Demolition is underway on one of the few East Coast buildings designed by the late Anthony Lumsden, a colleague of Cesar Pelli and former member of the “LA 12,” a group of California-based modernist architects. Contractors are taking down the Bard Building, a five-story structure that Lumsden designed for Baltimore City Community College when he was director of design for Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Mendenhall (DMJM).

Named after the college’s founder and first president, Harry Bard, the 172,642-square-foot Bard Building at Lombard Street and Market Place was designed to contain classrooms, a library, a fashion design studio, student lounge, and faculty offices.

It opened in 1976 as part of a two-building satellite campus for the community college, whose main campus is on Liberty Heights Avenue in West Baltimore. A smaller companion structure also designed by Lumsden, the two-story William V. Lockwood Building, opened the same year as part of an effort by the college to establish a presence near the city’s rejuvenated Inner Harbor and downtown workforce.

In recent years, the college has concentrated its programs in West Baltimore, allowing the Lockwood property to be cleared and redeveloped in the 1990s and shuttering the Bard Building in 2009. Fenced off and in poor condition, the one-time symbol of the college’s growth came to be seen as an eyesore at a busy intersection one block from the waterfront.

The college, which owns the 1.1-acre site, has explored the idea of maintaining a downtown presence, possibly by building a mixed-use structure there in partnership with a private developer, but a replacement project has not materialized.

Last summer, Maryland Governor Wes Moore and other members of the state’s Board of Public Works granted a request to spend $4.2 million for the Bard Building to be razed. The state’s plan is for the building to be replaced temporarily with a “green space” to give campus leaders time to come up with a plan to guide future redevelopment of the property.

State officials say the college has begun a community outreach effort as part of a long-range planning process and that demolishing the building now will eliminate an eyesore and potential safety hazard, while making it easier for eventual redevelopment later.

In the 14 years since the college ceased operations there, “this building has fallen into significant disrepair,” Moore said during the state Board of Public Works meeting at which demolition funds were approved. “So today this board is taking a critical step to be able to finally demolish the vacant building” and work with college leaders to think about “the future of that site and what it’s going to mean not just for [the college] but also what it’s going to mean for Baltimore as a whole.”

Because of its deteriorated condition, “it’s very clear that the building needs to be demolished,” college president Debra McCurdy said at the meeting. “We just can’t be more thrilled to move forward and then to begin to introduce to this community…the larger vision of what could happen in the old Bard site.”

Big-name Architects

Baltimore City Community College hired Lumsden and DMJM at a time when public officials and private developers were looking for big-name architects from out-of-town to design buildings around Baltimore’s revitalized waterfront.

One of Baltimore’s former housing commissioners was an architecture aficionado who kept a wish list of prominent architects he’d like to see design buildings for the city’s skyline, and he landed many of them. Others enlisted to design buildings in downtown Baltimore included Henry Cobb for the World Trade Center Baltimore, Edward Durell Stone for the Maryland Science Center, and Benjamin Thompson & Associates for the Harborplace pavilions.

Other starchitects who designed major projects for downtown Baltimore that were never realized include Kenzo Tange, Louis Kahn, Richard Rogers, Philip Johnson, Kevin Roche, and Michael Graves.

DMJM was reorganized in 2000, and its architecture offices became part of the AECOM design network. Lumsden left DMJM in 1993 and opened his own practice, Anthony J. Lumsden Associates. He died of pancreatic cancer in 2011 at the age of 83. The Bard and Lockwood buildings were his only two buildings in Baltimore, apart from the subway system.

A number of Lumsden’s projects remained unbuilt, including his 1973 design for a Beverly Hills hotel, which would have included a series of cylindrical guest room wings extending from a central tower, all mirrored in glass. Others were later used as sets or backdrops for films and television shows, including his Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant, which doubled as home of the Starfleet Academy in the motion picture series Star Trek: The Next Generation. In 1976, Lumsden was named one of the “LA 12,” a group of distinguished architects based in California, along with Pelli; Frank Gehry; John Lautner; Craig Elwood and others.

Tiles Falling Off

The Bard Building wasn’t as well received as some of the other structures taking shape around the harbor. One adjective frequently used to describe it was “hulking.” Phoebe Stanton, the architecture critic for The Baltimore Sun when it opened, gave it a scathing review.

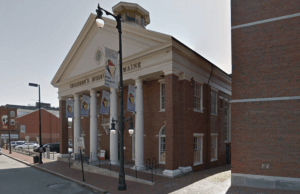

One criticism of the Bard Building was that its main entrance was dark and foreboding, with a steep flight of stairs that posed a barrier to people in wheelchairs. The exterior was clad in red ceramic tiles that had not been used before locally. They were Lumsden’s response to the traditional red brick used on nearby structures such as the Candler Building and the Wholesale Fish Market, now the Port Discovery children’s museum.

The building’s exterior didn’t weather well. While its ceramic tiles may have been suitable for the climate of Southern California, in Baltimore they began cracking and falling off the side of the building, causing leaks inside. Engineers brought in to assess the situation said Lumsden and his associates didn’t take into account the freeze-thaw cycles common with East Coast winters.

The tiles expanded and contracted at a different rate than the concrete structure to which they were attached, and that caused them to break off. At one point campus planners reskinned the top floors with a champagne-colored material that gave the building a two-tone look, as if it were wearing a helmet.

The fate of the Bard Building matches that of other modernist structures torn down in Baltimore over the past decade, among these the Morris A. Mechanic Theatre by John Johansen, demolished to make way for a high-rise apartment project that never materialized; the McKeldin Fountain, a Brutalist sculpture and fountain by Thomas Todd of Wallace Roberts & Todd, replaced with a plaza; and the Mattin Center, an arts center on the Johns Hopkins University’s Homewood campus by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects. Mattin Center will be replaced by a student center designed by BIG, Shepley Bulfinch, Rockwell Group, and others.

Last fall, the development team that controls the Harborplace pavilions disclosed plans to tear them down to make way for a mixed-use development containing 900 apartments, offices, shops, restaurants and public space, with buildings. Before that project can move ahead, an amendment to the City Charter must be approved by local voters in a referendum that will be placed on the ballot in November of 2024.

Demolition of Lumsden’s Bard Building and completion of the green space is expected to take about a year.