A House-Bath Appearing Twice, Crudely

SCI-Arc Gallery

Los Angeles, CA

October 20, 2023–January 21, 2024

Iterations are procedures of repetition that test, analyze and refine ideas. They’re examples of best practices in any design studio. Successful projects are more likely products of successive approximations than spontaneous instantiations. That’s what we were taught in school anyway, and it’s what we tell our students. Copying is much less interesting than testing to failure, and that’s where much of the profession aspires to fall.

To be sure, making architecture operates within a complex framework of constraints, ranging from budgets and maintenance to codes and institutional standards. So, where are the optimal working environments in which iterating can thrive? In many offices, these explorations rely on drawings and models (especially models) that fall under the category of “study.”

There are architects (Herzog & de Meuron immediately comes to mind) that show lots of study models in exhibitions and publications, but it’s safe to say that they are exceptions to the rule. As the word implies, studies are not “finished” and thus more suited for internal deliberation than for public consumption. Architects don’t usually like to air their dirty laundry.

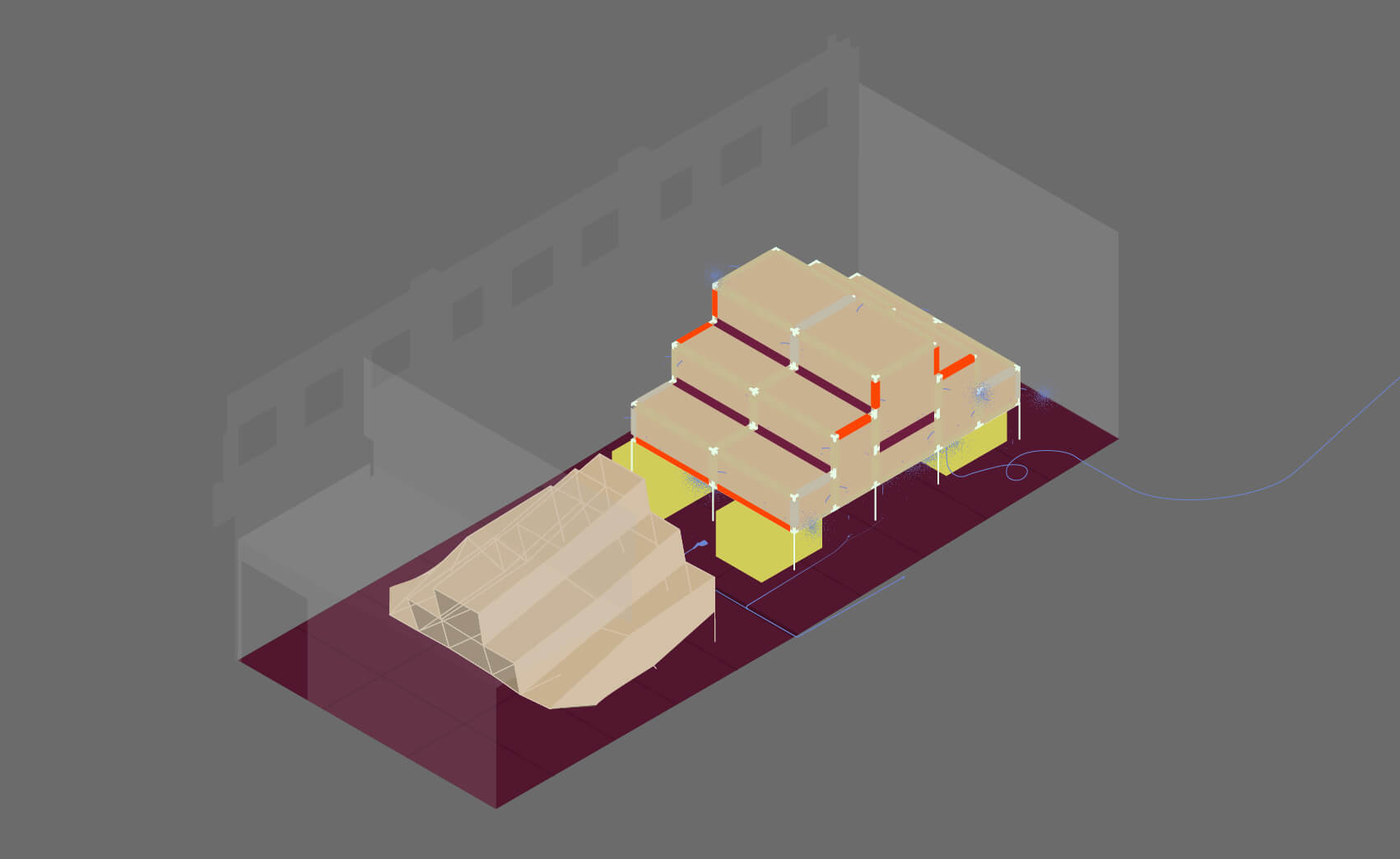

Repetition not replication is where David Eskenazi’s latest work, A House-Bath Appearing Twice, Crudely, resides. Staged recently at the SCI-Arc gallery, the installation consisted of two models that hovered somewhere between study and finished, or better yet both/and. The latest in a series of tectonic and typological iterations, House-Bath continued his earlier explorations: Slump Model (2019), shown at the Wedge Gallery at Woodbury, and Inhale, Exhale, Sag, Flex (2020), which was recognized with an AN Best of Design award the following year.

Eskenazi’s work comes out of an institutional upbringing that is firmly planted in the digital, but his curiosity extends to analog production. In the case of House-Bath, one structure was made of paper and tape, while another was a more typical frame-and-panel assembly, albeit with industrial grade nylon, pond liners, pipe fittings and fiberglass rods, and more paper. Together, they appeared and behaved more fraternal than identical: While they originated from a shared research project and had similar formal characteristics, but they had distinct construction logics.

And if these are models in our conventional understanding of the term, what kind are they? Their relationship to scale is fuzzy, but Eskenazi makes it clear that they are not abstractions that serve as stand ins for “real” buildings. They are not representations of other things but are rather meant to be taken at face value. They too are buildings (of a sort)—unruly assemblages that are stretched, fastened, crumpled, sewn, stapled, screwed, and taped.

These material choices and fabrication methods would in other contexts be considered too fragile and provisional to be taken seriously at a 1:1 scale. Certainly, in an academic setting and presented at a crit, they could be termed “weak.” But weakness is a productive attribute in Eskenazi’s world. These are not architectures that resist the inevitability of gravity, nor are they impervious to weathering. The circulation of water in the larger model elucidates this: As the pond liners fill, the panels become heavier, and the system starts to droop and leak. Furthermore, you are invited to engage with them bodily. Touching the paper model and wandering under the scaffolding, I couldn’t help but wonder how advantageous it was to experience them at the tail end of the exhibition when their listing postures were most pronounced.

Surely this is not the proper way to make a building, and yet propriety is a useful term in this context because it reflects not just Eskenazi’s authorial sensibility regarding craft (he prefers “craft-like” to “craft”), but also his subject matter. Bathing is best done undressed and is also usually done at home—thus the hyphenation of “House-Bath.” Naked bodies make for tricky clients.

Jasmine Benyamin is an architectural historian, theorist, and lapsed practitioner. She teaches at USC and resides in Palm Springs.