Vincent Scully: Architecture, Urbanism, and a Life in Search of Community by A. Krista Sykes | Bloomsbury | $115

In 1983, a stereotypically professorial man—60-something, ruddy complexion, tweed blazer—led public television audiences on a leisurely two-hour stroll through a history of American art. New World Visions: American Art and the Metropolitan Museum, 1650–1914 began in the galleries of the famed New York museum but often cut away to significant locations beyond the gallery walls. There, the genial, polymathic host waxed poetic over architectural achievements in Manhattan’s financial district, sleek rowing sculls in Philadelphia, faint battle scars still etched into the landscape at Gettysburg, and the noble Neoclassicism of the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

By the time the two-part special aired on PBS, the host was widely celebrated in academic and cultural circles. Eight years earlier, People magazine had declared him one of “12 Great U.S. Professors.” Nine years before that, he had graced the cover of Time magazine as one of ten “Great Teachers.” And roughly a decade after the release of New World Visions, my own sister, who, near as I could tell, was majoring in Jimmy Buffett at the University of Miami and never once displayed an interest in architecture, found herself captivated by a gifted professor she still affectionately refers to as “Vince.”

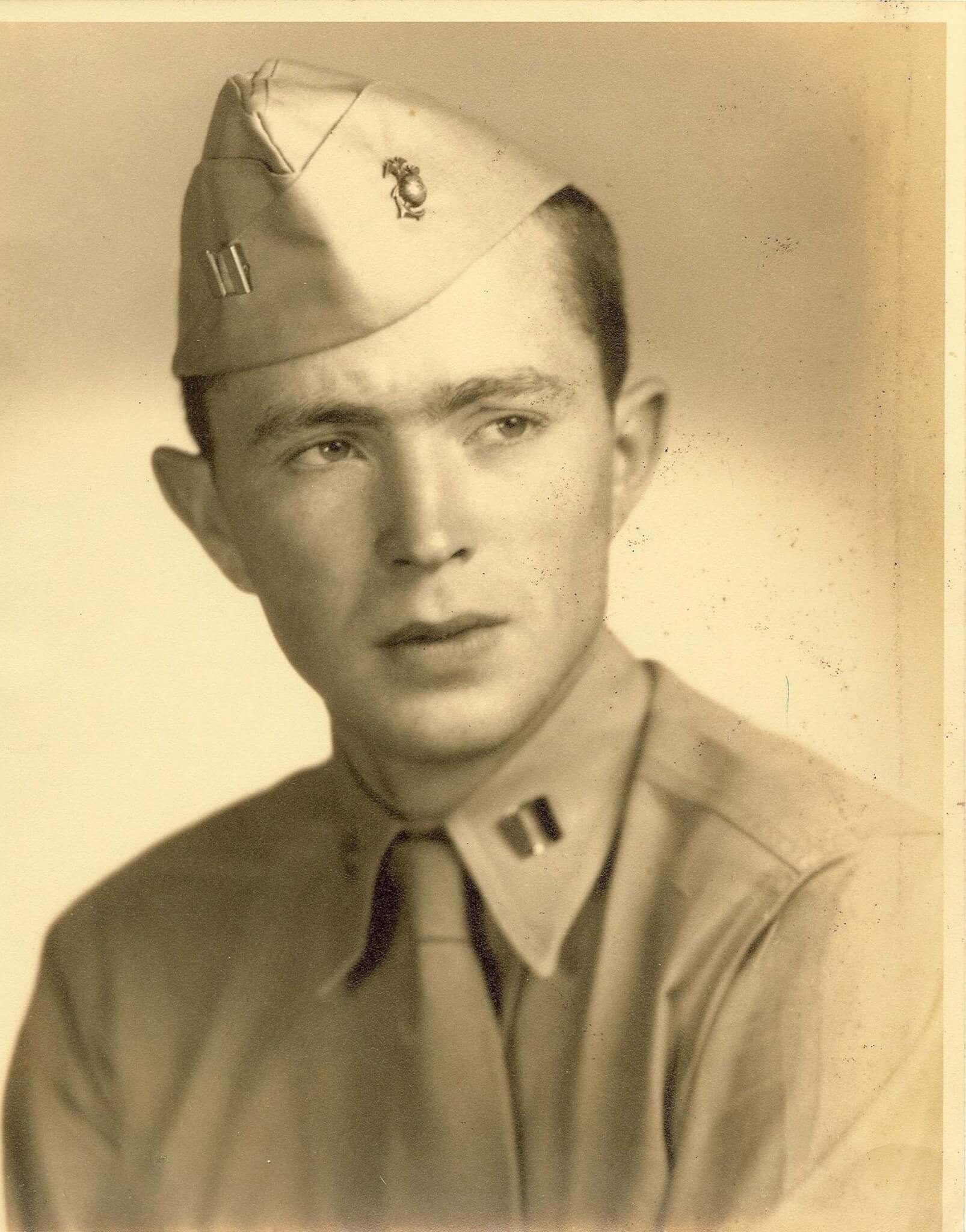

Just how Vincent J. Scully, Jr. (1920–2017) rose to such heights of academic celebrity is the subject of A. Krista Sykes’s intelligently researched and smartly written biography, Vincent Scully: Architecture, Urbanism, and a Life in Search of Community (Bloomsbury, 2023), in which Sykes traces Scully’s life from his childhood in New Haven, Connecticut, through his school days at Yale, his military service during World War II, and his rapid rise to fame in postwar academia.

As Sykes recounts, Scully was born an only child to a working-class family. A precocious student and voracious reader, he won early admission to Yale, where he helped pay his way by serving meals to his well-heeled classmates. The war years left Scully with a new wife, a young family, and psychological wounds that plagued him for the rest of his life. He sought solace in the study of art history at Yale, and soon fell under the sway of Henry-Russell Hitchcock, whose 1932 book The International Style: Architecture Since 1922, coauthored with Philip Johnson to accompany their groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, had introduced mainstream American audiences to European modern architecture.

Studying design at the Yale School of Architecture alongside his coursework in art history, Scully was trained in an environment largely convinced of the rightness of European modernism. However, as his mentor Hitchcock had done, he soon turned his attention to the earlier work of Frank Lloyd Wright and then to American architecture more generally, eventually producing a dissertation on the American cottage style of the 19th century. Reworked for publication as The Shingle Style: Architectural Theory and Design from Richardson to the Origins of Wright (1955), Scully’s research was well received and helped secure his place on the Yale faculty, even as some critics chastised the “extravagant phraseology” and “near evangelical furor” of his lively prose.

That unbridled enthusiasm for his subject matter became a hallmark of Scully’s famous lectures on the history of art and modern architecture. He brought a similar enthusiasm to later works on an almost irresponsibly broad range of topics. He followed The Shingle Style with monographic studies of Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn, surveys of modern architecture and American urbanism, analyses of sacred sites in ancient Greece and the American Southwest, a treatment of Andrea Palladio’s villas, and a sweeping presentation of the relationship of built form to the surrounding landscape in his last major book, Architecture: The Natural and the Manmade, in 1991.

Sykes traces these investigations alongside Scully’s development of his celebrated courses at Yale and his increasingly influential voice in both contemporary architecture and historic preservation. These efforts cemented his reputation on the world stage even as his willingness to wander into neighboring academic fields sometimes drew harsh criticism. The drubbing he received from archaeologists who reviewed The Earth, the Temple, and the Gods (1962), for example, stung him deeply and likely moved him to cancel a planned sequel to his study of Greek sacred architecture. Even so, in Sykes’s Churchillian phrasing, “Scully’s driving conviction [was] that architecture and society share a give-and-take relationship—society shapes and is shaped by the architecture it creates.”

At the same time, Scully shaped and was shaped by the architectural and political culture around him. His early enthusiasm for the work of his friend Robert Venturi led him to proclaim the architect’s now-canonical book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) “probably the most important writing on the making of architecture since Le Corbusier’s Vers une Architecture, of 1923.” The claim seemed outlandish when it first appeared; with time, it proved eerily prescient. Scully’s advocacy of Venturi’s work helped create a receptive context for the architect’s iconoclastic ideas, just as his support of Robert A. M. Stern and the so-called “gray” architects of the 1970s helped set the tone for the discourse on postmodern architecture in the United States.

After retirement from Yale, Scully took a visiting position at the University of Miami in Florida, which placed him in close contact with his former students Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, key players in the development of the New Urbanism. He spent many of his remaining years advocating for (and occasionally criticizing) New Urbanism’s “architecture of community,” which embraced the American vernacular he had studied in his youth and the small-town feel of places like his beloved New Haven, which remained dear to him to the end.

Drawing on interviews she conducted with Scully during his lifetime, unprecedented access to his personal papers, and a deep familiarity with the architectural culture of the 20th century, Sykes treats these and other episodes in Scully’s long career with intelligence, compassion, and admirable clarity. Anyone interested in the historian’s life and work or in the development of American architecture from the postwar period to the present will find much of value here, though some specialized readers may wish for closer analysis of Scully’s texts or more contextualization of his work with that of his peers.

While Sykes briefly examines Scully’s relationship with Colin Rowe and Reyner Banham, for example, a more sustained comparison with these two close contemporaries could be of interest. And though his friend and Yale colleague Harold Bloom figures strongly, I waited in vain for a discussion of Scully’s connection to the theory hothouse that burgeoned at Yale in the 1970s: One of the aims of deconstruction as developed by the so-called “Yale Critics” (Bloom, Paul de Man, Geoffrey Hartman, and J. Hillis Miller) was to destabilize exactly the sort of grand narratives the historian elaborated throughout his career.

Sykes, who previously assembled two informative anthologies of architectural theory, surely knows this, just as she knows that the sort of meticulous close reading such an analysis would require would run counter to her broader ambitions here. For in the end, Vincent Scully is a work of biography, not historiography. Sykes exhibits a preference for clear vistas across the narrative forest over scrutiny of individual trees. I suspect she does so in deference to intelligent general readers, like my sister and the countless students from outside the architectural ken who sat rapt in Scully’s lectures. As is the case with Scully’s texts, Sykes’s engaging style and first-person involvement does not detract from her scholarly achievement. Rather, it offers a laudable model for contemporary scholars looking to expand the reach of their efforts and a valuable portrait of one of the most important American architectural historians of the 20th century.

Todd Gannon is a professor of architecture at the Ohio State University.