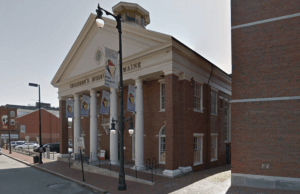

Bedridden with COVID last Monday, I had the opportunity to check in on the live online broadcast of the PHI Contemporary International Architecture Competition, wherein five architecture teams presented their design schemes for a new contemporary art space embedded into a complex heritage site in Old Montreal. The project, initiated and financed by cultural entrepreneur and philanthropist Phoebe Greenberg, will be the institution’s third location in the city, extending PHI’s cultural offerings, which are currently provided by two other venues: PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art and PHI Centre. The new 74,000-square-foot project will include room for exhibitions, a network of new media galleries, research and studio facilities, as well as new open spaces accessible to the public.

In between coughs and cups of tea, I managed to hook my phone to my flat screen and started watching. What a treat! In a strictly timed event, five teams presented their design concepts and spatial solutions for the new contemporary art space. Of course, I was engaged. (I have to confess, I was personally involved to a certain degree. With my design firm PRODUCTORA, I had, several months earlier, responded to the “call for candidature” published by PHI. I had read the brief with care and had established my own take on the preservation problematic and the institutional ambitions expressed therein. We even submitted a design vision. Unfortunately, we were not selected.)

In November 2021, PHI Contemporary selected a shortlist of ten firms (or teams). They were mostly Europeans, with the exception of the Montreal-based in situ atelier d’architecture, the New York firm SO-IL, and the Chilean architect Smiljan Radic. The team consisting of Montreal’s Pelletier de Fontenay and Berlin’s Kuehn-Malvezzi was the only joint venture, as previous mutual experiences in Canada was a requirement for collaborations; they had just delivered the Montreal Insectarium together. After a first round of proposals, the selection was reduced from ten to five participants.

During the online event, the five firms showed videos and slideshows to illustrate the general ideas of their buildings. After each presentation, the architects were questioned by a strong and diverse jury including Amale Andraos of WORKac; artist Miles Greenberg; PHI Founding Director and CCO Phoebe Greenberg; Jacques Lachapelle, a professor at Université de Montréal; architect and curator Ippolito Pestellini; artist Jean Michel Othoniel; and Dan Stubbergaard of Cobe. Questions ranged from technical-administrative issues (such as the local urban restrictions, ADA accessibility, or costs of excavations) to broader questions related to the problematic colonial history of Montreal and how the architects could respond to the city’s socio-historical issues.

While enjoying the live transmission in which myriad perspectives on the design task were presented openly, I couldn’t stop thinking of a press release circulated by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in March. The announcement stated that the Mexican architect Frida Escobedo had won the competition for a $500 million renovation of the Met’s modern and contemporary galleries. The news came as a bit of a surprise because in 2015, the Met had announced that its new wing (a pursuit more than a decade in the making) would be designed by David Chipperfield. Now—after some internal movements within museum leadership, including changes of director and revised financing strategies—the Met had organized a new competition that invited five firms to present new ideas for the museum extension.

The list was certainly exciting. First there was David Chipperfield again, who, although more conservative, is undoubtedly one of the most talented and sensible designers with an impressive track record intervening in historic buildings. Then there was SO-IL, a progressive New York firm that just recently finished the beautiful Amant Foundation in Brooklyn. From Spain, there was Ensemble Estudio, whose radical assemblages have produced astounding poetic structures. From France, there was Lacaton & Vassal, the 2021 Pritzker laureates who make groundbreaking work centered on economy of means, value engineering, energy efficiency, and, often, the improvement of subsidized housing. (I found it hard to imagine the socialist-minded Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal—accustomed to dealing with city planners and bureaucrats—addressing the board members of the Met.) The fifth and last candidate was Frida Escobedo, a talented colleague from Mexico City who managed to incline the jury towards her firm’s proposal.

Just like in 2015, when Chipperfield was declared the architect for the new wing, the museum didn’t reveal a single image from its chosen proposal. The press release mentioned that Escobedo’s design will “create an enduring space for art while reconciling the wing’s relationship with the existing building and park,” that it “draws from multiple cultural narratives, values local resources, and addresses the urgent socioeconomic inequities and environmental crises that define our time,” and that it will be “a vibrant, exhilarating space.” So, not much there. I cannot stop thinking what a missed opportunity it was to exclude the public from a view into the competition proposals and the selection procedure. The enormous efforts undertaken by these five world-class design firms, each presenting different views on how a public-private institution like the Met can engage with the public realm and Central Park, will never see the light of day due to highly restrictive non-disclosure agreements.

The public debate that such an emblematic project could bring about is effectively silenced by boardroom secrecies and internal high-brow politics. Since the Met is in the end both a private and public institution (mostly funded by private money, but in a building owned by New York City, and thus supported by taxpayer dollars), does the general public have a certain right to an insight into what these design proposals are about? Shouldn’t the Met, which likes to present itself as an enlightened institution serving the city and public, not invite broader debate on cultural institutions, architecture, and the city? When I asked my New York colleagues about this missed opportunity to make these competition entrees (and maybe even the jury process) public, I only got evasive comments, essentially saying “that is not the way things work here.” Well, alright. Who am I to question the current state of affairs? Yet, a voice inside asks: If we believe that architecture is a public practice and a discursive cultural profession, then shouldn’t public debate be encouraged? Shouldn’t we call out missed opportunities and point out where lessons can be learned?

I recommend looking at the website of the PHI Contemporary architecture competition. There one can follow in detail the schedule and unfolding of the competition, understand the institutional ambitions, and review the composition of the jury. Although no project images are shown until the final resolution of the procedure (which I completely support as I object to public interference in the selection process through populist voting or harmful commenting processes), the general audience was invited to attend the design presentations in-person or online. The website even offers insight into how much each firm is paid in each phase of the selection procedure. If, in Montreal, Phoebe Greenberg aims to “create an open space dedicated to probing the most relevant ideas of our time through its invitation to the public,” then this competition procedure is certainly a first step in the right direction.

Wonne Ickx is a co-founder and partner at PRODUCTORA. He lives in New York City.