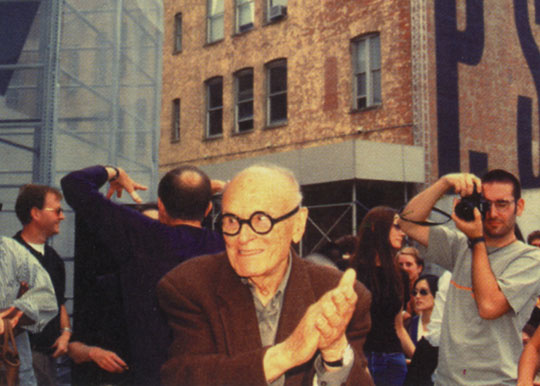

Less than a month after the $450 million expansion of MoMA, hints began circulating of the potential cancellation of MoMA PS1‘s Young Architecture Program (YAP). Begun in 1999 as the first collaboration between the merged institutions, Philip Johnson celebrated his birthday party that summer with a DJ booth commemorating the disco era, spinning Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” as the program’s initial gesture. For the next 20 years, the jury asked deans, critics, and editors to nominate 30 young firms to compete, selecting a shortlist of five to develop concepts for the annual outdoor pavilion in the Queens-based PS1’s courtyard.

“The two most open departments to collaboration from day one of the announcement were film and architecture,” said PS1 founder Alanna Heiss. “We had a gigantic space that had been used for large-scale installations of sculpture and big outdoor performance programs. We’d done a summer before of a kind of trial Warm Up, which had been more successful than, shall we say, we wanted it to be; ie., we had crowds and crowds of people that we had to devise systems to control for safety. But to merge architecture with the beginning of Warm Up was just a dream.”

MoMA’s chief architecture curator at the time was Terence Riley, who conceived of the initial framework. “An opportunity presented itself in that a couple proposed to MoMA in a meeting with Glenn Lowry [the museum’s director] and myself a prize for young architects in honor of the husband’s father,” said Riley. “He was focused on young architects, and he was thinking that it would be a prize. I was wary and am now about museums giving out prizes. It was really at the spur of the moment that we flipped the conversation to this Young Architects Program. Probably more than any kind of a medal, getting the opportunity for a young architect to actually build something in New York City—which is a freestanding element rather than an interior—I thought this would be super exciting for the museum and for the cadre of young architects of the period.”

Marcel Breuer had built a temporary house in MoMA’s garden in the 1950s, and the Serpentine Pavilion in London also began in 2000 with a much larger budget. The Venice Architecture Biennale’s pavilions bear some resemblance, too. During his time as MoMA’s chief architecture curator, Barry Bergdoll instigated the impressive Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling in 2008, building housing models in MoMA-owned adjacent lots, which pushed the temporary building program in another productive direction. But YAP was the first temporary pavilion program of its kind in the world.

“The first winner was SHoP, and it set a very high standard,” Riley said. “It immediately became super competitive, and what I think is amazing, people put so much effort into it, many of the installations stand out as being a turning point in a lot of careers for some amazing architects. You can make a list of them. It’s pretty incredible.”

YAP became an influential model around the world, with MoMA organizing partner pavilions at the National Museum of XXI Century Arts (MAXXI) in Rome, with CONSTRUCTO in Santiago, Chile, at Istanbul Modern, and at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul.

“The fact that it has a use was critical in the sense that it wasn’t just architects scribbling and coming up with seductive forms, although they often did, but they did often have a focus and guidelines,” Riley said of YAP. “That gave it some rigor and also some humor. This was for a DJ event. It was about fun; it was about enjoyment. It had it’s own character, which was really great.”

AN asked past YAP winners and curators to comment on its value to their careers, to young architects, and to the field, and to suggest possible future directions for the program.

AN: How would you evaluate the program as a platform for you or other young architects to develop their ideas and gain recognition?

Florian Idenburg, SO-IL

For SO-IL, our installation, Pole Dance, was career-defining. We cannot recognize enough the importance that the program has had on a generation of architects. This potential is something MoMA should not underestimate and should try to maintain as it finds its new form. After two decades, any temporary event starts to lose its potential. I am excited to see what comes next.

Eric Bunge, nARCHITECTS

The program has undoubtedly been a launchpad for architecture firms, including ours, but its more important impact has been as a petri dish for ideas.

Pedro Gadanho, former MoMA curator of architecture and design

In a context in which debt-ridden young architects probably have to enter corporate offices just to survive, YAP provided one of the few design opportunities in the U.S. in which a smaller scale, more experimental studio could try out architectural ideas outside the market. And with MoMA’s notoriety [renown] behind it, winning it surely provided a boost in visibility at [an] international level. In this sense, after such a history has been made, scrapping it sounds profoundly unfortunate for the architectural field in the States, as well as for MoMA’s role within it.

Gregg Pasquarelli, SHoP founding principal

This program was an incredibly important platform for SHoP and other young firms. Dunescape [in inaugural 2000] was one of the first projects that put SHoP on the map in a meaningful way, and we are very grateful to have been a part of MoMA’s incubator. It showed us the tremendous R&D value of designing and constructing exhibitions and temporary pavilions and informs the way that we work to this day. What we learned through Dunescape has proven scalable and enabled us to conceptualize a new way of working that we are hopeful will revolutionize the entire architecture and construction industry.

Jenny Sabin, Jenny Sabin Studio

Winning the 2017 MoMA and MoMA PS1 YAP competition marked a major transition point in my professional creative career. My built work up until that point had been largely experimental, indoors, and at the pavilion scale. The platform enabled me to push design research to an entirely different scale, to engage active environmental conditions, diverse publics, and to respond to and integrate unique public programs for Warm Up. I can’t underscore enough the positive role and impact YAP plays in our field and practice. It was the most rewarding and meaningful project that I have completed to date. It was an incredible honor and the international exposure was mind-boggling. YAP elevated my practice to an entirely new level with new and ongoing projects all over the world.

Tobias Armborst, Interboro Partners

For Interboro the program was important, changing the trajectory of our work. The particular response we found to the question of temporary architecture really brought forward our interest in rethinking community engagement and developing architecture not only as a product but as an open process that can involve many actors.

Pablo Castro and Jennifer Lee, OBRA

The YAP program was of course not perfect, the budget was too modest and so were the design fees—in our case our aim to adequately respond to the programmatic requirement of shade ended up being achievable only after being supplemented by a huge other fundraising effort on our part. In later years YAP had also become a franchise for MoMA, sprouting sideshows all over the world. Museums in Santiago, Istanbul, Rome, and Seoul had their own versions of YAP. Sometimes the work produced for these colonial outposts was interesting, but one can’t help but wonder if it would not have been better to focus more concentratedly in advancing the conceptual intentions of the effort instead of multiplying it without any kind of contextual adjustment all over the globe.

By 2006 when, thanks to YAP, OBRA got its chance to build Beatfuse! in the courtyards of the museum, one could already sense in the place a feeling of being under the intervention of some kind of colonial financial overlord. We were lucky enough to still enjoy the residual presence of the original “guerrilla” attitude which was alive and well in the people that ran and worked in the place: Alanna herself, a great champion of the daring and inspired; Brett Littman, the deputy director who saved our skin several times as we were trying to build Obra’s overly-ambitious proposal; Tony Guerrero, the chief installer who—as I remember—used to keep a huge cage full of birds inside his office; and Sixto Figueroa, the congenial head of the Boricua-dominated PS1 shop, the place which, that spring, all of the sudden became our second home.

How would you evaluate its success or limits as a model?

Pedro Gadanho

Its success depended entirely on the architect’s propositions, and how [over] time these could provide yet another design insight into a constricted site, namely by advancing more conceptual alternatives into low-budget construction systems, environmental inventions, and sometimes fascinating functional add-ons. Its limits were the usual ones for this type of initiative: that budgets were never as elastic as architects would love them to be.

Terence Riley, former MoMA architecture and design curator, founding partner K/R Architects

I definitely think it’s a really good thing. Architecture is so abstract now: BIM modeling and so on—I just remember someone asking me, is that a photograph or a rendering? There’s this lack of certainty, at least in the world of reproduction. The young architects who got involved in these projects, I am certain it’s the first time they were on a job site in such an extended manner and felt the building up close in terms of materials and how things went together.

In the beginning, it also addressed the local issue: the lack of younger people to build a building in New York City. It was amazing how much it expanded because of this hyper-competitiveness that seized that whole generation.

Where should it go in the future, if it continues, or has the temporary pavilion framework been exhausted, as some critics have suggested? Or what should they do instead?

Florian Idenburg

Yes, a rethink is very timely. The wide range of issues that at this moment is leading to rage and despair on the streets of the world are real signals that there is an urgent need for real action and real change. The institutions that we brought into the world to “educate” the people—the museums, libraries, and universities—will have to decide. Either remain on the sidelines and continue to offer repose and shelter from the pressures of this much-needed realignment or become active participants. One can imagine the MoMA partnering with city agencies or nonprofits and developing a program in which they sponsor design fees for young architects to work on actual projects that have lasting benefits for people. One can imagine projects that take multiple years and are developed collectively, possibly using PS1 as a space for debate, work, and communication.

Eric Bunge

It should definitely continue, not only to maintain MoMA’s crucial role in catalyzing architectural ideas, but to continue engaging wider publics.

The framework that is important to maintain is the constant renewal of the courtyard, not necessarily one that produces a pavilion. That’s just a problem definition.

I think MoMA should find a way to bring back some of the simplicity of the early years, and address the increasingly [difficult] challenges faced by young architects:

- Cover or reduce the insurance requirements. There were none when we built Canopy; we therefore made it as safe as possible.

- Start the process much sooner, to allow for more time to design and build.

- Encourage the architects to design ephemeral environments with the thousands of users in mind, as opposed to (only) creating objects.

Pedro Gadanho

The inventiveness with which every participant’s solution showed new possibilities for that site showed that the model was the opposite of exhausted…

Gregg Pasquarelli

We’re big fans of the temporary nature of the pavilion framework. There’s something exciting and liberating about a project that exists only for a moment in time. The best pavilions have come from the freedom and invention of this approach.

Jenny Sabin

In taking this hiatus to reevaluate YAP, MoMA is in a unique position to reframe the value of architecture to the broader public and within our niche architecture communities. I don’t think the temporary pavilion framework will ever be exhausted. That’s like saying architecture has been exhausted. I think the platform needs to be evaluated, and refreshed with eyes on the pressing issues of our time. Important areas that should be examined and discussed include labor, budget, waste and sustainable materials, liability, context, and program—all of which are integral architectural constraints and parameters.

Tobias Armborst

I went to a discussion of former YAP winners at MoMA recently, and some of those questions were raised there: Is the pavilion still relevant given that there are so many competitions for temporary pavilions now? Is this still the right site? I came away from it thinking that in spite of the changing context, YAP still kind of works as a stage for young architects to present ideas. It’s great to see all these different responses to the site and the temporary nature of the project. However, one aspect in which the program could use an update is perhaps less a change in venue, program, or duration, but in rethinking the compensation. It seems like the program is still based on an outdated idea of self-exploitation on the part of architects, and the expectation of a lot of free labor on the part of students, volunteers, etc. Thinking about new ways of providing fair compensation for design labor (at least the labor of “volunteers”) I think would be [a] very timely update. I don’t mean to just ask for more money, but I think there could be a greater acknowledgment of how architecture is actually made, and by whom, in a rethinking of the compensation model.

Pablo Castro and Jennifer Lee

Seeing the YAP program suspended is indeed not only sad but also a little bit ominous. In a way, we fear YAP’s demise corresponds all too well with the less-than-absolutely-thrilling zeitgeist under which we all live these days in New York City. It makes it only too obvious that time has run out for art (and architecture) as a form of insidious and idealistic cultural guerrilla-warfare. We fancy that was the spirit under which PS1 was originally created by Alanna Heiss in 1971.

Should they commission a more durable conversion of the courtyard?

Eric Bunge

A durable conversion would be a huge missed opportunity. Better a series of interesting potential small mistakes than a permanent potential big one. The emptiness and randomness of that courtyard is the cool counterpoint to MoMA’s sculpture garden. If only every other cultural institution had such a powerful void and the bravery to periodically fill it and empty it. So much of its value is its perpetual renewal.

Pedro Gadanho

I don’t think a “more durable conversion” substitutes the curatorial trajectory that YAP represented. That would be just another commission, which any museum does regularly to update spaces [to fill] to their needs.

Gregg Pasquarelli

I’m not sure it’s our place to comment on what form the program should take, but we look forward to seeing what they come up with next!

Terence Riley

A lot of programs in museums are dependent on one donor who is willing to subsidize it in perpetuity. People wanted to be involved with this because it was frankly a success, and having SHoP lead with such a strong project definitely set a fairly high bar. When I say it’s still useful, that doesn’t mean in an abstract sense—where that happens isn’t really relevant. Could it have gotten stale in Long Island City at PS1? Certainly at this point I would find it hard to think that there was a huge amount of excitement, at least the kind of excitement that there was in the first decade, shall we say. It wasn’t just among the young architects, it was also in the media it was covered nationally and internationally; and so on one hand, it’s still relevant, on the other hand, a pause doesn’t sound like a terrible thing. Things could be done in different ways. I did start the program, but I don’t feel that the museum’s doing something unethical or whatever. Maybe it’s time for a pause.

Jenny Sabin

I think this requires discussion with previous YAP winners, nominators, students, the architecture community, and Warm Up partygoers, and that’s exactly what MoMA is doing. I’m excited to see what happens next.

Pablo Castro and Jennifer Lee

The successive curators of architecture at MoMA, Terence Riley, Barry Bergdoll, Andres Lepik, Pedro Gadagno, and Martino Stierli all seemed to have done their best to steer YAP toward a position of meaningful significance every year by proposing enlightened programmatic propositions:

The project aims to explore and improve upon the quality of public space by implementing the elements of shade, water, seating, bars, and sustainability at this site…

The commission is to design and realize a project for summer relaxation and interaction—offering the sort of space often denied to urbanites…

After over a decade of successful YAP projects, we now focus the competition to encourage designs based on themes of sustainability, recycling, and reuse…

This year, we are keen to consider new materials and materiality as a component of the portfolio (and, ultimately, the final design schemes)…

We seek designs that are environmentally sensitive, provide elements of shade, water, and seating while also having [the] potential for fun!

All these goals were of course very worthy and desirable, but also hardly in keeping with the revolutionary disruptive objectives with which MoMA first came into prominence in the early 20th century. To be fair, by the turn of the century perhaps the boat had also already sailed on that. Nonetheless, we daydreamed that YAP could have evolved at some point to become the vehicle for putting forward a more considered project for the future of architecture and the city using its public platform to publicize and disseminate a more progressive vision of the future of the built environment. Perhaps something other than urbanism via real estate speculation and architecture via marketing spectacle? Who knows?

Notwithstanding these shortcomings, YAP was a valuable program that allowed a rare channel of expression for architects making their first foray into the discipline. As one of the beneficiaries of such initiative, we regret its discontinuation and hope for its return.