Central East Austin, the Texas capital city’s historically Black neighborhood, has managed to preserve its wealth of cultural and historical assets in the face of a sustained wave of gentrification that’s reshaped the area in recent years. Among others, these assets include: the campus of Huston-Tillotson University, an HBCU established in 1875; the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP)-listed Victory Grill, one of the few remaining Jim Crow-era juke joints on the legendary Chitlin’ Circuit; Rhapsody, a 50-foot-long mosaic mural at Charles E. Urdy Plaza celebrating the rich heritage of the community, and the Dedrick-Hamilton House, a restored circa-1880 home, now part of Austin’s African American Cultural & Heritage Facility, built and owned by Thomas Dedrick, one of the first freed slaves in Travis County.

There’s also the George Washington Carver Museum, Cultural and Genealogy Center, a multifaceted facility—one part museum, one part community center—established in 1980 in the heart of Six Square – Austin’s Black Cultural District as the first African American neighborhood museum in Texas. (Six Square refers to the size, in miles, of the “negro district” established by the City of Austin in its notorious 1928 city plan that institutionalized racial segregation.) While all of Central East Austin’s Black landmarks maintain their own unique ties to the past, the Carver Museum stands apart as a historical repository and a forward-looking community resource. In a rapidly changing neighborhood in a rapidly changing city, the Carver Museum is an enduring cultural axis binding Central East Austin.

Considering the multiple hats worn by the Carver Museum, it’s no surprise that the Austin Parks & Recreation Department-owned and -operated facility, which, in addition to permanent and special exhibits offers an array of cultural programming and educational initiatives, has outgrown its current home. To meet the evolving needs and priorities of the community that it serves, the Carver Museum will undergo a long-awaited $58 million expansion plan unanimously approved by the Austin City Council on June 10, just days ahead of the museum’s annual Juneteenth celebrations. Incorporating feedback from civic leaders, neighborhood residents, and local artists, the Durham and Austin studios of Perkins&Will, along with Smith & Company Architects, partnered to reboot and reimagine a never fully realized expansion plan from 1998.

“Instead of going in and implementing phase two, because it was so long ago, the City of Austin decided not to continue on with the master plan they already had and felt the need to do a new one,” explained Terry Smith, founder and principal of the Houston area-based Smith & Company. “The players had changed and so had the neighborhood.”

From segregated library to community staple

While the present-day Carver Museum has been around for a little over four decades, the original museum building, a modest colonial revival-style structure listed on the NRHP since 2005, dates back much further.

In 1933, the building, constructed several years prior opposite Woolridge Park in downtown Austin as the city’s inaugural public library, was relocated to 1165 Angelina Street in East Central Austin. Here, it reopened as a segregated branch of the Austin Public Library system serving the city’s Black community.

In 1947, four years before the integration of city libraries, it was renamed the George Washington Carver Library after the famed African American agricultural scientist. The aging, brick-clad building remained a public library branch until 1979 when a larger modern facility was completed immediately next to it. The original library was then converted into a new facility known as the George Washington Carver Museum.

Nearly 20 years after the Carver Museum debuted in 1980, a 1998 bond funding measure was approved for a facility expansion and a three-phase building program was developed two years later. Five years after that, in 2005, the first phase of the expansion opened to the public. Housed in a crescent-shaped structure designed by Donna Carter, a Black Austin-based architect, the new addition brought a 134-seat theater and lecture hall, classrooms, dance studio, archival space, exhibition galleries, and more to the growing museum campus adjacent to the public library, which also expanded in 1998, bearing the same name. The original historic library-turned-museum building was subsequently converted into the Genealogical Center.

As for the second and third phases that would have seen the roughly 36,000-square-foot Carver Museum expand even further, they eventually fell to the wayside and the allocated funding was siphoned away for other projects headed by the city’s parks department.

“I wouldn’t say it was a full-blown master plan, but it was always intended to expand,” explained Stephen Coulston, Urban Design Principal at Perkins&Will’s Austin studio, of the never-realized subsequent phases following the 2005 completion of the new museum building.

“That was nearly 20 years ago,” Coulston added. “And there are people from the community who were a part of that first building process and the planning effort after that who really want to see this thing come to life.”

A belated growth spurt at just the right time

In 2019, ahead of both a global pandemic and a historic social justice movement sparked by the murder of George Floyd, city officials gave the green light to the expansion planning process, which formally kicked off (entirely virtually) in April of 2020.

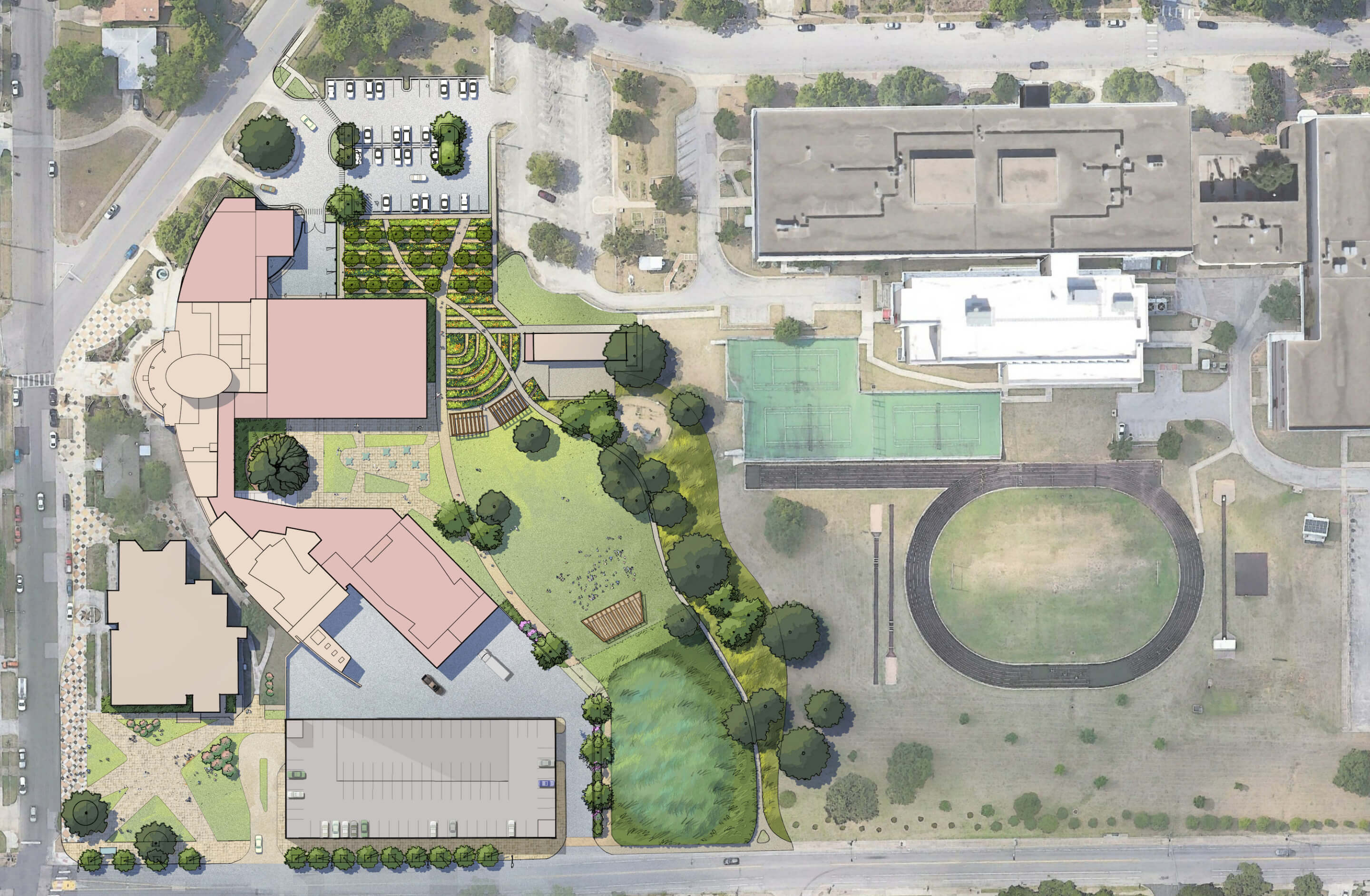

The Austin City Council approved the plan, which envisions the Carver Museum’s footprint more than tripling in size to over 90,000 square feet, this past June.

Included in the expansion plan are two floors of dedicated exhibition and education spaces, a special events ballroom, and a sizable new theater with room for 500. Also proposed is a large new parking structure.

In addition to documenting local history and showcasing contemporary Black art and culture in Austin while advancing the mission of the museum, one of the key goals to arise from a series of three virtual community engagement sessions—a particularly salient one given the COVID-19 crisis—was to create outdoor amenities that connect with nature in what Coulston called a more “more deliberate and purposeful way.”

To that end, the museum campus, which is adjacent to a large park, will gain a sprawling social lawn anchored by a pavilion for outdoor concerts and other performances, a community garden, exterior classrooms, a “Black Austin History Sculpture Walk,” and a new Juneteenth Plaza at the southern corner of the complex, at the intersection of Angelina and Rosewood Streets.

Although the Carver Museum, run by the parks department’s Division of Museums and Cultural Programs, already hosts outdoor events, the current site facilities simply “weren’t designed to support them,” Coulston explained.

“What if we understood programmatically what it is you’re trying to achieve, and designed a space to actually support your program, as opposed to you trying to shoehorn a program into what you have available?” said Coulston of the approach, adding that features like an outdoor kitchen and amphitheater for open-air performances “became more and more crucial as a part of the conversation in the middle of COVID when people are much more deliberate in terms of embracing the outdoors.”

An anchor to the past

Embarking on an all-virtual planning process during the throes of a global pandemic required adaptability and improvisation. As Coulston explained, things went as smoothly as it could have considering the challenging circumstances. “Everything that you could possibly throw at it from a local, national, and global impact perspective happened over the course of this project. But I think that people were happy to have a venue for conversation.”

The initial phase of the three-phase project will focus on renovations at the existing museum building along with site improvements and building out new outdoor spaces such as the event lawn and plaza. Subsequent phases will deliver the exhibition/education wing, the ballroom, and, in the final phase, the theater and parking structure.

Funding for the Carver Museum campus revamp, which Coulston referred to “as a City of Austin project, but also a cultural and community resource for the entire region,” is expected to come from a mix of private and public sources, including corporate partnerships, grant opportunities, parkland dedication funds, and more. “We really phased the long-term plan to be incrementally implementable in bite-sized pieces,” said Coulston.

East Central Austin isn’t unique in the fact that it’s a historically Black neighborhood in the urban core of a major city to be, in the words of Smith, “vastly impacted” by gentrification in recent decades, including the real estate-driven displacement of families who have lived in these neighborhoods for decades.

“Generations of people have moved out of these neighborhoods and taken the history and the culture with them,” explained Smith. “And so, projects like this one are happening all over because communities are saying: ‘We’ve got to do something to anchor that history in this neighborhood or else younger generations will have no idea that these neighborhoods were once this historic, and once this culturally connected.’”

“And that,” Smith said, “is why the Carver Museum is so crucial.”