The most influential piece of self-identified Brutalist architecture in recent history was built in 2019 and it welcomes over one million visitors a year. Referred to as simply the Oldest House, the monolithic Manhattan skyscraper is the backdrop in which the popular video game Control takes place. Developed by Remedy Entertainment and published by 505 Games, Control’s depiction of architecture gives us a strong reading of contemporary sensibility and desire. This merits taking the Oldest House seriously as an architectural object in its cultural context. From my visits, the spaces in this game are a triumph of formulation, but to understand what that cultural context actually is we must first ask: Why is Brutalism so trendy right now?

The internet loves Brutalism. From Instagram accounts like @cats_of_brutalism to The Brutalism Appreciation Society on Facebook and even Brutalism TikTok, images of sensual concrete architecture continue to captivate audiences. Hang out long enough on any of those platforms and you’ll find people also love to argue about just what exactly counts as Brutalism almost as much as they like to look at the stuff, which makes sense because Brutalism isn’t a well-defined holistic architectural approach but is better understood in contemporary terms as an aesthetic compulsion. The stark material qualities, harsh light, and striking features in the work of Alison and Peter Smithson can also be found within a long list of historic trends: Russian Constructivism, Early European Modernism, and even a dash of Japanese Metabolism. As a constituency, it isn’t an architecturally self-identifying concept, it’s more of a vibe.

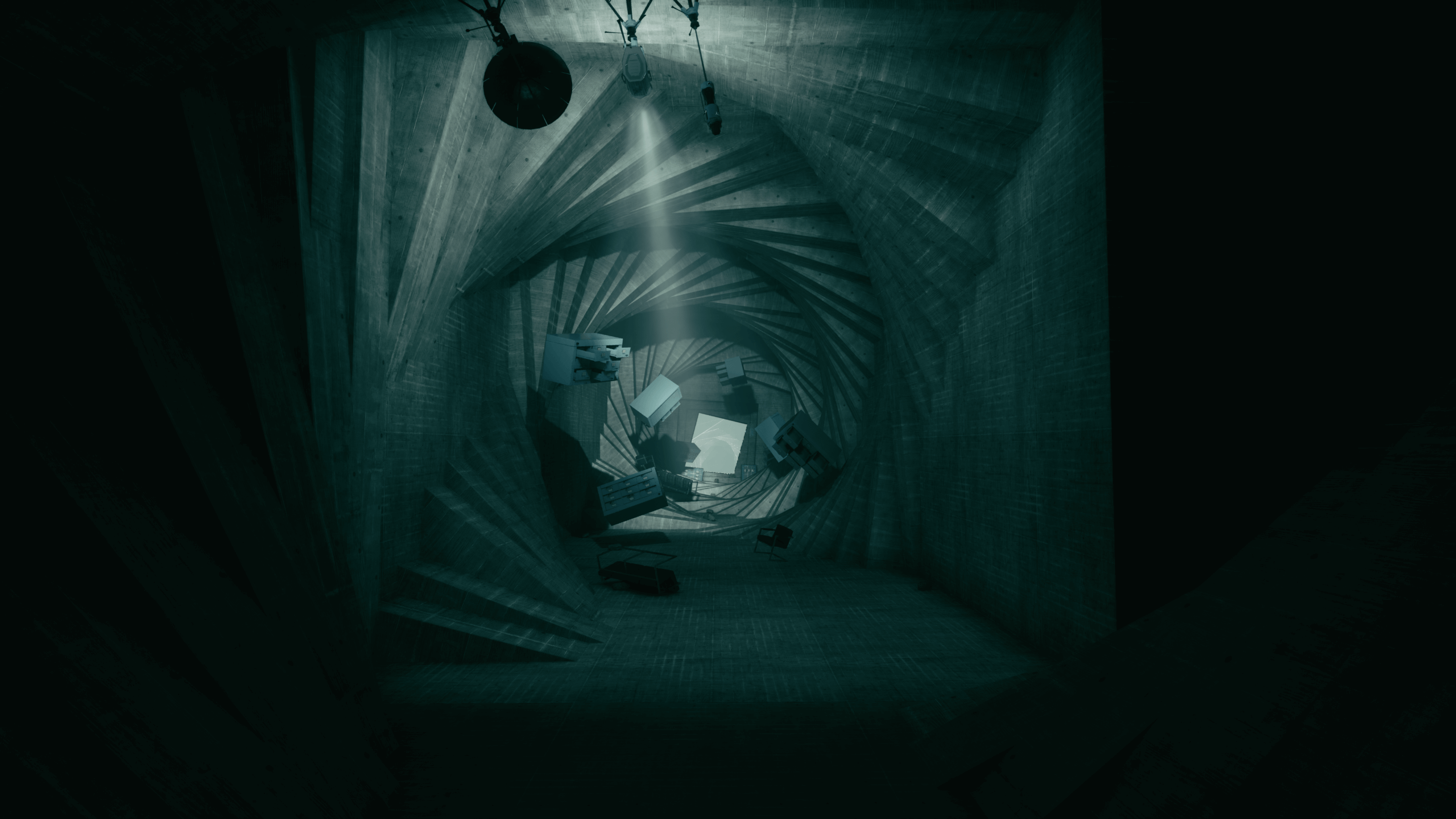

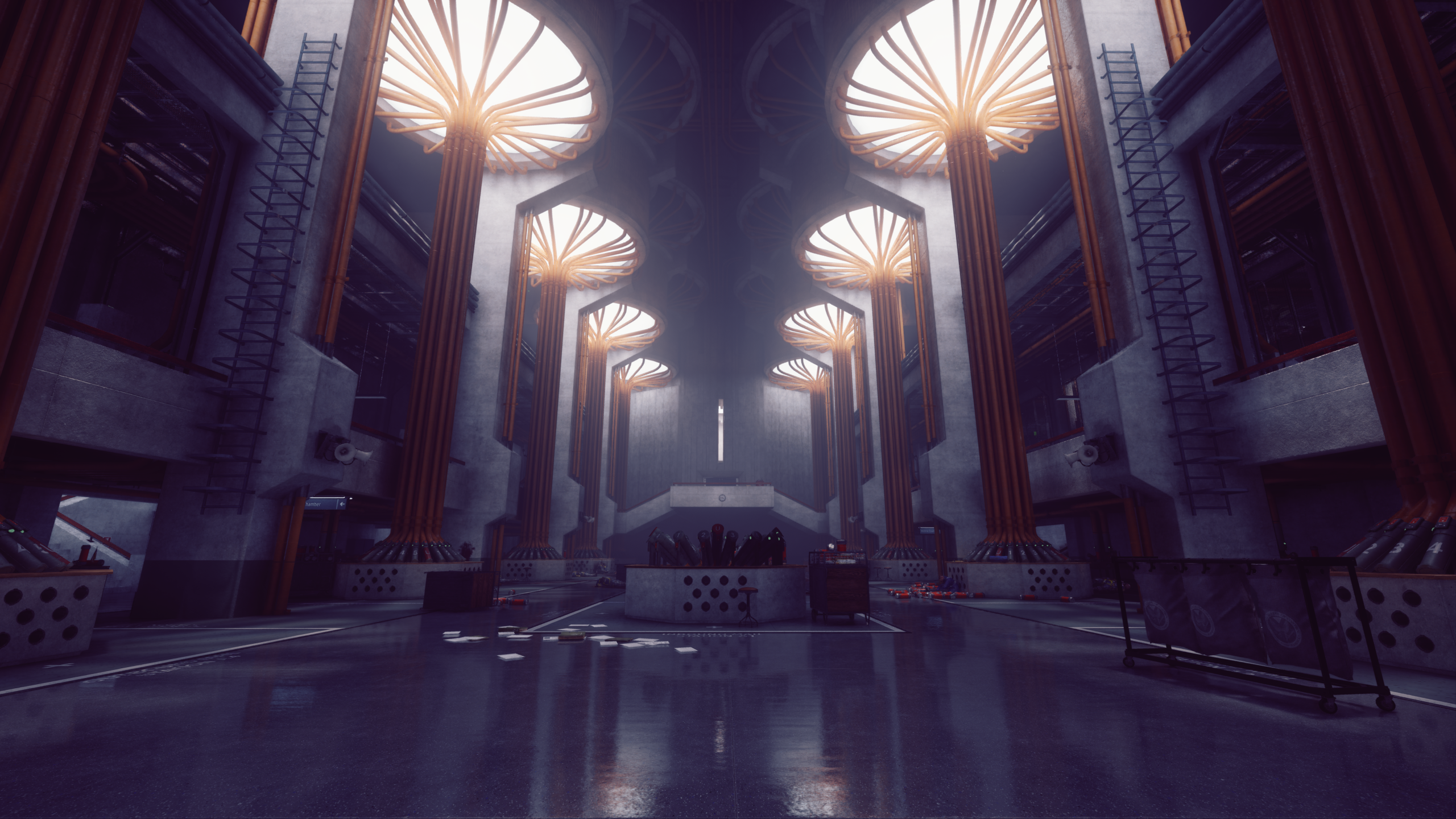

Nothing took better advantage of this cultural vortex than Control, which takes its name from the in-game Federal Bureau of Control, the paranormal research arm of the U.S. government that calls the Oldest House home. You play as Jesse Faden, the newest director of the Bureau. The building is the contemporary analogue of a haunted house; due to its digital form, the building itself can shift and move as if it is alive (something explicitly implied by in-game lore). The building is a character with its own impersonal shadowy autonomy, but the player’s role is to purge the house of an infection caused by a hostile supernatural force called the Hiss. The alienating and muted spaces of the building create an unforgiving environment, rendering the exact obstacles you are facing and their goals unclear. Are you fighting the house itself or its infection? Is the house my enemy or my ally? The Oldest House’s cherry wood handrails with brass inlays become projectiles; when struck with bullets, the board-formed concrete comes off in chunks that float around Jesse, creating a wall of defense against enemies. Its multilayered mechanical depths become dungeons ripe for the cleansing. Even the hulking, massive pneumatic letter chutes in the mailroom that intertwine and grow to form multistory “trees” become cover against bombs and missiles directed against the player. Director Faden’s ability to temporarily suspend gravity allows the player to float inside the large vertical spaces and explore the stacked layouts typically inaccessible in comparable games. All the while, the Oldest House’s impersonal disposition to my presence perfectly illustrates the desired effects of its architecture.

The game never explicitly states a location for the building other than New York City, but the few exterior glimpses given to the player are strikingly similar to a conspiracy theorist favorite: 33 Thomas Street in Manhattan. Widely speculated as the likely location of the NSA mass-surveillance project called TITANPOINTE, the building in the game is a skyscraper, yet the levels and spaces are wider than they are tall. Additionally, the Oldest House is implied to have existed since before mankind and can’t be seen at all from the outside under normal circumstances. To explore this, I asked Kent State University student James Moss to create a speculative drawing where the game space would exist if it were superimposed onto the real world. Imagine standing at the corner of Church and Worth in Tribeca and seeing a conceptual space floating above your head that over 2 million people have formed a close relationship with.

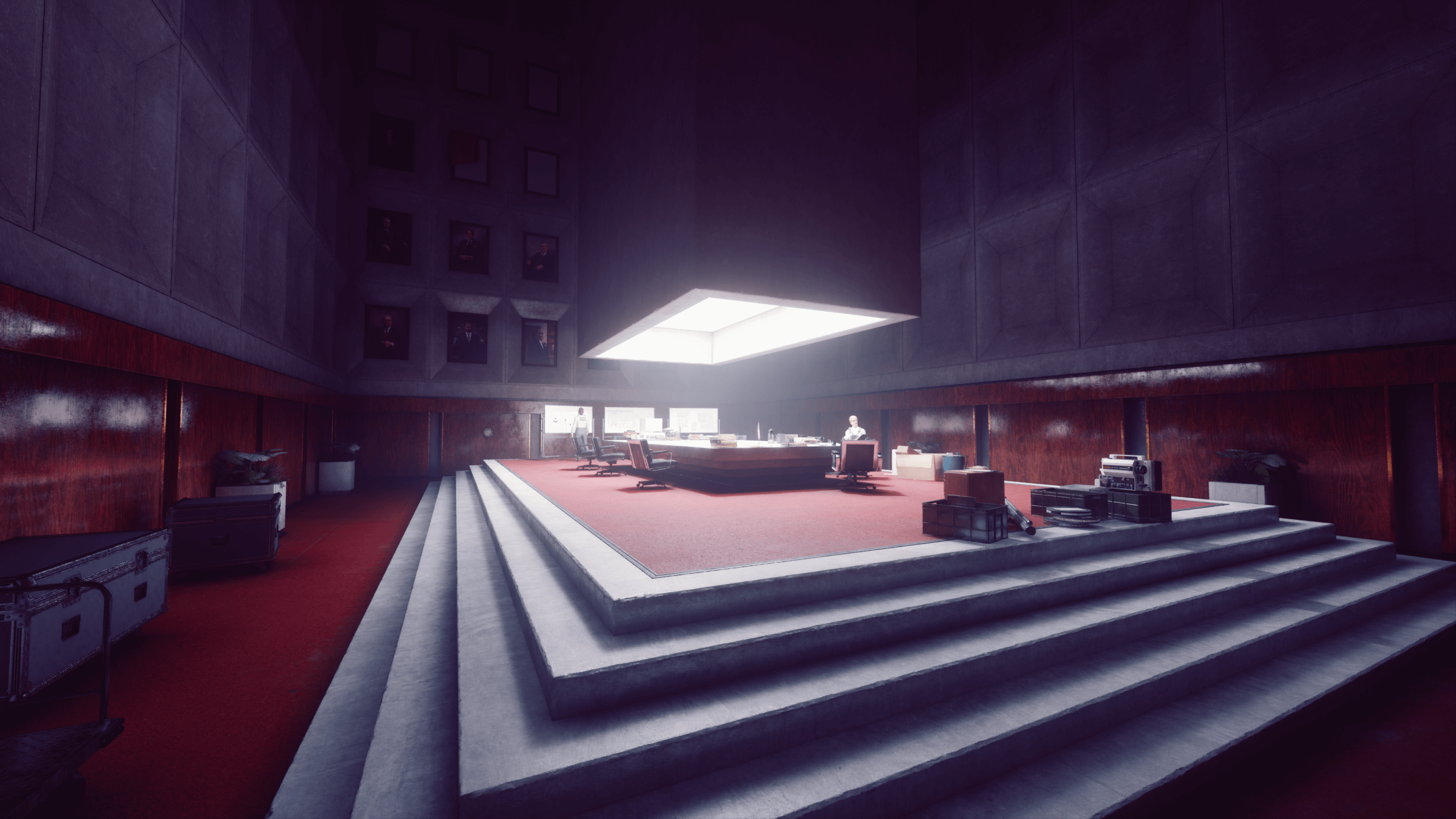

During the action it is hard to recognize the architectural elements, but between bouts the player’s eyes rest on the sensual loneliness of a low-pile orange carpet and half-dipped brass bulbs. Seen out of context, a raw concrete wall bathed in directional light can be rather stirring, as the source and intention of those effects are unknown—especially as the Oldest House is fortified and receives no natural light. On the topic of Brutalism, Remedy art director Janne Pulkkinen explained in The Art and Making of Control that, “it was important for us to have some believability there as a backdrop for all the supernatural weirdness that was going on, because it doesn’t really work otherwise.” In other words, the team had to create an architecture that feels real and familiar to many different people, yet unfamiliar enough so that it’s not specific enough to peg to a real-world location. To accomplish this, the game borrowed liberally from a host of familiar architects like Marcel Breuer, Paul Rudolph, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Carlo Scarpa, tweaking the work ever so slightly to leave just a sense of familiarity behind every turn. Suddenly, what was billed as Brutalism is now too broad a mashup of styles to label as such.

Interrogating the specific instances of the sampled architecture reveals the game is about more than just Brutalism. In Control, the Bureau refers to the Oldest House as a “place of power,” a paranormally significant structure that acts as a nexus to potentially infinite alternate realities. The game signals this property by centralizing each space you visit, which is codified through mass, structure, depth, surface, repetition, and symmetry. Combined with the borrowing of so many varied works, this results in an architecture that’s less a vague commentary on Brutalism’s ability to overwhelm or alienate, but more about institutionality—even the midcentury, Mad Men–style office furniture reinforces the banality of the bureaucratic work that typically goes on in this eldritch structure. This desire has been achieved not only in video games but in recent films and television shows. The same institutional vibe of the Bureau of Control is given off by the Time Variance Authority (TVA) in the new Disney+ series Loki. On the show’s captivating visuals, production designer Kasra Farahani said that “because the TVA is a bureaucracy and I think, archetypically, so much of what we know a bureaucracy to be is that post-war, highly funded institutional look.”

While each room in the Oldest House is locally centralized, the building itself is programmed chaotically. “We often ended up looking at churches, because they’re typically symmetrical… there are actually a lot of altars in the game,” Pulkkinen again noted. The floor plan of each area twists and turns, and entire sections of the building regularly become unmoored and reappear elsewhere. Through the eye of the player, all authority is only perceived locally, lacking overarching organization. Thus we are struck with an even more terrifying reality: the Oldest House has no singular authority at all, but instead is a series of defamiliarized authorities all mashed up in one building, even down to its seemingly harmonious architectural style. Throughout the game, the player slowly realizes that despite the familiar board-formed concrete look and sleek modern furnishings, all of the human interventions are futile attempts to impose order on what amounts to a living organism—when the true foundations of the building are finally breached, it’s not a basement but an ancient series of caves that sprawl out below the Oldest House like a root system.

One can only speculate why conditions of empty and foreboding architecture of authority have come to increased mainstream popularity as of late. For example, places like the Hawkins Laboratory from Stranger Things, which was actually staged at the Georgia Mental Health Institute at Emory University by A. Thomas Bradbury, and the aforementioned TVA headquarters from Loki, which dressed up the otherworldly Atlanta Marriott Marquis designed by John Portman (a popular backdrop for sci-fi movies). Control transcends the idea of Brutalism entirely and instead expands to become a dramatic display of the surprising power of narrative space. Through the expanding cultural technologies around digital space, we can begin to use architecture to engage the public in novel ways. Video games in particular provide experiences orders of magnitude beyond the original conception of digital architecture, and the rapid expansion of the medium suggests that the language and discourse of architecture itself will need to adapt to accommodate. What happens when we can’t search for singular styles in digital environments programmed to change?