Bernd & Hilla Becher

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 5th Avenue

New York, NY 10028

Open through November 6, 2022

As Reyner Banham recounted in A Concrete Atlantis (his last book, and one sparked by his professorship at SUNY Buffalo from 1976 to 1980), images of factories and grain elevators in the American Midwest proliferated in trade publications that reached architects in Europe who were excited by their “primitivism,” perhaps like the way European artists viewed African art. Some were also collected by Alma Mahler, who sent them back to her lover (and future husband) Walter Gropius, who published them with his own writings. In 1923, Le Corbusier included some of these same snapshots in Vers une architecture, celebrating the silos and factories as “magnificent FIRST FRUITS of the new age.” The next year, Erich Mendelsohn saw and drew the grain elevators of Buffalo, New York. “Everything else so far now seemed to have been shaped interim to my silo dreams,” he wrote to his wife, Louise. “Everything else was mere beginning.”

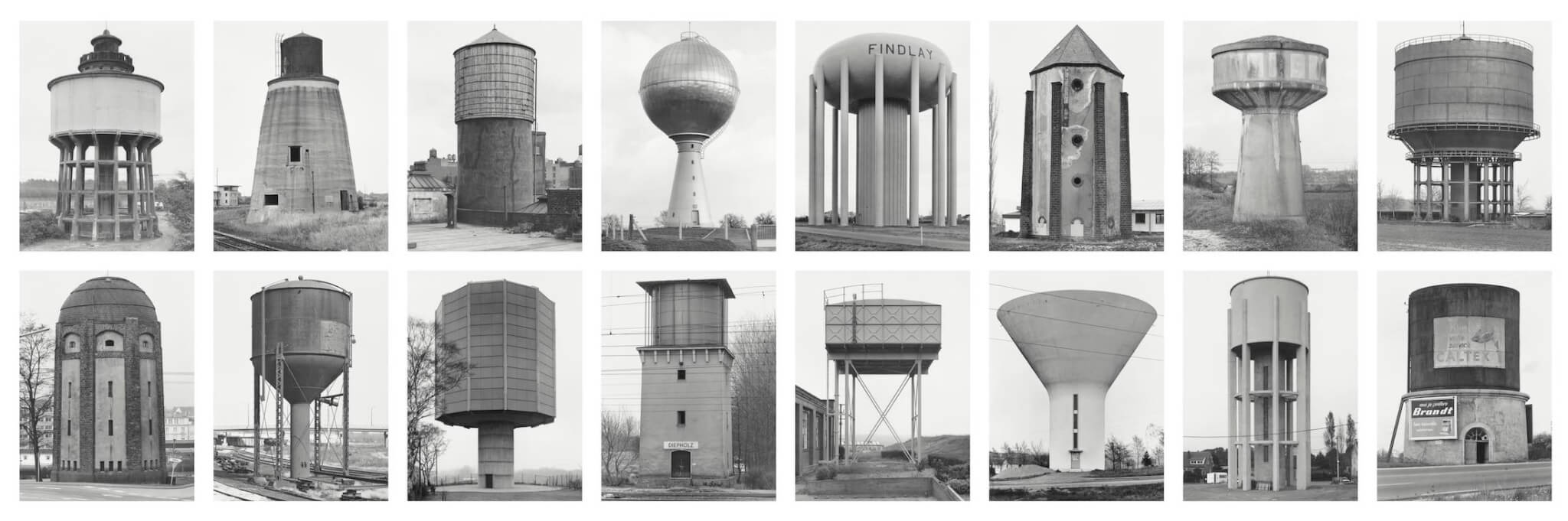

The photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher, now on view at the Met, constitute another such moment of awakening. Bernd died in 2007 and Hilla in 2015, so this exhibition marks the first posthumous retrospective of their practice. Working individually at first and then together for decades, the couple constructed an archive of photographs that documented abandoned industrial sites in Western Europe and the United States. The power of their black-and-white images comes from their precision: Made under overcast skies, they are evenly lit such that each bolt is visible, not lost in shadow or blown out in sunlight. Imaged with expertise, photos made decades apart can be believably ganged together in groupings they called “typologies.”

The Met’s show, which chronicles the Bechers’ full careers from the mid-1960s through the early 2000s, was organized by museum curator Jeff L. Rosenheim with assistance from Virginia McBride and in close consultation with Max Becher, the artists’ son, and Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, director of the Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur in Cologne, Germany, which holds the artists’ archive. The presentation rewards close inspection.

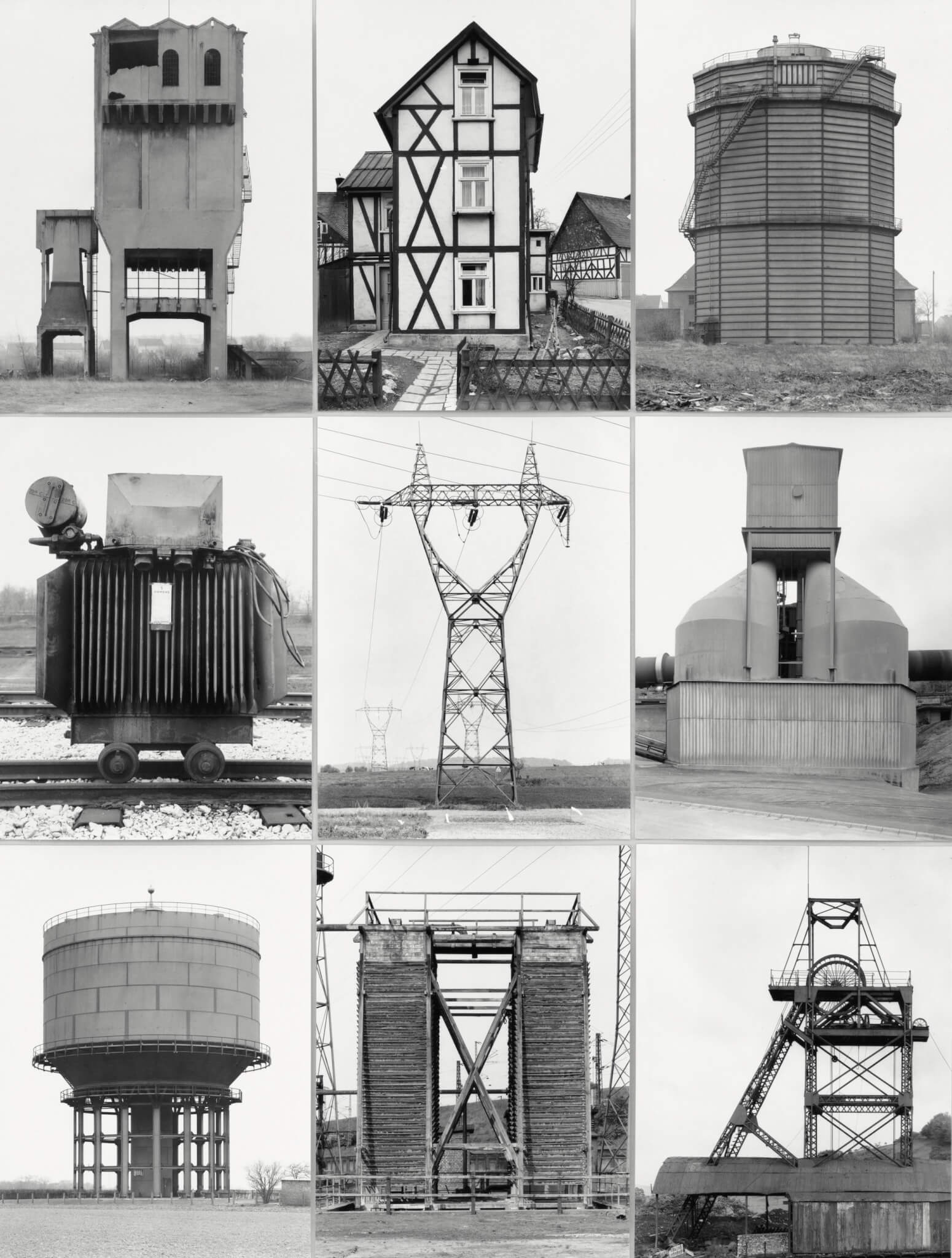

After an introductory staging of “basic forms” (gravel plant, lime kiln, gas tank, coal bunker, etc.), the exhibition begins with the Bechers’ late-1960s project of documenting working-class framework houses in Germany’s South Westphalia. Even then, the couple had found their presentational conceit of gridded groupings; in some sets, the camera rotates around the house as if it were a computer model.

A third room devoted to individual early work realized between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s is revealing, as it documents how the artists brought their own backgrounds to the collaborative project: Bernd as a visual artist long interested in factories, and Hilla as a skilled photographer exploring machine abstractions. The staging establishes their awareness of precedents like Linnaean taxonomy and Ernst Haeckel’s illustrations and showcases the graphic universe of posters advertising early shows. (Bernd and Hilla worked at the same advertising agency in Düsseldorf in the 1950s.) Beyond being selective about when to shoot, the couple also manipulated their surroundings to create their desired foregrounds: A 1987 video made by Max shows them clearing brush at the base of a grain elevator in Ohio to improve their shot.

After two rooms that focus on industrial landscapes generally and the Zeche Concordia mine specifically, the next room demonstrates the link between the Bechers and Conceptual art through staging work by Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre in the middle of the gallery, ringed by some of the Bechers’ greatest hits. Artists of the 1960s were interested in architecture and anonymity. Perhaps the seeds of this interest were sowed in part by Bernard Rudofsky’s influential Architecture Without Architects show, installed at MoMA in 1964; a few years later, the Bechers published their breakthrough book, Anonymous Sculpture. The mixture of ideas—advanced by artists like Dan Graham, Robert Smithson, Andre, LeWitt, and others—linked geologic form to minimal art, while the Bechers captured the industrial processes that produced the materials of modernity.

The final room of typologies is hung in a larger, white-walled gallery. The couple’s popularity stems in part from their consistent bookmaking, so several of their releases are installed here. If viewers have not been previously convinced, this congregation clearly establishes the couple’s mastery. Still, a bit of the era’s machismo lingers: Of the ten photographers shown in William Jenkins’s 1975 New Topographics show, Hilla was the only woman.

In the exhibition’s last room, at least one image comes from Buffalo: a grain elevator (now demolished) that reads H-O OATS. The Bechers made the photo in 1982, after Banham departed SUNY Buffalo but before the publication of A Concrete Atlantis in 1986. Two years later, Roger Conover, then an editor at The MIT Press, invited Banham to pen the foreword to the Bechers’ Water Towers, which introduced their work to American readers; Banham died that year, but his scholarship, notably A Concrete Atlantis, made an impact on the Bechers.

The duo saw their documentation as being for engineers. While viewers are not likely to be knowledgeable about the chemical processes that, when operational, these structures enabled, they will probably be impressed by the contraptions’ geometries. We don’t see the efficient logic of engineering but the “aesthetics of science,” a type of looking that had a pervasive influence in 20th-century architecture. (György Kepes’s books are another example of this vision.) In their sensitivity to combinations of forms—and in the curatorial selection and arrangement of images—the Bechers saw themselves as sculptors and managed their critical reception skillfully enough that when they won the Golden Lion at the 1990 Venice Biennale, it was for sculpture.

The Bechers’ influence can be seen in the establishment of the Düsseldorf School of photography, due to Bernd’s decades of teaching at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, a sensibility later advanced by Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Struth, and Thomas Demand, among others; this lineage isn’t explained in the exhibition, but it’s explored in the accompanying catalog.

While the Bechers’ work changed photography, it also changed architecture. The sensibilities of typological analysis, frontal composition, and “un-authored” plainness can be seen in how architecture is created today. In Epics in the Everyday, architect and writer Jesús Vassallo proposed that “the lifelong trajectory of the Bechers mirrored the process by which European architects of the period confronted their rapidly changing environment” and connected their work to that of Aldo Rossi, who began exploring architectural type in the early 1960s. In 1993, years after a similar line was tossed out in David Byrne’s True Stories, Rossi, writing an introduction to a photography book about grain elevators by Lisa Mahar (who then worked in his office), mused that grain elevators appear like “the cathedrals of our times.” In this century, architectural influence arrived in Philipp Schaerer’s Bildbauten series, in which he constructed fictional elevations from a digital archive of materially rich imagery. (Texts included with its publication by Standpunkte Books, edited by Reto Geiser, established this connection.) Recently, inspiration can be seen in how contemporary architecture is documented and even in the nine-square results of DALL-E, a text-to-image AI, or Midjourney’s surreal assemblies, which generate new forms of anonymous architecture.

What’s missing from the Bechers’ images is, of course, people. Their abstract ruination evidences the global migration of industry; many of their subjects were demolished soon after having their portraits taken, suffusing them with an elegiac quality. The context establishes a postindustrial landscape in which, decades later, a new flavor of conservatism would come bubbling up like oil. The societal neglect that descended following the Bechers’ exposures—that palpable feeling of “being abandoned” known to anyone living in the Rust Belt or South Westphalia—would prove to be a powerful psychological force that has found in politics an outlet for expression. The sobriety of these images invites an encounter with the inevitable entropy of our material constructions. We shouldn’t accept them with complacency. Rather, their funereal calm sets the stage for how we deal with today’s ecological calamities.