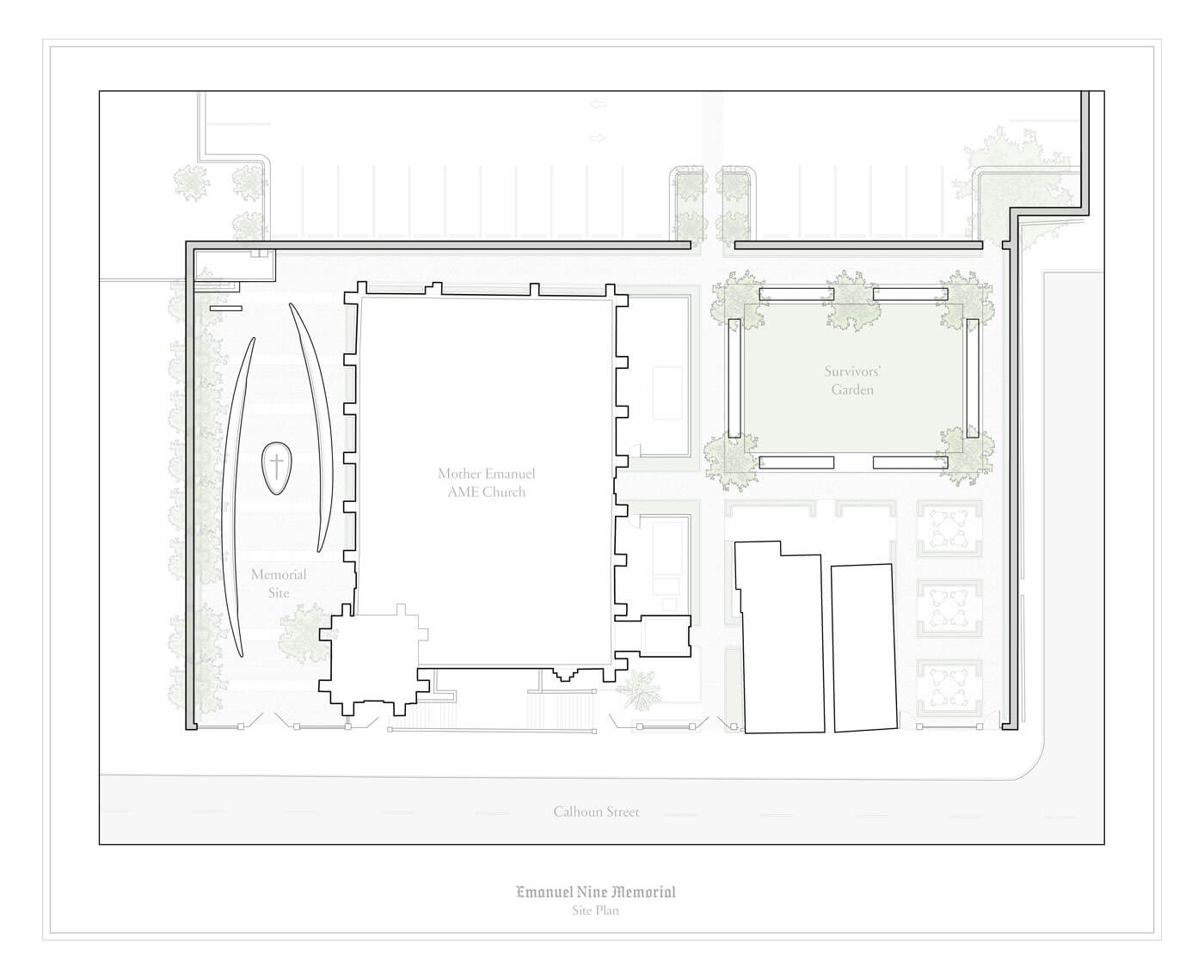

The Emanuel Nine Memorial has two distinct parts: a Memorial Courtyard and a Survivors’ Garden. The former is meant to honor those who were lost—it features custom designed fellowship benches that face one another made of marble. A separate marble sculpture is situated between the benches, which lead to a smaller, more intimate nook for genuflection and individual prayer.

The Memorial Courtyard’s central sculpture is etched with a crucifix and the names of the nine victims. A pathway then leads visitors to the Survivors’ Garden, which offers space for community gatherings. There, a green open space is located surrounded by six stone benches and five trees. Surfaces are covered by fig-ivy, brick, and stone.

The Emanuel Nine Memorial offers space that both honors those who passed, and those who lived—a design decision deeply influenced by the architect’s experience on the 9/11 Memorial.

“I learned so much from working on the 9/11 Memorial,” Arad recalled. “One of the many lessons was that the original design in Lower Manhattan didn’t acknowledge all of the people that died from 9/11-related illnesses in the years that followed. This wasn’t of course an intentional omission. But it was an omission. I remember meeting this woman, Sonia Agron, who was a first responder that worked at Ground Zero during the months after the attack. She once told me that when she came to the 9/11 Memorial, she didn’t feel like it was a place for her. To imagine her coming to the site and feeling as though there was no space for her was heartbreaking.”

To rectify this, a memorial grove was later added to the World Trade Center to honor the people who perished after the attack from their injuries, and for first responders more broadly. The hard lessons learned from that process paid dividends later in Arad’s life, as he was brought onto the Emanuel Nine Memorial design team. “I still remember coming to my office one Monday morning, and seeing an email from Janet Kagan,” Arad said, referring to the woman who started a working group for the memorial. “That time around, instead of the architect saying: ‘Here’s this design, we have it all figured out,’ we started our process of engagement based on a series of trials and errors.”

After the 2015 shooting, parishioners came together to grieve, and eventually heal. To that end, community leaders began ideating a memorial indebted to the victims. From there, employees from the Beach Company, a fifth generation South Carolina development group, reached out to offer their services, including Karen Brewerton and CEO John Darby. Dr. Maxine Smith, a longtime Mother Emanuel parishioner, began coordinating the seedling memorial effort on behalf of the church with Beach Company. A 501c3 subsequently formed led by Smith, Brewerton, Darby, and local community leaders to bring the memorial to life.

Dr. Tim Brown, a dean at Trident Technical Community College (who sings in the Mother Emanuel choir) was invited to serve as an advisor to the working group. Other advisors included Senior Reverend Eric Manning; Dr. Karen Chandler, an art history professor at the College of Charleston; Mark Sloan, curator at the Halsey Museum of Contemporary Art; and Marcus Amaker, a local poet. Janet Kagan was invited to organize a memorial competition and assemble a shortlist of architects for the selection committee. Afterwards, the working group promptly began reaching out to architects with a simple question: What does forgiveness mean to you?

“It certainly wasn’t like the other RFPs we get,” Arad told AN. “It was unusual for an architectural commission in the sense that they didn’t really ask for a design proposal. Instead, they asked me to write an essay about my understanding of the events that occurred in Charleston. And then they asked for me to reflect on the meaning of forgiveness. In hindsight, it seemed unusual, but looking back, this was the best way to begin that process. It was so necessary to engage in deep, long, meaningful conversations before design started.”

After months of deliberation, and close dialogue with Reverend Manning and parishioners, Arad began the design process, a part of his life he still remembers as being “slightly terrifying” for a number of reasons. He had never designed a Christian memorial before and, as a modern architect, iconography and ornamentation weren’t really parts of his design lexicon.

“Iconography is so charged, right? I mean even the word: icon. It distills so much into a symbol,” Arad said. “I paid a great deal of respect to Mother Emanuel’s iconography while trying to use just the right amount so as not to overwhelm the project. We didn’t want to let iconography become the dominating factor. I also wanted to fully reflect the 200-year history of this church, one that goes back way further than what happened in 2015. This place has a long, long history of persecution and perseverance, and community.”

Mother Emanuel’s congregation was formally established in 1791 after a group of free and enslaved Black members left a white-led church to start a new space of worship without discrimination. Then in 1816, Mother Emanuel was founded. Six years later, one of Mother Emanuel’s congregants, Denmark Vesey, planned a slave revolt inspired by the 1791 Haitian Revolution. The uprising was stopped, and 35 people, including Vesey, were executed. Mother Emanuel’s original building was burnt to the ground.

In 1834, Mother Emanuel was rebuilt, at a time when all Black churches were outlawed by the South Carolina state legislature. Mother Emanuel’s congregants met in secret there until the end of the U.S. Civil War. Throughout the 20th century, the building played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. Faith leaders including educator and Civil Rights activist Septima P. Clark and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. each gave moving speeches from Mother Emanuel’s pulpit. The church was included in the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Lee Bennett, Jr., a parishioner and historian of the church, linked the 2015 terrorist attack and Mother Emanuel’s commitment to healing and forgiveness, to the institution’s broader history against injustice. “We lost nine people during that time, but we lost 35 others back in 1822, they were all hung,” Bennett said. “We are a resilient church and we’re going to be around for another 200 years.”

As with myriad tragedies, the 2015 attack inevitably brought people together that, nevertheless, have persevered. Three years after the Mother Emanuel A.M.E. shooting, a white supremacist murdered 11 Jewish worshippers at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue. Afterwards, Reverend Manning reached out to Tree of Life’s Rabbi Jeffrey Myers to offer his condolences, and solidarity.

Since 2018, Reverend Manning and Rabbi Myers have maintained a close friendship, as their friends and families heal. While construction happens in Charleston, Studio Libeskind is designing a memorial in Pittsburgh to honor those lost lives. “All of these tragic events are connected,” Arad continued. “I do think that there are universal truths that we all share which is, you know, loss and mourning; empathy and forgiveness.”

To date, many local politicians and community leaders have helped bring the Emanuel Nine Memorial to fruition. These include Willi Glee, who serves on the Mother Emanuel board of trustees; Scott Parker of the landscape architecture firm DesignWorks; social justice advocate Sandy Tecklenburg; Dr. Brenda Nelson, director of the Mother Emanuel Empowerment Center; and City Councilman Dudley Gregorie.

Construction on the Emanuel Nine Memorial broke ground last summer, but donations are still needed. Phase two of the project to deliver the Survivors’ Garden hasn’t yet broken ground.

For more information, visit the Emanuel Nine Memorial’s website.

Update: This article was amended on April 16, 2024, to include the names of other key actors involved in the Emanuel Nine Memorial which the previous version omitted.