Part two of Denis Villeneuve’s Dune megafilm will surely hold the attention of design-sensitive viewers, as what’s so captivating about the series isn’t merely the plot, but the settings. The tale is adapted from the 1965 book by Frank Herbert and follows 40 years after David Lynch’s adaptation. In Villeneuve’s version, production design and CGI engineering for these films take the designer’s task of “worldbuilding” to new heights. Their efforts result in a film whose plot is intentionally advanced by its set design.

Herbert’s original science fiction tale arrived during the golden age of the genre, when writers were translating contemporary issues to “faraway” places to allow the distance to engage in societal critique. The black-and-white, good versus evil depiction of Dune’s heroes and villains depict the Fremen on Arrakis and the Harkonnens on Giedi Prime, while the white savior Paul’s (Timothée Chalamet) House Atreides occupies a tense middle ground—perhaps a Marshall Plan–era United States?—due to equally tense ties to the galactic imperial system of feudal rule.

Villeneuve uses the power of architecture and environment to complicate morals and intentions far beyond blue and red lightsabers. Today, Western society largely resembles the Harkonnens’ crude and cruel attempts at wealth-building through resource depletion, colonization, and hierarchy. Just as future society can’t live without spice, today we feel we cannot live without the thick, black fossil fuels that power our world. But there are also relatable glimmers embedded in the world of the emperor, whose political realm unifies myriad planets and “ruling families” a la Game of Thrones. Referred to as “The Imperium,” it’s ruled by a weak Shaddam IV Corrino, played by an oddly cast Christopher Walken. The Corrino family compound was the most widely discussed architectural artifact of the series, but Carlo Scarpa’s Tomba Brion only got a few fleeting cameos as the cameras moved in and beneath its keyhole arches. While recognizable, this comfortable, human-scale architecture does not fuel the film’s exciting worldbuilding.

Dune is about landscape, earthen resources, and living lightly upon vastness. And the battle between good and evil doesn’t solely depend on honor, chivalry, and loyalty: There’s an equal amount of respect established by embracing proto-Indigenous knowledge, or what we, as 21st-century viewers, see as traditional ways of living and building. Above all, this means relinquishing the human desire for control over the natural environment.

When House Atreides members first land on Arrakis (or Dune, in the Indigenous tongue) they see no signs of habitation. The Fremen dwell lightly enough on this planet as to leave its surface undisturbed (the opposite of Giedi Prime, the film’s proxy for modern society). The Fremen build sietches—vast caves beneath the desert which provide shelter away from the sun, heat, and wind—rather than erecting forms to overcome these conditions.

The desert climate of Arrakis (shot in the United Arab Emirates) served as a splendid foil for part 1 cameos of the Atreides home planet (shot in Norway), a misty place dotted with islands surfing on a raucous sea. Now part 2 ushers in an even more striking comparison. When viewers land on the home planet of the Harkonnens, we move from a warm, earth-toned color scheme and varieties of melanin-rich peoples to the literally black-and-white realm of the series’ villains.

Villenueve’s depiction of the Harkonnens’ home planet is one of the most disturbing and surreal sequences of cinema I’ve seen recently. First, viewers hear Hans Zimmer’s ceaseless beat of the steel hammer. The score makes the entire world sound as if perched on the top of a planet-sized factory. Then, on screen, Giedi Prime is experienced through a video-cam lens inset into the techno-chic opera glasses worn by Margot Fenring (Lea Seydoux), a mystic from the Bene Gesserit cult that propels the matriarchal plotline. Everything is milky, shadowless whites and Anish Kapoor black. Faces have no peaks and valleys—let alone eyebrows—but lips are painted dark in a way that references ohaguro, the medieval Japanese beauty practice of blackening one’s teeth.

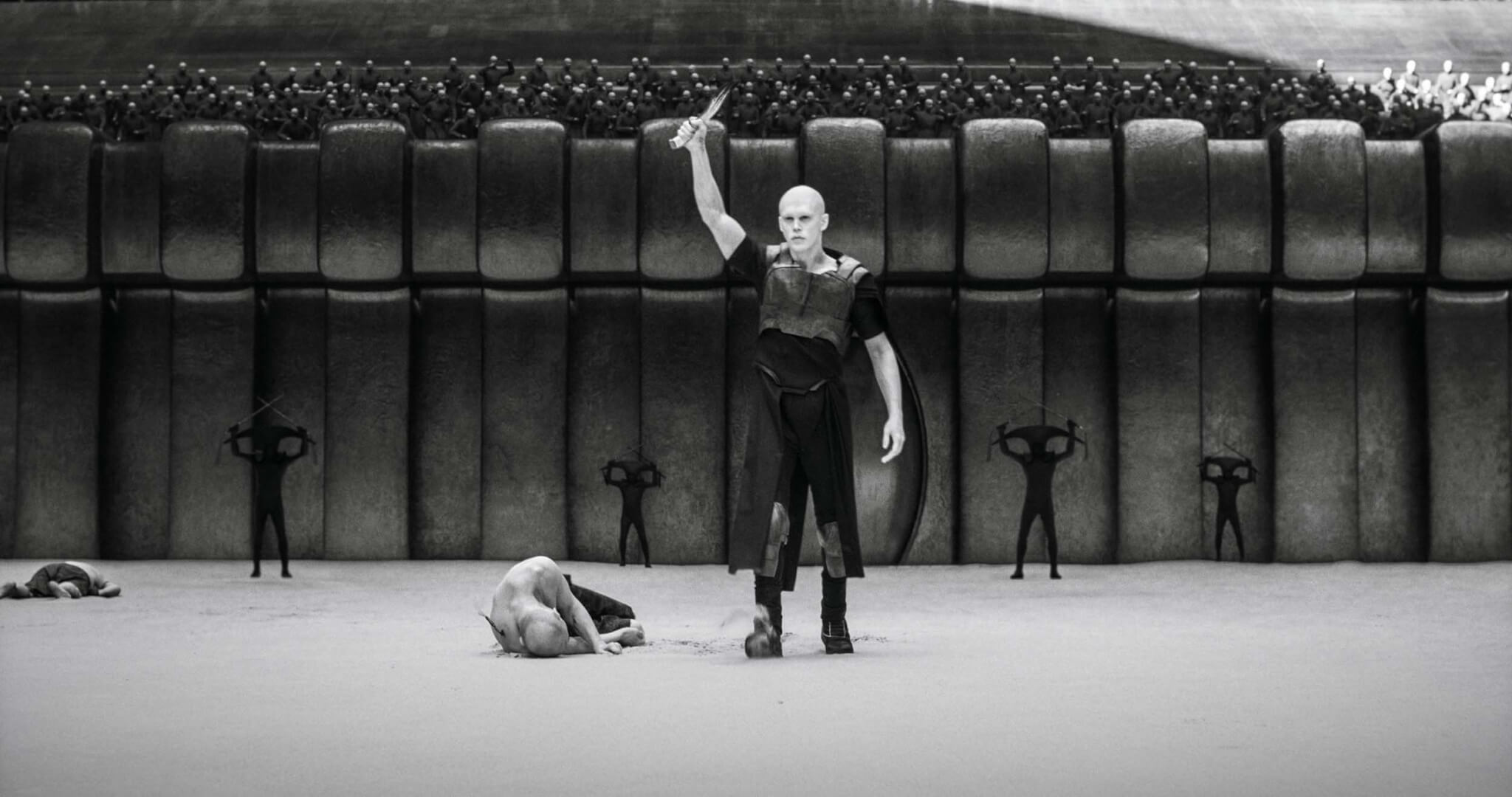

There is no “outside” in the Harkonnen world. Through Fenring’s glasses, we experience Giedi Prime in celebration: It’s Feyd-Rautha’s (Austin Butler’s) birthday, an event marked by a WWE-style staged fight in a Roman colosseum. Dune’s existing mix of cosmic futurism and ancient aesthetic gets another layer on the Harkonnen planet though. In the black-and-white procession, there are clear allusions to the early film recordings of Hitler rallies—processions flanked on either side by bleachers of white, faceless followers cheering in militant fashion. Science fiction has always commented on fascism, industrialization, and war—think Star Wars, Lord of the Rings—but this scene explicitly links the Roman colosseum with right-wing fanaticism. It all climaxes in the Bene Gesserit’s misplaced belief in Feyd-Rautha’s masculine heroics.

The city constructed by the Harkonnens on Arrakis is a pale comparison to their Giedi Prime home, but it too is organized according to an introverted plan. Everything can (and must) be sealed: There are high stone walls, and there is a hierarchy represented physically in elevation, growing from the lowest points at the city fringes to the summit of the central palace.

By contrast, the Fremen have no such delusions of grandeur and security on Arrakis. Their architecture is one of expanse, but below the sands. In Domus’s take on the film, Gabriele Niola invokes the Alhambra to describe the sietches. Vaulted ceilings with elegant details do filter light from skylights hidden somewhere in the eaves, offering the feeling of dappled stained-glass light akin to a sacred architecture. While I wish the film would have lingered more in the sietches, we still feel close to the earth in these hollowed-out caves, niches in the rock, and, of course, a sacred pool of dead water. Out in the desert, their practice of resting lightly beneath the surface extends to tent habitats—tented beneath, rather than on top of the dunes—and to fighting tactics: Fremen soldiers hide beneath the sand before attacking.

Arrakis seems an environmentally hostile place to live, but its deserts are the main scenography for Villeneuve’s part two, itself nearly three hours long. To test people or kill them, Fremen need only to “let the desert take them” (the equally terrifying prospect of the worms or the cannibalistic practice of killing your partner to harvest their water). Setting aside the battle scenes, Dune is one window into the potential future of our climate emergency. From our seats, we watch an alternate way of living on a water-scarce planet. We see marginalized communities rise up against resource extraction, and we also witness the wars and violence waged by their oppressors. (Similar resource wars are born out in sci-fi films like Mad Max: Fury Road.) Still, the Fremen thrive, and the obstacles of their home planet are harnessed in a way that showcases a nearly harmonious relationship. This is partially due to the story’s invocation of not the stereotypical cyberpunk aesthetics of sci-fi, but more radical warnings, teachings, and observations often found in the works of Ursula K. Le Guin.

The toughest lesson is that this requires letting go. Le Guin’s characters are deeply mindful of planetary lessons, the mistakes made when trying to dominate nature, and the movements and ways of all forms of life. Her short story about Dira, the man as parasitic as a tick, is just as much of a fable as Dune’s helicopter scene, as both have lessons to share.

The series’ most riveting scene occurred in part one when Paul and his mother are escaping enemies via ornithopter. The pair drives straight into the storm, following advice from a native Fremen. “That’s your best chance,” she told them, but as viewers we see it as a scenario leading to certain death. The scene sends the viewer into a full tailspin of anxiety for several minutes, seemingly in a single take. But Paul’s heroism in this sequence doesn’t stem from his mastery of the flight craft or his cunning bravery. Seeing through the storm some hidden path of least resistance: He actually gives up, shuts down the engine, and enters free fall. Paul lets the small copter be flung into the storm, and that release is what saves them.

When architects emerge from Villeneuve’s six-hour saga, what endures isn’t just the thrill of a Scarpa sighting, but rather the film’s message of living lighter upon, and more compassionately with, the earth. Such is the power of the sci-fi genre to create wholly new worlds without relying on the literary advice to “write what you know.” Dune offers a window into an alternative spatial practice that melds the best of passive, site-sensitive building tradition and technology while furnishing a ruthlessly clear vision about what happens if we keep ignoring our climate crisis.