How to Build a Low-Carbon Home

Design Museum London

Through March 2024

To grind down limestone and heat it with clay, to mine iron ore and power blast furnaces, and to fire kilns—the everyday processes of manufacturing building materials like concrete, steel, and brick—emits huge amounts of carbon dioxide. Yet contemporary construction industries rely heavily on these basic processes. When we talk about embodied carbon in architecture, we mean emissions associated with the extraction, manufacture, transport, assembly, maintenance, replacement, and disposal of all materials that make up a building. These alone account for over 9 percent of global carbon emissions.

The urgency of this may at first feel overwhelming or only surmountable through innovating wholly new ways of building. However, many of the tools we need have existed for millennia: Returning to time-honored processes that center natural materials—such as timber construction, thatching, and stonemasonry—is the key to a low-carbon future.

These concepts are on full display at the Design Museum in London. Curated by Esme Hawes and George Kafka, How to Build a Low-Carbon Home is full of architects and their drawings, tools, scale models, and building materials—but this exhibition is not just for architects. It is an accessible and instructive guide for anyone, showing a new path forward for home-building during the climate emergency. The exhibition is anchored by three London architecture practices that are spearheading the use of natural materials: Material Cultures represents straw; Waugh Thistleton, wood; and Groupwork is stone. The exhibition forms part of a broader research project on low-carbon housing led by Dr. Ruth Lang and the Design Museum’s Future Observatory.

The first material investigation approaches mass timber by starting with the importance of sustainable timber production and forest management. Trees sequester carbon as they grow, but when they die, it is released back into the atmosphere. Building with timber stores this carbon, while planting new trees sequesters more: This is the carbon cycle, and it can facilitate carbon-negative construction. The evolution of engineered timber—layers of raw wood veneers, fibers, or particles bound together—promises to deliver on much of what steel and concrete can. This Waugh Thistleton proves in its work. Fragments of engineered timber plainly show the differences between cross-, dowel-, and glue-laminated timber (CLT, DLT, and glulam), while images of Waugh Thistleton’s mixed-use Dalston Works in London show these methods implemented in the construction of the world’s largest CLT building (10 stories tall). The intimate details of the material are contrasted with its change-making possibilities to show the potential of timber construction for both the self-builder and the large-scale developer.

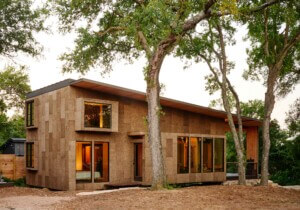

The next material on view is straw, still suffering from a ruined reputation thanks to three little pigs and a big bad wolf. This display, drawing on the rigorous work of Material Cultures, debunks these myths. Straw here is a broad term that refers to the stalks of cereal plants, but its resurgence as a building material is due to developments that involve combining it with earth, clay, bio-resins, or lime to make walls, bricks and insulation. Straw is fast-growing and already a natural by-product of grain production. New architectural processes therefore harness this intrinsically untapped potential. The building components made with it are usually air-dried, making it a low-carbon process by avoiding heat-intensive fossil fuel combustion. The beautiful potential of the material is made more visually clear in this exhibition thanks to photography by Oscar Proktor: A new series showcases the walls of Flat House by Material Culture, constructed from timber cassettes filled with a mulch of hemp, lime, and water.

Finally, the stone-focused display shifts gears in terms of technique: Handheld processes replace the loud, invasive ones we usually envision when considering stone. A wire embedded with diamond beads is displayed next to a film by Joseph Bushell that visually describes how something so small and simple can cut through solid rock. A geological map of the U.K. illustrates the makeup of its bedrock and how this has influenced the vernacular. Surrounded by stone samples, the map then illustrates each stone’s material quality and even color, shifting from the burgundy of St. Bees stone to the ashen gray of Clipsham stone. A compelling argument is also made here for the extraction of stone. Unlike concrete and steel, the raw material is construction-ready upon extraction, requiring no intensive post-processing. The display concludes with the end of the material’s life cycle: the end of the quarry. Quarries can be remediated back to more healthy, natural states, as with the Centre for Alternative Technology in rural Wales, if not completely redeveloped, like Craigleith Quarry in Edinburgh.

So, how can all of this combine into the home proposed in the exhibition’s title? A propositional model by Webb Yates Engineers shows what such a structure could look like. Made with just the materials on display (wood, straw, and stone), it proves the structural possibilities but also displays their charming qualities. Travertine marble is the primary structure, while Douglas fir is used for timber beams. Straw, represented in the model by grass, provides insulation and roofing.

The display shows exceptional work by architects, but it ends with the insistence that projects and practices like these should not be the exception. The wall text asserts the need “to increase the local supply of these materials and train a new generation of skilled construction workers to build with them.” So, How to Build a Low-Carbon Home reminds that we must consider people, labor, and collaboration in addition to materials when building our low-carbon future.

Ellen Peirson is an architectural designer, writer, and editor based in London.