Over the past three weeks, Christopher Columbus has been both drowned and decapitated, and Edward Colson, the man whose personal largesse help to build the British port city of Bristol, was chucked into a river. King Leopold II of Belgium has been both physically and verbally attacked. Winston Churchill was provided with bodyguards before being put into a protective box. Jerry Richardson, the former owner of the Carolina Panthers, was spirited away by a truck before anything could happen to him. In cities ranging from Nashville to College Station to Portsmouth, Virginia, long-dead figureheads of the Confederate States of America have been introduced, some for the first time, to the mid-century invention known as spray paint.

In addition to acts of vandalism, the now-global protest movement spurred by the killing of Black Minneapolis resident George Floyd at the hands of that city’s police department has also spurred the coordinated mass removal of Jim Crow-era Confederate monuments—once numbering north of 700, a figure that’s swiftly falling—across the United States. Meanwhile, both at home and abroad, statues of historic figures associated with genocide, the trading of enslaved people, murder, and acts of cruelty inflicted against Indigenous people and people of color have been trashed and toppled, if not preemptively dismantled and cleared away first (in the case of Richardson, his statue was removed due to accusations of serious workplace misconduct).

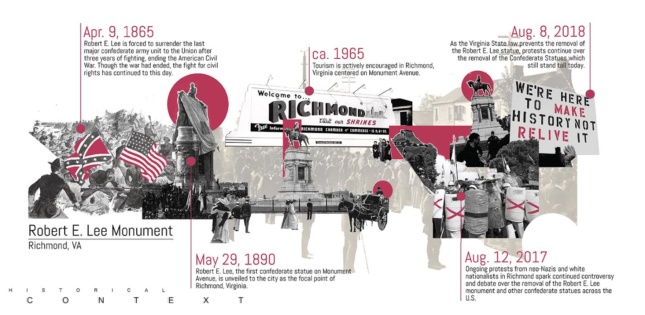

Prior to the recent unprecedented civil rights demonstrations, numerous Confederate statues were detached from their plinths in 2015 following a mass shooting perpetrated by a white supremacist in Charleston, South Carolina, at one of the oldest Black churches in the country. In the aftermath of Unite the Right, a deadly neo-Nazi and white supremacist rally held in Charlottesville, Virginia, in April 2017, more Confederate monuments were removed from parks and other public places. (The rally itself was held in protest of plans to remove a statue of Confederate commander Robert E. Lee.) Various cities and states across the country have been putting Confederate monuments into retirement ever since, with Texas leading the pack, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. The desire by citizens to put these monuments out to pasture often stretches far back, with removal efforts prompting heated, years-long debates. Meanwhile, Americans remain largely split on the issue, with a little more than half of the people polled in 2017 believing that these public landmarks should be kept in place (those numbers have since slightly shifted).

This past academic year, students from the School of Architecture and the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Oklahoma State University participated in a cross-department design studio that explored the idea of preserving Confederate statues while reframing them through the power of reactivated public space. Confederate monuments erected during Jim Crow were largely deployed as tools of intimidation meant to menace and dominate, and the aim of the OSU project was to essentially flip the switch.

As Keith Peiffer, an assistant professor at OSU’s College of Architecture and one of the three faculty leaders of the project, explained in a statement: “I believe we can have a dialogue about how to work within this contentious context, using design to go beyond simple removal to preserve the historical monument while dramatically recontextualizing and reframing the experience of the monument to confront issues of systemic racism and white supremacy.”

Noting the “somewhat generic” void left behind by expelled monuments, Peiffer told AN: “I’m hoping that what we’re seeing now is people being awakened or becoming aware of things that they didn’t understand. And using design as a way to create that conversation around an artifact with a troubled past is a more compelling way of engaging that than simply removing it.”

Developed by Bo Zhang, assistant professor in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, and led in collaboration with Peiffer and Awilda Rodríguez Carrión, associate professor at the College of Architecture, the project took the form of a four-week studio session during the fall semester and continued during an abbreviated three-week spring session in May.

“Attacking this subject has been on Professor Zhang’s plate for a while,” Rodríguez Carrión said of the project’s timing. “It’s tricky to approach a subject like this in the studio but this year we felt it was time to open it up and start a conversation.” Carrion added that the issue of monument removal extends beyond America’s fractured, racist history and touches down on the horrors of European colonialism, the impacts of which are still being felt today. “For me, it’s a subject that hit home, too,” she said.

“We lose the opportunity to connect back to our history and also create opportunity to have dialogue in public spaces,” added Zhang of the drive behind a project that envisions painful monuments staying put. “We lose a starting point to contemplate the issues [presented by the statues].”

For the project, ten interdisciplinary teams of four students each were tasked with conceiving a design proposal and accompanying manifesto—a way for, in the words of Carrion, students to “graphically express their emotions”—for one of five Confederate monuments or monument sites selected by Zhang, each diverse in its geographic locale, form, and level of local controversy. Each site was assigned two teams. At the time of this writing, several of the monuments in question have already been removed. The sites were:

- Monument Avenue, a prominent, mall-straddling street in Richmond, Virginia, where equestrians sculptures of Robert E. Lee along with two other Confederate leaders are currently on their way out (pending legal battles) and a 1907 memorial to Confederate president Jefferson Davis was toppled by protestors earlier this month. The one statue of an African American on Monument Avenue, the late tennis great Arthur Ashe, has also been defaced.

- The Norfolk Confederate Statue Monument, a Confederate memorial in Virginia’s second largest city that was also completed in 1907 and dismantled earlier this week.

- Charlottesville’s Robert E. Lee Monument, which still remains standing in its current location after serving as the focal point of the aforementioned Unite the Right rally. (That monument and a statue of Stonewall Jackson were shrouded in black tarps for less than a year starting in August 2017.)

- The Confederate Monument in Louisville, a huge and ornate 1895 sculpture that was dismantled and moved in late 2016, for “the sake of tourism” per Zhang, to the small Kentucky city of Brandenburg following years of relocation efforts.

- The Confederate Soldiers and Sailor Monument, a 1912 granite Confederate monument in Indianapolis—one of very few in the state of Indiana—that was dismantled and removed from a city park earlier this month by the city.

The teams kicked off the design process by conducting research and analysis of each site while considering the “historical, political, and social context” of each monument. From there, the teams proposed unique interventions meant to “keep the history alive but also to critique and reframe it.” Informal and formal critiques of each proposal followed. Professors from both the School of Architecture and the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture participated in the critiques and were joined by relevant members of the OSU history department. A public presentation of the 10 monument-reframing proposals was held at the heart of OSU’s Stillwater campus, the Student Union Plaza, on September 25, 2019.

Peiffer described the initial weeklong research phase as an invaluable element of the process as it exposed many students to history that they were largely unaware of. “I know some of the students were a little more socially active and engaged, and this was near and dear to their hearts,” he said. “Others were definitely learning along the way about things they’d never heard of before.”

“We wanted to help them understand that design is not neutral, we can take a position, and that’s part of what we’re doing—we’re not just designing public space but we’re taking a position about things that really matter,” he added.

Rodríguez Carrión added that early debates about the fate of each assigned monument “ignited very interesting conversations between those making the decisions.”

Those decisions have yielded a batch of dramatic design proposals. Reframing, one of two proposals that focused on the massive Robert E. Lee equestrian sculpture on Monument Avenue in Richmond left the monument largely untouched and instead proposed a “linear spatial sequence to re-frame the viewing of the monument,” explained a project overview. “Specifically-designed platforms with interpretative signage provide places for visitors to see the monument while contextualized by the history of the Reconstruction era, Jim Crow Laws, and the Civil Rights movement.”

“Our first instinct when approaching this project was to just remove the monument or deface it but with the idea that we should consider presenting a design decision that’s unbiased and educates rather than destroys,” explained Hope Bailey, an architecture student on the Reframing team. “We literally created a gash in Monument Avenue that gives pedestrians different views of the monument, and at the end of the long walkway toward the monument we created a space for discussion and protests.”

The second Monument Avenue-based proposal, Memorial Avenue, lowers the enormous base of the Lee statue into the ground so that, in the words of student team member Braden King, visitors can engage in “healthy discourse” while directly confronting a symbol of “hundreds of years of injustice and hatred.”

“Our goal was to take the statue and suppress it,” explained King. “How do you take the focus off of him and put the focus it on the narrative?”

To achieve this, the proposal envisions a sequence of four themed stages clustered around the sunken Lee statue. “A carefully integrated sequence of experiences guides the visitors through transition/preparation, a moment of pause, a didactic exhibit giving historical context, and a park to encourage reflection and interaction,” reads the project statement. “Memorial Avenue places value on truth and honesty in the historical narrative of such a monument and transforms a divisive topic into a generator of discussion and examination of the past.”

Of course, deploying design to shift the perception of public-facing relics that symbolize a failed attempt to preserve slavery isn’t a solution that everyone will accept. Many would like to see all Confederate monuments and other hate-embodying statues—be it of a British imperialist or a South Carolina senator–removed and erased from the public space entirely. But the proposals put forth by the student teams at OSU, all of them using design to minimize the monuments and create landscapes that promote public dialogue and reflection, is an alternative that could be employed moving forward. And as Zhang pointed out, some of the proposals are “still valid even after the statues are taken away.”

“We want to be clear that we definitely agree that something needs to be done with these monuments,” said Peiffer. “They can’t be kept as is. But by offering a design and putting something out there then we can start to argue, debate, and engage these sensitive issues.”