Lina Bo Bardi: Material Ideologies

Women in Design and Architecture Publication Series

Edited by Mónica Ponce de León | Princeton University Press | $49.95

Lina Bo Bardi’s journey is a story of personal transformation and translocation. The Italian architect moved to Brazil at the age of 32 and embraced her adoptive country with such openness that she became a Brazilian. Born in Rome, Bo Bardi studied in the city’s school of architecture with Gustavo Giovannoni and Marcello Piacentini, powerful architects under Mussolini. Overwhelmed by the political oppression in Rome, she fled for Milan to begin an architecture practice, but the lack of projects during wartime led her to work at Domus, where she became Deputy Director to Gio Ponti. Early in the 1940s she met the critic, journalist, and art collector Pietro Maria Bardi, whom she would marry in 1946 and move with to Brazil, where Bardi had been invited to establish the Museum of Modern Art in São Paulo (MASP). Leaving the ruins of Milan behind, they sailed to South America where she would encounter an environment of possibility. In São Paulo her first project—the Casa de Vidro, the Glass House—would become her home and studio for the next 40 years. Her modern value system was rooted in Europe, but she was adopted by her new country, taking notes from Brazilian popular culture overlooked by the establishment. Over the course of her career, she would continue to question the establishment and reverse cultural norms.

The architect is the subject of a new book: Lina Bo Bardi: Material Ideologies, the inaugural volume in the Princeton School of Architecture’s student-run Women in Design and Architecture (WDA) Publication Series and the result of the 2018 WDA Conference of the same name. Edited by Princeton Dean Mónica Ponce de León and published by Princeton University Press, it follows recent publications that have brought renewed international attention to Bo Bardi’s work. In her introduction, Ponce de León recalls that while growing up in Caracas she was repeatedly told she could not become an architect, that architecture was a man’s profession. But one day her father told her this was all nonsense and that there was a famous woman practicing architecture in Brazil—it was, of course, Bo Bardi.

The goal of the 2018 conference—and this resulting book, designed by Clanada, Lana Cavar and Natasha Chandani—was to bring Bo Bardi’s legacy into the present and make it relevant for today’s scholars. The twelve writers—a collection of scholars, artists, architects, and curators, including Bo Bardi expert Zeuler R. M. de A. Lima—each provide distinct viewpoints on Bo Bardi’s work, but a few key themes emerge: her unique use of materials, the inclusivity of her projects, nature, and her outsider status. The book includes a generous number of reproductions of Bo Bardi’s sketches, archival and contemporary photographs of her built work, and documentation of the work by the many artist contributors, including photography, film stills, and installation views. Combined, the texts and image sequences deliver an insightful portrait of her pioneering spirit.

Bo Bardi’s aesthetic stood out among modernist practitioners in Brazil and abroad. Her bold use of materials, color, and craft came from her experience of different worldviews. She imported ideas from Italy about what modern living could be, but as she spent more time in Brazil, she invited plurality and difference into her work. The book attempts to explain how Bo Bardi’s respect for local craft and materials distinguished her efforts. Labeling her as “just” a modernist is misleading: As pointed out by Beatriz Colomina in her afterword “Trans-species Architecture,” the “paradox of Lina Bo is that she produced some of the most iconic works of modern architecture, but she also threatens the very idea of modernity and architecture itself.”

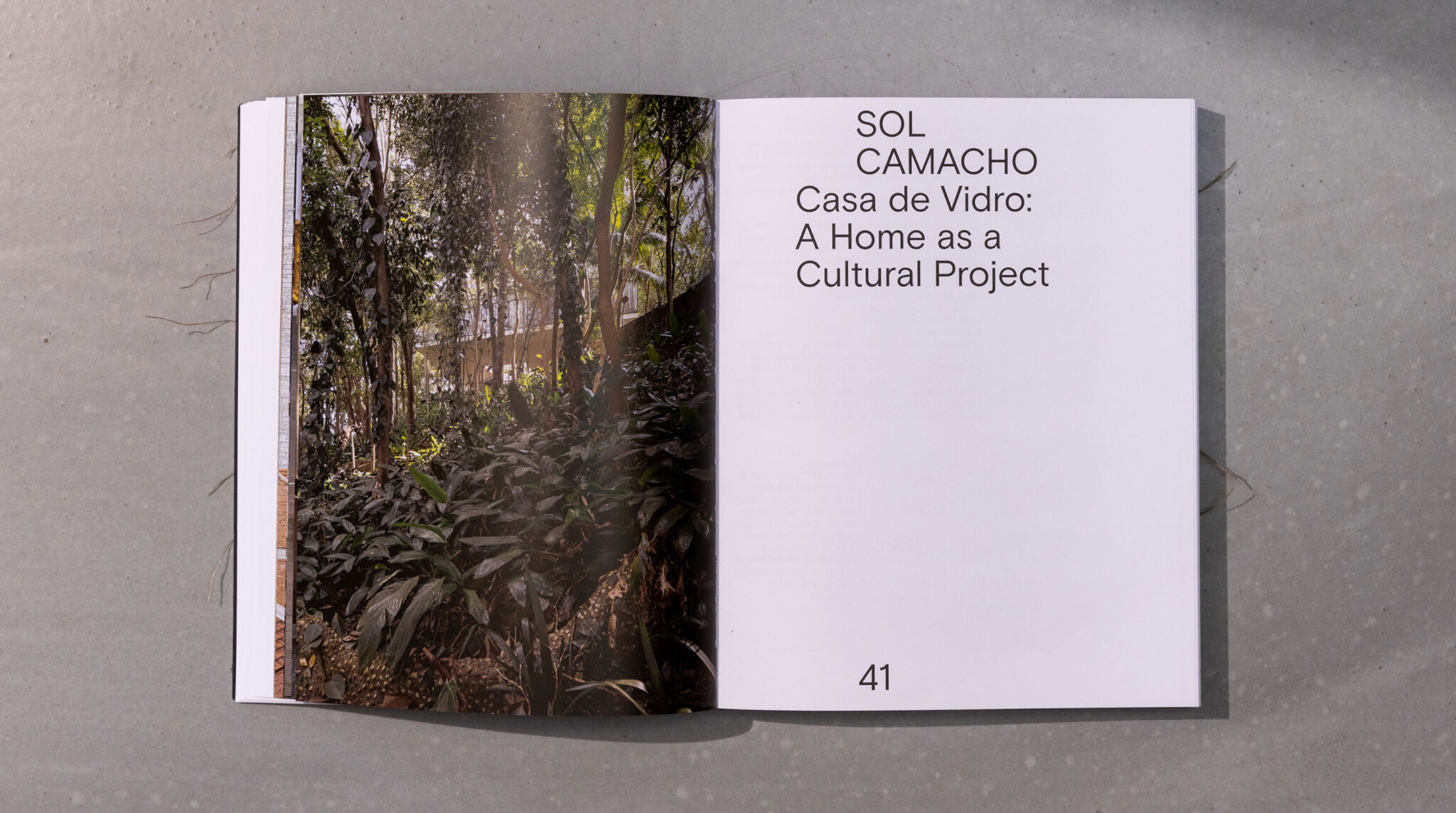

Sol Camacho, the Cultural Director of the Instituto Bardi/Casa de Vidro, reveals that Bo Bardi explored a variety of materials for her Glass House: At one point, the architect entertained wood columns on stone base, a stone stair, and exposed brick instead of the final slender, metallic staircase and whitewashed surfaces. While the Glass House is best known for its public-facing, glazed cantilevered volume, the property consists of several buildings which served as a laboratory to test ideas that would later reappear in other projects, namely brick ovens that reference popular architecture and a garage covered in pebbles and ceramics shards—its green roof and references Antoni Gaudí’s Parc Güell. In the garden wall, Bo Bardi allowed the mortar to overflow, and the Studio (Casinha) has sliding doors reminiscent of Japanese architecture. She incorporated everyday materials—tree trunks, pebbles, plants—into the Cirrell House, which she built nearby in 1958.

Bo Bardi wrote that Brazilian architecture should stem from the simplicity of everyday buildings. In her later works, she rejected bourgeois architecture in favor of modest materials, as would be evident in her reuse of abandoned sites and her work in Salvador, Bahia (like the Solar do Unhão, Casa do Benin, and Restaurante do Coaty), where she used concrete in a more spontaneous way. She wanted to simplify the construction process to reveal the human hand.

The Casa de Vidro serves as a site of material experimentation, and its auxiliary buildings demonstrate how to thoughtfully integrate architecture with nature. Bo Bardi’s devotion to nature had always been evident in her sketches, where she drew plants, animals, and insects with the same level of detail as the people occupying the building. In Habitat—the magazine founded by Bo Bardi and her husband—she wrote that her residence “represents an attempt to arrive at a communion between nature and the natural order of things; [she looks] to respect this natural order, with clarity, and never like the closed house that runs away from the thunderstorm and the rain.” In her later projects she designed porous spaces that integrate the outdoors.

Interestingly, the Casa de Vidro, now surrounded by a lush, tropical forest, was originally built on a cleared site. Jardim Morumbi, where the house is located, was a former tea farm, and the prior occupants had razed the native Atlantic Rainforest. Contributor Veronika Kellndorfer, who photographed Casa de Vidro as part of a beautiful ethereal series called Cinematic Framing, insightfully points out that the house began as a frame for the landscape, which eventually subsumes it, and so the garden goes from being the background to becoming the main character.

Bo Bardi’s architecture was all-inclusive, open to animals and insects as well as to adults and children, but in particular it invited those typically excluded from elitist institutions. In her view, human life should always be the protagonist of architecture. Her greatest civic project is MASP, built in 1968, where, in her words, she “sought a simple architecture, an architecture that could immediately communicate what, in the past, was called ‘monumental,’ that is, the sense of ‘collective,’ of ‘civic dignity.’” Her radical design for crystal easels—with every painting mounted to a glass easel, not a wall—encourages free, non-regimented exploration of the galleries. Bo Bardi, together with the museum director (her husband Pietro), wanted to “change the museum visitor demographic, increase the population of art viewers, and fundamentally change what was considered valuable and worthy of display in an art museum,” Cathrine Veikos wrote. The volume of the exhibition hall hovers above a void that serves as a public square, host to fashion shows, dance classes, music and art classes, and crowds of children. Most recently, it was one site of celebration after the election of Lula as the next president of Brazil.

Perhaps Bo Bardi’s desire to create inclusive spaces stemmed from her own outsider status as a foreigner and a woman working in a male-dominated field. That her work could not be neatly categorized and that her career spanned a wide range of fields also contributed to her distributed legacy. Beyond her work as an architect, she was also an artist, activist, editor, designer, and writer. Contributor Jane Hall argues that Bo Bardi’s marginal status enabled her prolific output, giving her the freedom and confidence to build as she did.

Why are we so drawn to Bo Bardi’s work today? Maybe it’s because she forged her own path and anticipated trends and sensibilities that are now central to contemporary architecture discourse: We regularly center material sensitivities, defer to context, and prioritize the valuation of plant life, gender, class, race, and interspecies relationships. It is precisely the complexity of her character that allows for deeper readings of her work. Colomina points out that Bo Bardi is missing from modern architecture’s canonical histories, and that this erasure has liberated her. Lina Bo Bardi bewildered history’s authors, Colomina wrote, because she “doesn’t fit their narrow moralistic stories. She breaks free. She confuses the discipline. She opens new questions and keeps opening them because the reading of the work is only just beginning. For all the sudden celebrations in books, catalogs, exhibitions, films, etc. of the last 20 years, Lina Bo still surprises. Perhaps because what she really challenges is architecture itself.”

Letícia Wouk Almino is an architect and artist based in Brooklyn, New York.