Author’s note: This article is a draft introduction for a book-length project on the connection between landscape and building tastes and the erasure of Indigenous cultures in the upper Midwest. In Minnesota there are very few architects and landscape architects from Native cultures. As this book project progresses, I am seeking out Dakota speakers, historians, and linguists to advise and comment. This essay reflects some of their input. But more is needed. As a landscape historian, my focus in this article is to introduce a critical gap in academic and professional design discourse—both communities with few Indigenous voices.

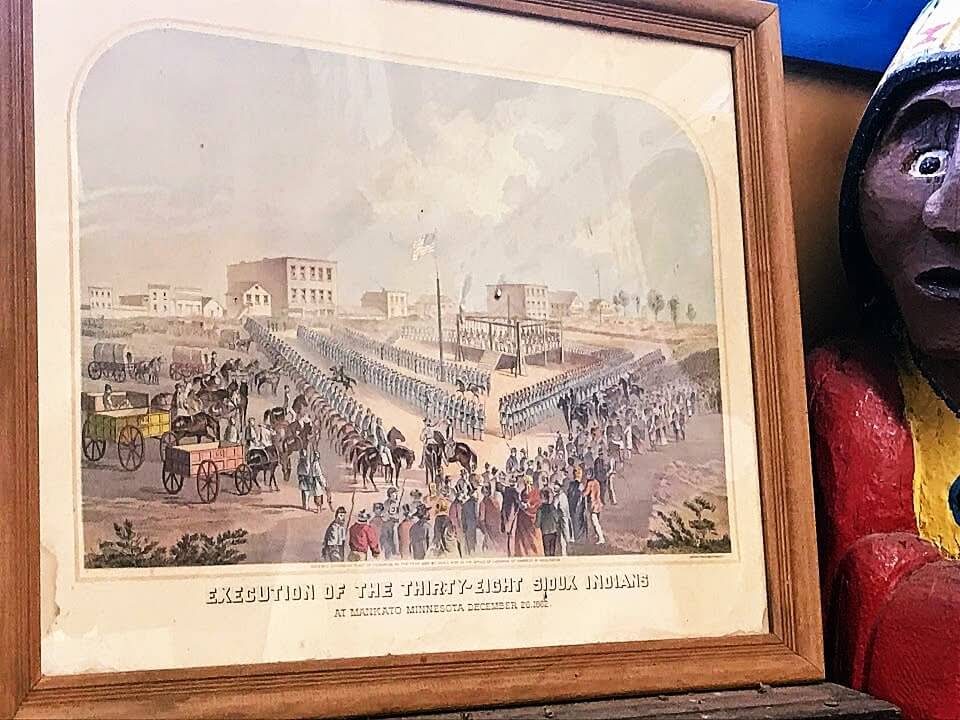

“It was an awful sight to behold. Thirty-eight human beings suspended in the air, on the bank of the beautiful Minnesota; above, the smiling, clear, blue sky; beneath and around, the silent thousands, hushed to a deathly silence by the chilling scene before them….”

—“ THE INDIAN EXECUTIONS” New York Times, December 26, 1862

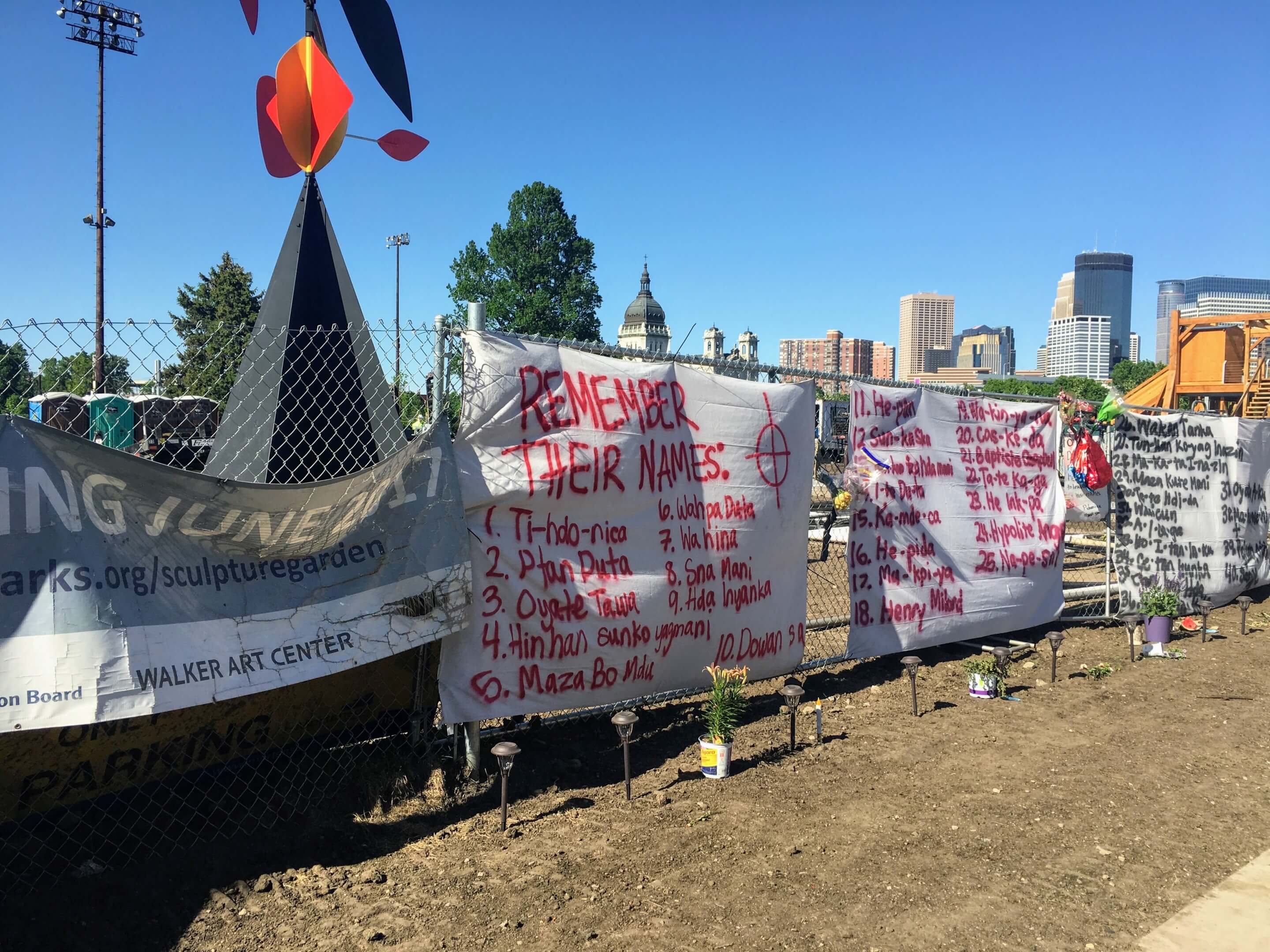

“I think it should publicly be taken down so we can see it come down. It’s really traumatizing for our people to look at that and have it just appear without any warning or idea that they were doing this. And it’s not art to us.”

—Sasha Houston Brown, Dakota tribal member, protesting Scaffold in Minneapolis. Star Tribune, June 1, 2017

In May 2017, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis landed in a public relations disaster over the installation of an outdoor wooden sculpture. The entire incident could have been avoided if the Walker’s curators or Sam Durant, the Los Angles-based sculptor they had commissioned, knew anything about the catastrophic federal “Indian Removal” programs in the 19th century.

Like other curatorial elite of American art museums, many of the Walker’s staff were trained on the East Coast or in Europe. They knew little of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 that was sparked less than 100 miles away when federal agents failed to fulfill treaty obligations with promised food, provisions, and blankets.

After a devastating winter of cold and starvation in 1861-2, warriors of the Dakota Tribes in southwestern Minnesota attacked newly-established towns near the Minnesota River Valley—Hutchinson, New Ulm, Redwood Falls, and others. Hundreds of settlers were killed or displaced. Yet, even with the Civil War raging, the newly recruited Minnesota 10th Infantry made a swift and crushing response; and the brief U.S.-Dakota War was over, soon to be forgotten by white citizens. At the war’s conclusion, Governor Alexander Ramsey ordered the “removal” of all Dakota peoples from the newly formed state.

Three-hundred-and-thirty-nine Dakota men were sentenced to hanging. President Lincoln commuted the death sentence for many—eventually leaving the “Dakota 38”—the group of men hung in a public square in the town of Mankato that December. The event remains the largest federal execution in history. In addition, 1,500 Dakota elders, women, and children were confined and forced to march in the winter to a concentration camp named near Fort Snelling, 65 miles away.

Almost exactly 150 years after the Mankato executions, curators from the Walker Art Center encountered Sam Durant’s wooden installation Scaffold at a European Art Fair. Resembling a children’s play structure, the work portrayed the gallows used in seven prominent hangings throughout American history—including those used in the executions of the abolitionist John Brown as well as Sadaam Hussein. The Walker commissioned a new version to be built at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, then under renovation. Both Scaffold installations depicted the platform gallows used for the hanging of the “Dakota 38” in Mankato.

No Native tribes in Minnesota were consulted in the selection, siting, and interpretation of Durant’s work. To make matters worse, the Walker placed Durant’s Scaffold—politically instructive for adults yet enticingly climbable for kids—next to an artist-designed mini-golf course planned for fun.

On May 26, 2017, the Walker introduced to the media the new sculptures installed in the Garden for its reopening. Only then was the true meaning of Scaffold revealed. A week-long Native occupation and protest immediately began at the site, plunging the Walker into a contemporary art center’s worst nightmare.

Why We Never Knew

Why did it take tribal occupation at the Sculpture Garden and a week of national media attention to bring this dark history to light for most Minnesotans and their arts leaders?

No matter what their educational background, few Minnesotans were taught the full history of the state’s founding in 1858 and the forced removal of the Dakota in 1862. Ever since the Civil War, few Midwesterners (including myself), ever heard this story. It was not part of the “Official History” that we learned in school, from the triumphal march of progress extending from the 17th-century French explorers, Jean Nicollet and Jacques Marquette, after whom major downtown Minneapolis streets are named, to the fur trade, statehood, the advent of railroads, and the flour milling industry.

We never learned that, in the 1850s and ’60s, such Minnesota towns as Mankato, Hutchinson, New Ulm, Sacred Heart, and Milford emerged at the edge of the frontier of the U.S.’s Indian Removal policies. These towns grew out of temporary borderlands, sites of cultural contact, and contested space. The town of Gopher Prairie, famously satirized in Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, could have been any one of them.

These new towns and county seats marked the front line of national expansion in Minnesota. They anchored an ongoing wave of settlement enabled by railroads, land treaties consistently broken, and tribal expatriation. In grade school through high school, Midwesterners never learned why, after the devastating winter and starvation of 1861-2, these frontier towns became natural targets for reprisal.

As the military quickly occupied the battle zone across southern Minnesota, the complete removal of Dakota culture from the state was soon ordered to appease terrified and enraged settlers seeking revenge. On September 9, 1862, Governor Alexander Ramsey proclaimed to a special session of the Minnesota legislature:

Our course, then, is plain. The Sioux Indians [sic] of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the State. If any shall escape extinction, the wretched remnant must be driven beyond our borders, and our frontier garrisoned with a force sufficient to forever prevent their return.

In promoting this “driving out” and extermination of the Dakota, Ramsey, who served as governor (both territorial and state) and U.S. Senator, is remembered through his Second Empire stone mansion and grounds maintained as a museum by the Minnesota Historical Society—an institution that he founded. Ramsey’s name lives on as Ramsey County, home to the state’s Capitol city, along with the names of towns, parks, and schools. The story of his murderous proclamation is far less known.

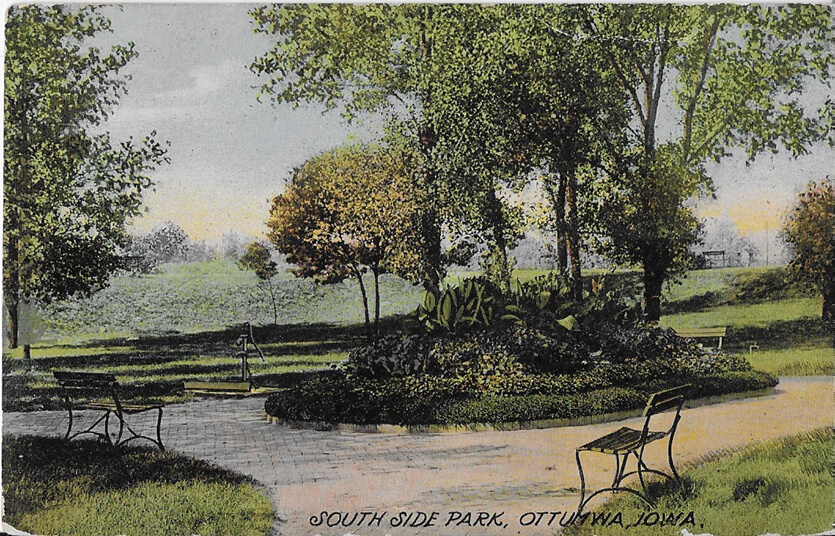

Architecture and landscape tastes played an ideological role in this colonial history of invading, removing, building, and forgetting. In the following decades from 1870 to 1920, as if to proclaim their arrival on the stage, many former frontier towns that had been attacked built some of the state’s most ornate and large park systems based on Euro-American landscape tastes. The fact that so many parks, pleasure grounds, and exotic gardens grew up in a conquered borderland landscape is no coincidence.

Focusing on the seemingly benign topic of Midwestern small-town parks and landscape architecture, we should ask how they subtly facilitated the expanding American Empire’s control of memory, time, space, and erasure in the advancing frontier. All too rarely has this aspect of American landscape design been considered through such an ideological lens.

By studying how East Coast landscape architectural fashions diffused into the vernacular parks, public landscapes, and neighborhoods in new Midwestern towns, we can ask how Euro-American landscape tastes became tools for dominance over, and erasure of, the cultures and landscapes that had been there for millennia.

Landscape Architecture as an Ideological Tool

Even the most pleasurable and seemingly benign civic acts can be expressions of power over space. Landscape architecture and park building in the Upper Midwest of the late 19th century should be reconsidered for their true ideological impact—as subtle, unconscious, and lasting assertions of conquest, ownership, and destiny.

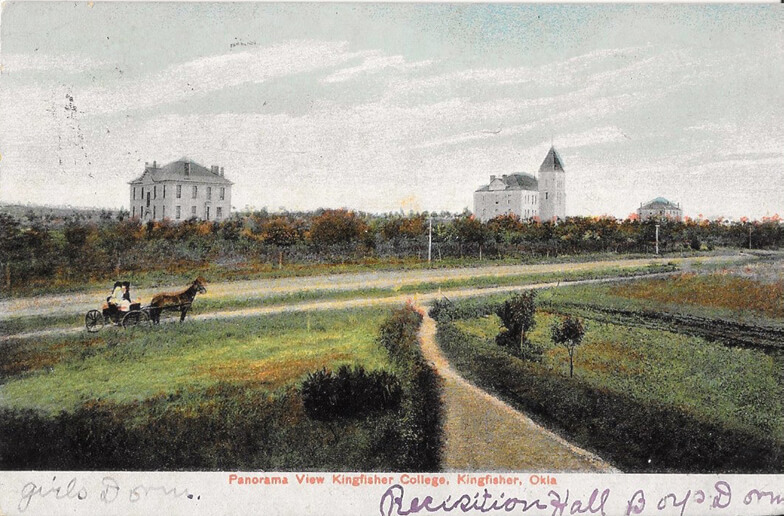

Just a few years after the containment and removal of the indigenous people, settlers rolled out a new landscape veneer alluding to their own origins on the East Coast, the Ohio Valley, and Europe. By the 1890s, new courthouses, colleges, monasteries, and state hospitals strengthened the nationalization of the Great Plains.

Often the least noticed and most taken for granted details of material culture and the vernacular-built environment intersect with larger myths of national identity and evolving signifiers of social status and control. In the 19th century, English landscape visual narratives and tastes in the Picturesque, the Beautiful, and the Sublime influenced the painters of the Hudson River School along with the landscape design of Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-52) who practiced in the Hudson Valley and edited The Horticulturalist magazine. In 1876, the year of the American centennial, editor and poet William Cullen Bryant published the two-volume Picturesque America, a massive engraving collection of beauty spots across the country.

These mass-produced visual publications became a staple in home and public libraries—arguably America’s first travel documentaries. Garden and tree catalogs promising rapid delivery, Downing’s house plan pattern books, and the marketing of garden ornament manufacturers fed the post-Civil War craze to “civilize” the growing towns and small cities of the Midwest.

In Minnesota and the Dakotas, still in the early stages of town formation in the 1860s and ’70s, these nationalizing tastes inevitably shaped ideals for home and public parks. As entirely new constructions, often built on open prairie, settlers sought a sense of enclosure and permanence.

Part of the process of colonizing the West was the civic urge to soften it. Within a generation of Native containment on reservations, new wooded grove parks, picturesque glens, and verdant town squares played a hypnotic and essential role in the erasure of their presence.

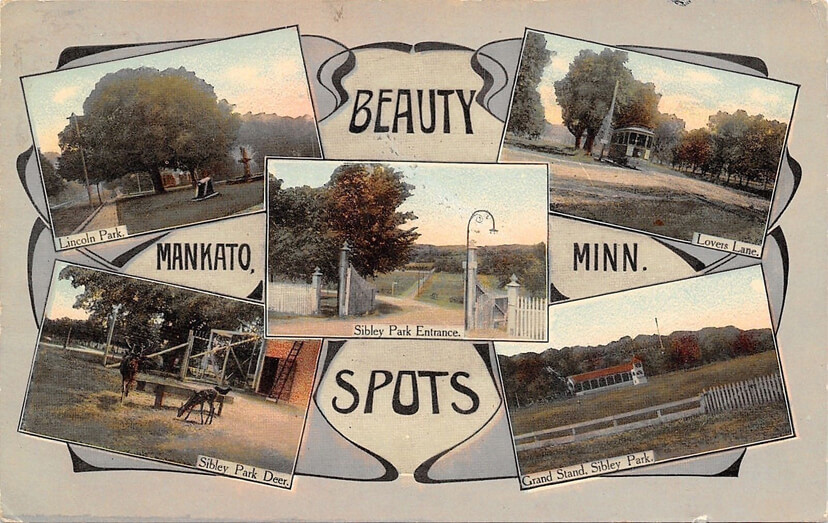

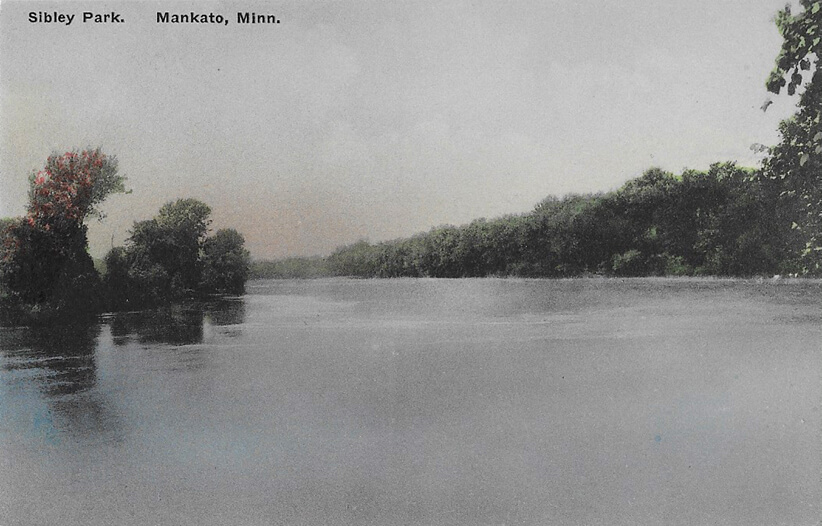

Postcards often depicted local “Lovers’ Lanes” (almost every town seemed to have one) and area “Beauty Spots”’—both constructed and natural. Both romantic place descriptions have faded from popular use today, but they were all the rage as Midwestern towns created park systems, constructed schools and streets, and boasted of their progress.

Thirty years after the mass hanging of the Mankato 38 in 1862, Mankato leaders wrote a new history through the creation of large parks and public gardens. The town promoted itself as a place of great scenic beauty and urbanity. Set along the Minnesota River, Mankato’s largest park was named after Henry Sibley, the state’s first governor and the acting general who led the state’s military response to the Dakota raids in 1862, a precursor to the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota in 1890.

Postcard Perfect: Penny Postcards and the Affirmation of American Taste

In the late 19th century, this boom in small-town park building coincided with the worldwide craze for postcards. As Monica Cure argued in Picturing the Postcard: A New Media Crisis at the turn of the Century, picture postcards were an early Tweet or Instant Message. At their peak of popularity from 1906 to 1912, billions were produced and mailed every year. They were sold everywhere, in pharmacies, newsstands, and grocery stores.

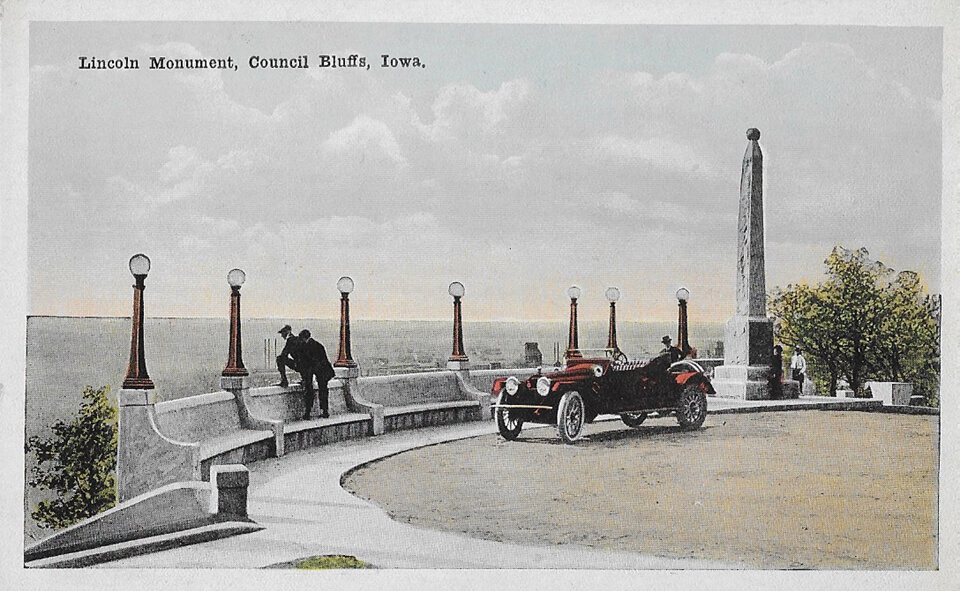

Chicago’s Columbian Exposition, a climactic celebration of American “discovery” and conquest, helped spark the postcard trend. By 1905 alone, over 7 billion were mailed worldwide with over a billion posted annually in the United States from 1905-1912. The Columbian Exposition also sparked the City Beautiful movement that fueled a generation of formalized civic improvements in small towns and cities.

New Civic Centers, amphitheaters, formal parks, and parkway overlooks brought gravitas to small towns along with an even more powerful illusion of American wealth, progress, and sophistication. This new classicism and civic pride opened entirely new postcard themes and topics.

Early 20th-century travelers often bought penny postcards at a pharmacy or train station and mailed them from the next town, or state, or after they returned home. Sometimes travelers bought postcards of towns that they never actually visited. But the very tactility and weight of the card were evidence of a location that recipient friends and family could touch. They could hold it up to the light or make a note on it of their own. Although often tinted and taken from an idealizing view, each postcard brought with it a piece of the place from which it was “taken”—the implied authenticity of having been there.

Yet even though every Main Street, central park, or county courthouse depicted was unique, their postcard stylizations, whether picturesque or neoclassical, bore a remarkable visual similarity when compared across different towns and states. Unconsciously mimicking European precedents in landscape composition and visual framing, postcard photographers captured formulaic and mythologized views of civic landmarks and points of pride. They conveyed how towns wanted to be seen—beautiful, tranquil, monumental, and growing.

Because most late 19th-century town parks seemed so “natural,” no one ever considered how artificial they really were. Certainly, no one questioned them as deeply embedded cultural constructs of landscape ideals dating back to Virgil, Claude Lorrain, Humphry Repton, and Frederick Law Olmsted that had little connection with regional ecologies.

In the upper Midwest, the consistency of a postcard’s framing and viewpoints hardly changed from the early German color cards of the 1890s to the late 1950s—as exemplified by the black and white photo cards produced by Milwaukee’s L.L. Cook Company. Such images boosted a town’s desired image and acted as promotions. But on a deeper level, they reinforced the underlying homogeneity of English landscape aesthetics, their aura of cultural superiority, inevitability and permanence.

New pastoral and formal parks, standardized house designs, and revival architectural styles re-created a familiar environment while also obscuring any reference to indigenous plants, ecologies, or human cultures. Nostalgic for distant places and times, such landscape tastes and illusions played a subliminal and legitimating role in normalizing American national dominance.

Monica Cure sees colonializing postcard view as part of a larger universe of media such as travel guides, home design guides, and national illustrated magazines. “Postcards featuring purely ‘colonial’ subjects,” she argues, “cannot be read outside the wider postcard network. Because it was seen as essentially collectible, the postcard cataloged and ordered the Metropole in much the same way as it did the colonies. The postcard in its new media moment was itself colonial. It sought to subsume everything into its domain and make it available to the postcard user.”

One could travel to the American “West” or the French colonies in West Africa through postcard trading and collecting. Like the Internet today, they brought an illusion of completeness, of becoming a catalog of everything that there was to learn about a region. But, of course, they could never convey how such colonial regions were constructed.

This privilege to selectively reconstruct a landscape and its past is an overlooked—yet essential tool in conquest. So are the persuasive and nostalgic powers of architectural and landscape fashion in legitimating a new colonial culture. Across the world, throughout the 19th-century imperial colonization, it was the conquerors’ ability to rename places, invent entirely new regions, and establish new categories for landscape classification that were the most lasting tools of indoctrination.

Reordering the World

Nineteenth-century, Euro-American imperialism linguistically constructed new countries and geographic areas. These hybrids of geographies and cultures shaped the way we still frame global wars, the saga of national expansion, and conflict zones. Nineteenth-century French colonists invented the identity of “Indochina” as a means for blending and controlling widely divergent nations and cultures. A century later, this multi-nation conglomerate became the official zone of Danger as the American public was sold the dire threat of communist expansion in Vietnam.

“‘Indochine’” is an elaborate fiction,” wrote Panivong Norindr, “a modern phantasmatic assemblage invented during the heyday of French colonial hegemony in Southeast Asia.” As a new cultural overlay, Norindr argued, “…Indochina became, for the French, a space of cultural production. While ostensibly fulfilling their mandate to civilize backward nations, the French produced a coherent image of Indochina to sustain the myth of its colonial edification.”

“At bottom, a colony is no more than an assertion of control over space backed by military force,” geographer John Zarobell asserted in Empire of Landscape: Space and Ideology in French Colonial Algeria. In French colonialism, this control required “a redefinition of territory” in “the minds of the vanquished.”

He added that, in French colonialism: “… for a colony to succeed, the character of that place had to be redefined. El-Djezaïr had to become Algiers, the widening area of control had to be circumscribed through borders, and a new name had to be invented: in this case, Algeria.”

Hidden Framing

On the other side of the world, the very concept of the American “Frontier” and the naming of settlement regions grew out of similar imperialist cultural constructs. During the 1870s and 80s, national publications such as Harper’s Bazaar, The Atlantic Monthly, and The Nation brought written and visual stories from the recently opened “Northwestern” frontier to the American public. Maps, etchings, and articles transported the reader over great distances to Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas. Later, the printed postcard celebrated this “new” American landscape for those far away.

Well into the 20th century, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Iowa defined their location as the “Northwest” even though these states were by then located in the middle of the country. Rather than conveying the upper Midwest’s geographic position, this new identity posited a location relative to major East Coast cities where the nation (and its power to expand) began. From British imperialism, we inherited similar naming conventions in “the Mideast” and “the Orient.”

Minnesotans of my generation recall a vast number of local businesses and institutions that went by that monikers: Northwestern National Bank, Northwest Airlines, and WCCO Channel 4, the Minneapolis CBS affiliate whose slogan was: “Television 4 the Great Northwest!”.

“The Northwest” was an ideal promotional tool for travel promoters, riverboat owners, railroads, real estate investors—all commercial beneficiaries of federal land acquisition and control. By the time Upper Mississippi Valley became the “Northwest”, the fate of the indigenous groups who were living there was already sealed. Today, hundreds of Minnesota businesses still retain “Northwest” as part of their name.

While place names and land can be appropriated, their indigenous cultural meaning and experience cannot. The generations of immigrants from northern Europe, New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and Ohio who built new Midwestern towns and bought postcards never understood how the tribal groups that they displaced experienced the land, their sense of seasonal time and movement, or their range of cultural and linguistic tribal variation.

Euro-American arrivals never understood that most Native Americans had an entirely different sense of land “ownership”—because most them could not conceive a world not based in English Common Law, the right to property, and geographic surveys.

The “West” and its shifting frontiers became cultural inventions. They became, for speculators and railroads, convenient short-hand place names, arguably similar to today’s marketing brands, to gloss over and promote divergent regions, peoples, and ecologies.

Freeze-Framing Genocide

For the essay compilation In The Footsteps of our Ancestors: The Dakota Commemorative Marches of the 21st Century, Amy Lonetree recounted the critical value of the 2004 Dakota Commemorative march that traced the original 19th-century forced journey from Mankato to Fort Snelling. “The larger American society,” she wrote, “encourages us to seek closure; it tells us not to ‘live in the past’ but rather to embrace a quick moment of reconciliation with the descendants of the perpetrators of the violence in our history, and then to move on…”

Memorials, designated historic sites, and museums often support cultural erasure by bracketing out the darker acts of famous people like Alexander Ramsey and treating past genocides and cultures as completed stories. By freeze-framing events, we create a sense of distance and reify once-living stories and memories as objects and completed stories.

Waziyatawin Angela Wilson, editor of In The Footsteps of our Ancestors, noted in the book’s opening chapter that: “… scholars write from the perspective that, though unfortunate, the damage has been done, as if there were only one window in time for justice to occur. Though much useful information may be gleaned from their analyses, such scholarship remains ultimately disempowering to the Dakota population because it rules out present and future justice.”

More than monuments and exhibits—commemorative marches, storytelling, and new group events help to keep alive critical messages from the past. In response to revisionist historical scholarship of the last forty years, many Minnesota museums and site interpretive materials now acknowledge the Native American side of the story at U.S.-Dakota War sites. But their well-intended presentation of maps, paintings and images represent this history as a series of acts that cannot be undone, as sagas with little impact on life today.

Curators at the Walker Art Center followed this paradigm in commissioning an artwork to cast the killing of the “Mankato 38” as a largely forgotten hanging that could be interpreted in the context of other American hangings. They misjudged, to use writer Vivian Gornick’s terms, the Situation and the Story.

Sam Durant framed and situated this tragic event as one of several hangings. He sited their combined representations in a sculpture commissioned by the Walker for a garden. He stated that Scaffold was meant to convey a message of historic violence and inequality to a white audience. What Durant and curators missed was the narrative of the acute enduring pain, fear, and anger surrounding this hanging, this singular story for the Dakota people. For them, the Mankato hangings were not just part of some larger outsider catalog of executions.

(Editor’s note: After the debut of Scaffold, Sam Durant avoided erecting other large-scale public installations until the recent reveal of Untitled (drone), which will be installed on New York City’s High Line later this month.)

For artists and historians, the situation of the public hanging in Mankato can be represented in a lithograph, art, or prose. But it was Indigenous people’s intergenerational and visceral memory of this story that sparked the occupation of the Scaffold site, and later the project’s dismantling and burning in an apology from the museum.

Like the blossoming of protest art that emerged in the Twin Cities after George Floyd’s murder in May of 2020, many critically powerful vestiges of social unrest, resistance, and inequity are ephemeral and not physical objects and artworks at all. By assigning historic value only to embodied buildings, cities, ruins, and great leaders cast in bronze, Euro-American historical curation continues to overlook stories like the brutal federal response in the U.S.-Dakota War that was supported by many of my settler ancestors in southern Minnesota and St. Paul.

In 1987, I finished three years of graduate school in landscape architecture at the University of Wisconsin. The focus for my degree was the field of “Cultural Landscape Preservation and Landscape History.” We studied histories of European settlement across our region focusing on European-American folk/vernacular building types, rural midwestern landscapes, small-town Main Streets, and historic preservation theory. Never once during that time did we discuss Native American history or its memory in our region.

I first glimpsed the Indigenous side of the “Dakota Uprising” eight years ago when a Native American historian took a group of fellow educators to Pike Island, named after an early 19th-century explorer who made the earliest land transactions with the Dakota.

Here was the site of the 1862-3 Concentration Camp where roughly 1000 Dakota women, children, and elders died of starvation, winter cold, and disease. We stood together in a floodplain forest as he recounted what happened there.

The Dakota still know this broad valley at the junction of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers as Bdhote—the sacred land where human beings first entered into the world. Bdhote is also the place where hundreds perished after the Mankato hangings—soon to be forgotten and erased by American settlers who built a cultural landscape entirely of their own.

Frank Edgerton Martin is a landscape historian, architectural writer, and design journalist. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Philosophy from Vassar College and a Master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin, Madison in Cultural Landscape Preservation and Landscape History.

Martin served for many years as a regular contributor to Landscape Architecture magazine and other publications, covering projects across the country, design history, and campus planning. He currently serves as a regular architectural columnist for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune.