These days, it’s quite common for architects to consider issues of equity and inclusivity in the built environment, not to mention fair labor practices in their offices as well as on construction sites where their projects are built. Such important issues are now part of the discipline’s standard discourse, from the academy to the AIA.

But it wasn’t always so. Mike Davis, the much-lauded writer, urban theorist, and historian who died on October 25, was a major force in opening architecture’s eyes to the often-disastrous results of its output on public space. Through his many books, including City of Quartz (1990), Ecology of Fear (1998), and Planet of Slums (2005), as well as through his teaching at SCI-Arc and other institutions, Davis helped to bend the profession from the esoteric formal disputes of the postmodern period toward the realm of social and environmental responsibility that now reigns. Though his work focused mainly on Southern California, most notably Los Angeles, the implications of his scholarship and analysis are wide ranging. He had a tendency to go straight to where the trouble and injustice were the greatest (like New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, for example, where he filed his sole piece for our publication). I don’t think it’s going too far to say that he was instrumental in giving architecture a conscience.

On the occasion of his death, AN gathered remembrances and tributes from a range voices in the profession, academy, and beyond. We collect them here. —Aaron Seward, editor in chief of The Architect’s Newspaper

Orhan Ayyüce, educator, architect, editor, and writer

I feel fortunate to have met Mike Davis and spent a whole day visiting the places he selected. It was like shortcuts of urban stories around San Diego. After picking me up with his truck from Greyhound station, we drove to El Cajon, where he was born. We stopped by Hells Angels Dago quarters and by the Unarius Academy of Science, where cult members built a large circular model of a city in which they will survive doomsday. We sat down for lunch at an Iraqi restaurant where U.S. Marines recruited Arabic-English translators for the ongoing petrowar in Mesopotamia. Next, we drove into San Diego’s early history when the developers sold large homes and the nouveau riche etiquettes to farmers. The real estate barons imported a British quasi-music composer who was also an ouija board master with the task of creating an instant aristocracy. Finally, we went to a site of resistance, Chicano Park in Barrio Logan. We were talking nonstop this whole time.

In his house, I notice a small bookshelf filled with infrastructural research books from the more service-minded era of American municipalities. I remember he was a methodical researcher feeding his imaginative writing with serious papers.

Saying goodbye, he told me next time he would take me to scorched hills where crowds rev up their ATVs to fulfill their road warrior fantasies.

Back in L.A., it felt good to know Mike Davis this way. I am grateful for his creative soul, humanity, and speaking for the working classes internationally.

He left us with his priceless work. Thank you, Mike Davis.

Aaron Betsky, professor, School of Architecture and Design at Virginia Tech

Mike Davis was my guide to Southern California, whether it was in person—driving through the San Diego backcountry, listening to him describe the communities and landscapes he had become part of while driving a truck there before he became an academic; crossing the border from there into the informal settlements east of Tijuana; venturing into the tunnel just west of downtown Los Angeles that I knew from so many movies but had never realized existed was the home for a shifting group of outlaws, homeless, and taggers; or finding what was left of the utopian settlement of Llano del Rio (very little)—or reading his books and listening to his talks, a geography that both was real in all its grit and contrasts and went beyond what I could see with my eyes opened up.

Davis’s California was a mythic place, wracked by class struggle and climatological upheavals as present as any battle for Troy or invasion of orcs. He fought in those conflicts as well with his body and his words, walking picket lines and getting himself arrested for the cause. Some thought he was a prophet because he pointed out that events such as the 1992 civil unrest or the Malibu fires a few years later were bound to happen. For those of us who were there, he merely gave voice to the forces for both good and evil that were making California and appeared in daylight and media light only during those upheavals. That he did so with images that still are true after decades is a tribute not only to his immense talent, but also the power of the place that was his scene.

Christopher Brown, author of Tropic of Kansas and The Secret History of Empty Lots (forthcoming)

I first discovered Mike Davis on the New Releases shelf of a branch library in the late 90s, as a free-foraging young science fiction writer looking for fresh brain bombs. The book was Ecology of Fear, and I may have thought it was a novel at first. But it was something entirely new—a kind of dystopian nonfiction, synthesizing everything from disaster movies to geology and radical political economy to make you see the way the city really works. A book that saw the worst things about the way humans inhabit our environment through the prism of Anthropocene ecology, long before we even had that term. When I got to see him in person years later, he mentioned in passing how every few years he took a sabbatical to work as a union truck driver. That’s when I learned to appreciate the rare moral integrity and sense of justice that was what really made his work stand out among the endless shelves of smart works of theory and criticism.

Anthony Carfello, editor and project manager

“City of Quartz at 25” was a frustrating panel I attended at Occidental College in 2015. A cross-section of boosters took turns smugly emphasizing that the utility of Mike Davis’s book was in past tense and that “Fortress L.A.” was inapplicable to the early Garcetti era’s supposedly genteel gentrification. I still wonder which exact sanitized and financialized corners of this city these Southland scholars—including the former L.A. Times architecture critic—had in mind when sharing their understanding of L.A. What did they think had changed really? The new forms of the same inequalities that City of Quartz (and Ecology of Fear) had described so presciently were everywhere to be seen. More surveillance, more money, more fences. Were the participants not around in 2011 when City Hall was occupied and Davis was writing about the 1% as the powerful downtown aliens of John Carpenter’s They Live? Davis had known not to attend that night. Five years later, however, Davis did join other discussions with leaders across social uprisings, while the moderator of the aforementioned panel was, by then, working at City Hall with the failed mayor.

One enters and exits life in the movement in the middle of the work. Davis is the “red godfather” that others once were to him, and those newly reading him right now will become the same in the future.

Matthew Coolidge, director of the Center for Land Use Interpretation

Mike Davis was making Los Angeles more interesting right around the time the Center for Land Use Interpretation moved down from the Bay Area in the 1990s. With earthquakes, riots, and other disasters, Los Angeles felt like it was the center of the future, and Mike its chief interpreter. He confirmed suspicions, while widening the field of possibilities, making Los Angeles seem like a minefield of unturned stones. He was a geographer, exploring the city by sites, teaching and learning through location—a process we believed in too. And the lessons he pulled from places were physical, forensic, and noir. Our paths crossed at local unmarked landmarks like the San Francisquito Dam ruins and at epic American places, like Utah’s Skull Valley. He reached out and opened gates, metaphorically, and in fact supported us in ways we still don’t know about. His insights, energy, compassion, and generosity were surprising, compelling, and motivating. Now gone, he leaves much disturbed and still resettling in his wake.

Margaret Crawford, director of urban design, professor of architecture and urban design, UC Berkeley

From 1988 to 1997, Mike Davis was an integral part of SCI-Arc. He taught his evolving interests and obsessions in a series of courses that combined a vast knowledge of Southern California with serious political analysis. He opened students’ eyes to issues far beyond architecture, ranging from the Los Angeles River to California’s prison system, from environmental and infrastructural history to socialist utopias and literary dystopias. His books from this period, City of Quartz and the Ecology of Fear, track almost exactly with his seminar topics. His critical interpretations were often apocalyptic, but his energy and passion were infectious.

Mike’s field trips were legendary. He took students all over the city, visiting downtown Los Angeles at night, the Oakwood gang neighborhood in Venice, the port of Long Beach, and beyond, investigating Otay Mesa border maquiladoras and Las Vegas’s workplace conditions. Mike also brought the city into the school, with prisoners, wardens, and former gang members speaking in his classes. His influence was deep, impacting the way both students and teachers understood the world, even leading some to completely reset their careers.

25 years later, we still remember your brilliance, your warmth, and your friendship. RIP Mike.

Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman; professors, University of California, San Diego; principals, Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman

Years ago, we worked with Mike and Alessandra to adapt their San Diego mid-city garage into a mixed-use writing studio, to challenge the exclusionary land-use policies of his San Diego neighborhood. This gesture manifested physically many conversations we had over the years about the creative reinvention of the American city through strategies of adaptation and retrofit. Our project together was a humble way to spatialize Mike’s thoughts in Magical Urbanism. Across many visits over pizza and Guinness, we discussed that Tijuana’s non-conforming uses could cross the border to transform the selfish, oil hungry urbanizations of San Diego’s homogenous sprawl into more complex socio-economic environments, organized around solidarity, resilience and public intelligence. Mike remains the most important pessimistic optimist we know, inspiring us always to begin our work by exposing controversy and ending with generative action. For many, his optimism was hard to detect within his relentless, damning social and urban critique. But for us, he was a carrier of hope, a polyglot always seeing potential at the margins of things, thinking the city from its periphery, linking humor, eccentricity and the politics of everyday life, while advancing the idiosyncratic cultural productivity of the marginalized to spatialize social justice. Mike will always be our cultural coyote, meandering the edges to help us cross all borders, with his amazing, grounded, subversive generosity.

Dana Cuff, director of cityLAB and professor of architecture and urban design, UCLA

I last saw Mike Davis in 2016 when I interviewed him at his house in San Diego for an article in Boom. I wanted to talk to him again because for years I had assigned his Bonaventure essay or parts of the L.A. books to my UCLA architecture students, and unlike the work of Ed Soja or David Harvey, they got a lot of traction from Mike’s writing. Upon reflection, that is surely because Mike Davis got traction from architecture and urban form. Space was not a theoretical concept for him; it was the material setting from which he constructed his political-economic reading of the city with all its inequities, and buildings were lead characters in that drama. After calling Frank Gehry’s Goldwyn Library “the most menacing library ever built,” he was summoned by Gehry to take a look at drawings for the serpentine garden which Davis acknowledged was an improbably democratic public space surrounding the “elitist [Disney] Concert Hall.” The message from Mike Davis that day in 2016 still resonates with hope and a mandate: that the best architects were radicals deep down and that sharp criticism could provoke an architect to fight “the good fight.”

Marianela D’Aprile, writer and deputy editor of the New York Review of Architecture

I read Planet of Slums at some point in my early twenties, in architecture school, grossed out by the way architects fetishized how poor people lived. They happily looked past severe structural inadequacies and lauded the workarounds that poverty made necessary. Mike called it out for what it was: a way to get out of having to solve problems at scale, while people, especially women and children, bore their burden. I was so relieved to finally have language to put to my disgust.

After years of reading his work, I reencountered Mike through the Democratic Socialists of America, where he was just another comrade happy to share his wisdom with thousands of people who wanted to engage in the kinds of class struggles he’d been writing about for decades. He was always supremely, genuinely kind, and he made everyone feel like they mattered, no doubt because he thought they did. He knew that moving a whole class toward struggle at its core meant moving individuals. What to say about Mike other than this: He just got it.

Joe Day, design and history/theory faculty, SCI-Arc

Mike Davis loved a knock-out opener. A few days after he died, my friend Arden Yang sent me a recording of his six-year-old son reading the first lines of Davis’s Buda’s Wagon, which begins: “The car bomb is the poor man’s Air Force…”

Relationships with Mike often began as his books did, with risky, often subterranean drama—a midnight drive in the L.A. River (his go-to first date test drive in the 90s) or a long spelunk down abandoned streetcar tunnels to a point directly beneath the Westin Bonaventure. Standing 50 feet below the many-turreted hotel, Mike would explain to students shivering in the glow of pocket lighters how a forgotten, more generous pre-history undergirded Frederic Jameson’s postmodern totem. For a seminar I taught with Mike at SCI-Arc a couple years later, as he was finishing Ecology of Fear, we visited two dozen prisons. By then I knew to look—and listen—for archeology as much as architecture, for sublimated pasts and forgone futures, but above all for the struggles and perspectives of those living inescapably in the present.

Keen observation, righteous fury, and rapier wit always propelled Davis’s writing and conversation, but he was sustained by a more profound adoration of those he loved (a vast denomination) and a manifold, protective wonder at the planet we share. His final dispatch unpacked the recent L.A. City Council debacle as only he could and ended with a gleeful, spiked coda: “Somos nosotros Oaxacan!” But the last private notes between us, exchanged a few weeks earlier with pictures of our children, ended with an optimism so bright that it stung: “What lucky old dogs we are, don’t you think?”

One of Mike’s favorite opening gambits, the one William Gibson coined for Neuromancer (1984), feels apt again, contemplating a future with no more of Davis’s brilliant grenades: “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.”

We will have to electrify our own gray skies now.

Nick Estes, Indigenous organizer, journalist, historian, and author of Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance

The power of Mike Davis’s “Prisoners of the American Dream” is that it shows how the US ruling class bought off parts of the working class with nationalism and racism thwarting the formation of a mass working class party. The failure of the book is that it is not read enough. RIP

— Nick Estes (@nickwestes) October 26, 2022

Anthony Fontenot, professor, Woodbury University School of Architecture

Reading City of Quartz changed everything. In it two radically different worlds were brought together, each of which I had known only separately. When the book was published, I was living in Alphabet City in the Lower East Side of Manhattan where a considerable number of my neighbors were squatters and anarchists. Marxist literature was common among the books we read and discussed. In a separate world I had been schooled in architecture and design, which had nothing to do with Marxism—or so we thought. In City of Quartz these two worlds collided. It was exhilarating to read.

While critics in architecture were exploring deconstructivism and its exalted “shattering of form,” Mike was discussing the “deconstructed Pop architecture” of “Frank Gehry as Dirty Harry.” Few critics had studied contemporary architecture in its urban context and discussed it as “barricades of exclusion” as Mike did. If contemporary urban theory had been “strangely silent about the militarization of city life” and the “destruction of public space,” following City of Quartz, we witnessed the rise of a new critique in architecture, most patently in Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space (1992) along with a list of other books that followed.

Published by Verso in 2014, Michel Sorkin, Carol McMichael Reese, and I edited New Orleans Under Reconstruction: The Crisis of Planning, and Mike graciously agreed to write the foreword, which he titled “Sittin’ on the Porch with a Shotgun.” In it he delivered a devastating blow aimed at the misguided reconstruction practices of the powerful real estate establishment of New Orleans, particularly Pres Kabacoff, who he described as a “developer-gentrifier and local patron of the New Urbanism.” In little more than six pages, Mike’s “Gentrifying Disaster” manifesto was enough of a menace to incite Kabacoff to threaten Verso with a lawsuit unless they immediately recall the book, which they did. The online version, the only edition now available, features an altered essay. Always tactical and precise, Mike used words in the way some might use car bombs.

The world of architecture, it seems, is still struggling to grasp the vision of Mike Davis. His openness, generosity, and profound commitment to working class people was unmistakable. To inspire one to fight for justice for all was at the heart of his endeavors. To miss this point is to lose sight of the fundamental message of his work. He believed that the path forward, beyond our bleak present, was to develop a greater capacity to care for one another. And finally, he understood that building a new kind of city based on progressive politics required us to “make design relevant to environmental and social justice issues” which, he insisted, “needs to be done in a greater urgency than ever before.”

A longer remembrance by Fontenot will appear in the January/February 2023 issue of The Architect’s Newspaper.

John Kaliski, president and managing principal, John Kaliski Architects

Mike Davis was one of the first people I met when I moved to Los Angeles from Houston in 1985. Diane Ghirardo, an academic colleague in Texas, introduced him to me through a reading group. I recall that our group stopped convening when we tackled Heidegger. He certainly was not interested in phenomenology. But he did want to know about architecture and the city, how practices and buildings were formulated, systems of patronage, and the deep histories and inequities of place.

When I was appointed principal architect of Los Angeles’ redevelopment agency in 1988, one of the first congratulatory calls I got was from Mike. Now, he told me, I could be his mole within this urban renewal machine. In 1989 he phoned again. He had been banned from the Agency’s archives. He was pursuing the story of the condemnation and clearance of L.A.’s Bunker Hill. Could I help him find the files?

I soon found out that I did not have access to the files. Instead, I introduced him to the one planner still standing who had worked from the start on the redevelopment of Bunker Hill. In 1992, two years after the publication of City of Quartz, that planner showed me the files. They were stashed in a bottom drawer in his office. Aha, I thought, I am the mole who introduced him to the mole that allowed Mike to better tell the never-to-completely-heal story of this urban erasure.

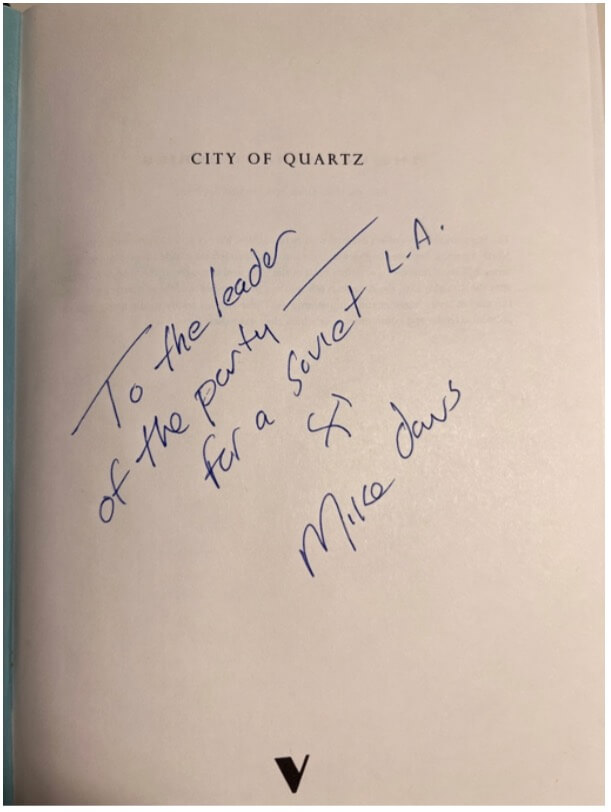

“To the leader of the party—for a Soviet L.A”, Mike wrote on the cover page of my copy of City of Quartz. I have always thought that this was a wry, unswerving, and very Mike Davis way of saying thank you for leading him to some of his source material. His special voice and commitment to urban justice through the study of place will not be forgotten.

Geoff Manaugh, writer and author of A Burglar’s Guide to the City

What drew me to Mike Davis’s work was its breadth. From meteorite impacts in ancient Siberia to riots in Los Angeles, from bird flu on industrial poultry farms to urban combat manuals, Mike went where his interests took him, without apologies. He was also refreshingly generous, opening doors for the uninvited while drawing attention to stories his colleagues might otherwise have missed. Mike recognized the fundamental role that space plays in any pursuit of social justice, highlighting urban and architectural design as a political fight. RIP to a writer who inspired many.

Thom Mayne, founding partner, Morphosis

In City of Quartz, Mike Davis brought to the surface that my city could both celebrate architecture and empower it for political, racial subjugation. At a most critical time, he established an ethical position within our profession, was fearless in his critiques, and, although extremely tough and immensely steadfast, reconnected us with the world in which we practice—pushing us toward a more potent, critical engagement with it.

Kevin McMahon, library manager, SCI-Arc

The Mike Davis I have been remembering was a fan of Lady from Shanghai and Starship Troopers. The collector of valueless currency issued by defunct revolutionary regimes. The acute—if hard-of-hearing—listener (“Are you talking about pornography or geology?”)

The lifeguard whose book projects needing my urgent assistance were really about the urgent assistance I needed to survive the AIDS catastrophe of the ‘90s. They were also a pretext for unforgettable lunches and dinners, e.g. the meal with Mike and Alessandra where his conversation consisted entirely of news stories about human parasites.

At the height of his celebrity over City of Quartz, Mike decided what I needed was a boyfriend and that he would fix me up. I was taken to a lot of parties where I met a lot of interesting and totally inappropriate people (straight, leaving town). I reminded him of it this summer, and we laughed. Laughing about that era is an accomplishment.

When I complimented him on how he and Jon Wiener crammed Set the Night on Fire with A+ anecdotes (the connection between Barefoot in the Park and Wattstax, for example), he responded, “You should see all the stuff we had to leave out.” Indeed.

Daniel Bertrand Monk, Cooley Chair in Peace and Conflict Studies and professor of geography, Colgate University

Most American urbanists are aware of the fact that Herbert Gans penned Levittowners (1967) after spending two years living amongst the new denizens of America’s postwar suburbs. Almost no one knows that Mike Davis unwittingly participated in a similar ethnography 30 years later when—around the turn of the millennium—he lived for a similar length of time on Long Island. Indeed, a fateful event there may have been the motivating experience for our Evil Paradises volume, which we originally conceived of as a book to be called Dangerous Runs. Then, five miles into a run through Hauppauge, he and I were passed by a Ford trick truck sporting a Confederate flag decal on its rear window. Mike suddenly sprinted ahead of me and caught up to this lift-kit mammoth as it parked on the side of the road. Davis yanked open the truck’s door and yelled at the top of his lungs: “Come on out and fight me, you racist motherfucker! Come on! I’ll fight you right here.” The muscular young man inside panicked, pulled the door shut, locked it, and cowered within. Not only did this really happen, but it is also an allegory of everything Mike wanted to teach me by doing what he did on that day.

Shane Reiner-Roth, lecturer, University of Southern California

Growing up in Los Angeles, I had long resisted reading negative criticism of the city, knowing full well that it was one of the great punching bags of the world.

I avoided, in particular, the depictions offered by Mike Davis, a writer who had also grown up in the greater Los Angeles region yet spent much of his career committing to paper the ugliest words he could find about this place he knew so intimately through activism and blue-collar work.

I learned quickly, however, that he did not critique this place out of spite for the people who call it home, but rather a love for them. Every perspective he offered of Los Angeles was positioned as the people’s perspective, writing not in the tradition of Reyner Banham—an armchair intellectual if the city ever had one—but Carey McWilliams, a mid-century investigative journalist-turned-historian who also saw the city as an ongoing battle between oligarchs and the working class that resisted them through courageous acts of unprecedented scale.

Los Angeles may never have a sharper critic than Mike Davis, if only because he chose not to look at the city, but through it.

Michael Rotondi, founder, RoTo Architects

Mike Davis was an optimist and a creative thinker and a man of compassion, not “a prophet of doom,” as some have written. I believe this to be so. He cared too much about others and imagined the world he thought all of us should live in, but it had to be constructed. The world as-is was not always kind or decent, and it was a world of unrest and disruption, at the scale many of us existed having but not all, not for those with power.

Mike Davis had a profound awareness and broad knowledge of the sources of disrupting power structures and provided, through his writing and public lived experiences, ways to surf the disruption and to enact maximum resistance.

When I asked him to teach at SCI-Arc, he told me he did not stay in one place very long. I asked, “What might prolong your stay here? What are you most interested in teaching?” He replied, “I am interested in power, its sources, and how it moves and influences our lives.” He was an exceptional urban theorist and historian, who lived the life he expected of others. He was among friends who needed their architectural minds deepened and expanded in unexpected ways, by someone who had an unconditional relationship with the immediate world he was currently inhabiting. SCI-Arc was his Affinity Space for a while. SCI-Arc brought people together and kept them together,

Someone like Mike Davis helped us understand what it was that gave meaning to our lives.

Matthew Soules, associate professor, School of Architecture + Landscape Architecture, University of British Columbia, and author of Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century

Buildings have come to occupy such a central position in today’s real estate–driven form of capitalism that it is hard not to describe much of what architects do as packaging financial assets that happen to be spatial. Any hope for moving beyond this dispiriting nadir and all its injustice requires us to see clearly the relationship between a myriad of ostensibly immaterial forces and their socio-spatial materializations. From the fortress of Los Angeles to the slums of Manila, Mike Davis was one of the very few people to effectively help us navigate this morass—and he did so with brilliance and an infectious outrage. His work is indispensable for those who seek a beautiful and just architecture for tomorrow.

Douglas Spencer, Pickard Chilton Professor of Architecture, Iowa State University, and author of Critique of Architecture: Essays on Theory, Autonomy, and Political Economy

Mike Davis foresaw the future of the post-liberal city better than anyone. First published in 1990, his still-essential City of Quartz surveyed Los Angeles as the site from which to excavate this future, registering the emergence of new regimes of security and surveillance, the evisceration of public space, and the deepening fractures of class and race. Davis also eyed the role architecture would be called upon to perform in this new order better than anyone else, calling out Frank Gehry’s “drunken” architecture, built “at the expense of social justice and affordable housing.” L.A. was, indeed, just the beginning.

Samuel Stein, geographer, urban planner, analyst, and author of Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State

It’s no exaggeration to say that Mike Davis was one of the great revolutionary thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries. While he was pretty much universally admired on the left, the main knock on him from my quarters of urban planning and geography was that he had a tendency toward the apocalyptic, particularly in his urban writings. But these days it’s hard to fault him for his doomerism. (Things feel pretty fucking doomy, do they not?) Davis lived by Trotsky’s admonition “to face reality squarely; not to seek the line of least resistance; to call things by their right names; to speak the truth to the masses, no matter how bitter it may be; not to fear obstacles; to be true in little things as in big ones; to base one’s program on the logic of the class struggle; to be bold when the hour for action arrives.” Mike Davis was not a pessimist for pessimism’s sake, predicting pain for the fun of it. He was being honest about the state of the world and the trajectory it was moving along so that we could act collectively to push it in another direction entirely.

Monique Verdin, filmmaker

Mike Davis changed my life and perspective, but I know I am no special case. I met him in a Baton Rouge cop’s backyard. I’d been evacuated for weeks and was retreating from Louisiana’s coast, yet again, from Rita, Hurricane Katrina’s little sister. I could barely see his face that night, I had no idea who he was, or what Marxism is or what an urban theorist did. I definitely was not fully connecting how global climate change, rooted in colonialism and extractive practices, is personal and political on planetary and generational scales; of course, that is why Davis was there.

A few short months after our faint light introduction, he welcomed me to his home, helped organize a public speaking tour, and, with the help of his incredible partner Alessandra Moctezuma, provided pathways for the first exhibitions of my Houma Nation documentation to bear witness to realities at the end of the Mississippi River. In a season of loss, which has felt neverending since that dark night in Baton Rouge, Davis has been a shining light of true friendship. He helped me find my voice and the strength to share my ancestors stories and truths—and my own.

Mimi Zeiger, critic, editor, curator, and instigator

It didn’t matter that I never had a class with Mike Davis when I was at SCI-Arc: His presence was felt. City of Quartz was on the summer reading list; I remember reading my copy on Santa Monica Beach, my brain recalibrating all my preconceptions. Los Angeles was not as superficial—as “sunshine,” as Davis put it—as I had been indoctrinated growing up in the Bay Area. It was layered and dark like a Raymond Chandler paperback. Forget it, Jake.

The forces that shaped L.A. post-1992 uprising were to be explored and critiqued with architecture as a complicit actor: defensive, militarized, surveilled. After reading Davis, it’s impossible not to look for the all-seeing security cameras in every public space. His books have caught flack for being hyperbolic and making sweeping generalizations, which is probably what made them such cinematic page turners. Looking back now, I see that his work seeped into my subconscious, swirled around with the words of other now-passed writers Dave Hickey, John Chase, Joan Didion, and Eve Babitz, and the resulting brew seeped into my criticism. For this, I’m grateful.