In 1819, Rufus and Jane Pratt Dunham immigrated from Massachusetts to the sprawling Western Reserve, now northeastern Ohio. The young couple settled on a nearly 14-acre farm in the village of Cleaveland, a sleepy riverfront settlement established just a little over a decade before. It wasn’t until 24 years after the arrival of the Dunhams, in 1831, that a single vowel was dropped from the village’s name by a local newspaper, an editorial deep-sixing that forever altered the name of what is now Ohio’s second-most populous city.

Throughout the 1830s and ‘40s, Cleveland enjoyed a major growth spurt thanks to its official incorporation as a city and the completion of the Ohio and Erie Canal. At the same time, the Dunham farmstead expanded too, with the addition of two news wings and a taproom to the original clapboard-sided colonial farmhouse, which was completed in 1824. The addition of the tavern was a lucrative one that took advantage of the farm’s location along the old Buffalo-Cleveland-Detroit Post Road, now Euclid Avenue. The Dunhams eventually sold the property and in 1857 the establishment served its final pint as the tavern was converted into a private residence. The home, which stands today as the oldest building in Cleveland at its original site, remained a private residence through the following decades save for a period during the 1930s when it was used as a studio for Works Progress Administration artists. In 1941, the former farm-turned-stagecoach stop opened as a public museum by the Society of Collectors, a nonprofit established by the preservation-minded previous owner, landscape architect Donald Gray.

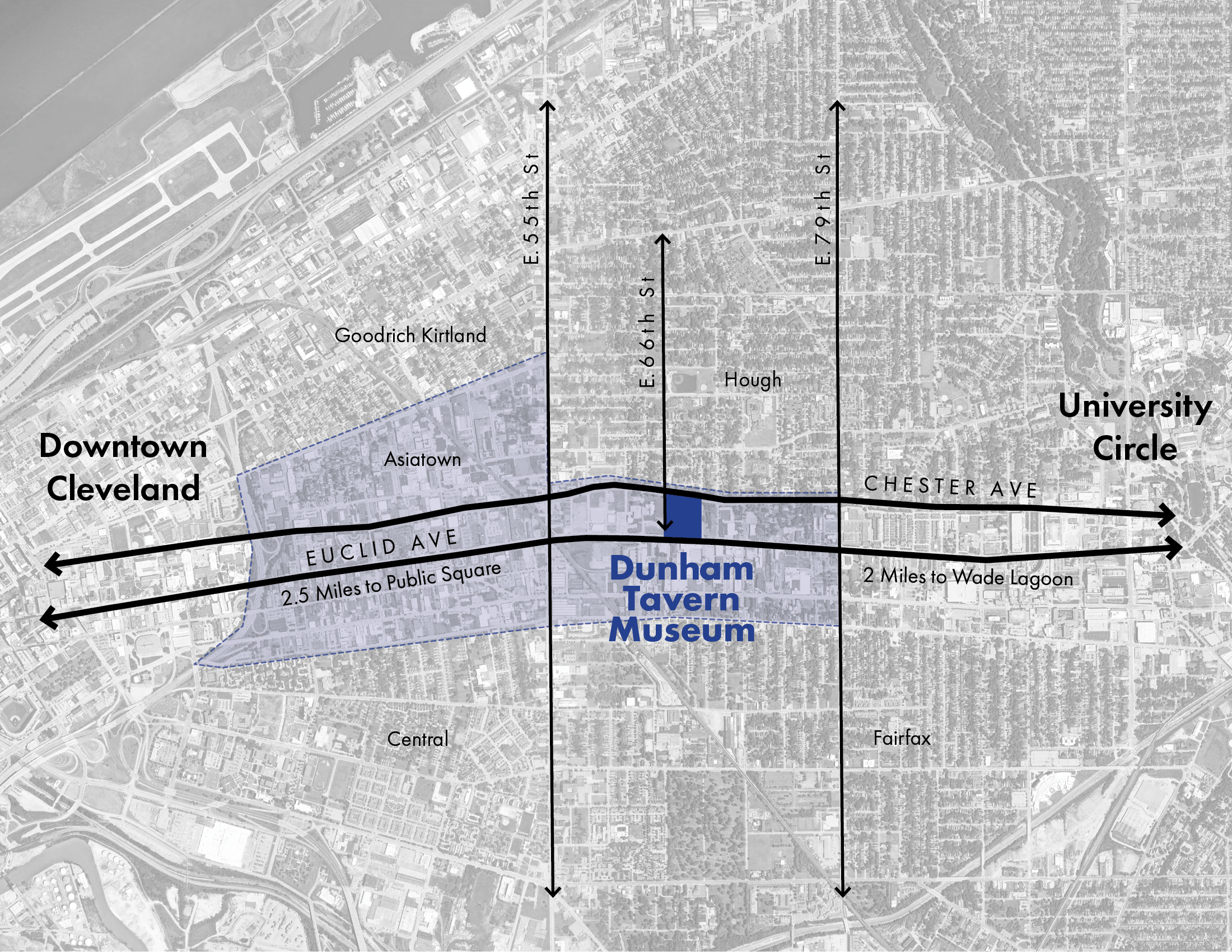

Today, the National Register of Historic Places-listed Dunham Tavern Museum spans a 6-acre campus in the Hough neighborhood on Cleveland’s east side and offers visitors an authentic—and skillfully preserved, thanks to the early efforts of Gray—slice of the Ohioan pioneer life complete with a Heritage Trail, period gardens, demonstration farm, and the antique-stuffed house museum. While Dunham’s frozen-in-ember qualities are among its greatest assets, this has also kept it cloistered from the majority-Black neighborhood surrounding it.

Describing a “kind of insularity” that has followed the museum over the years, Lauren Hansgen, executive director of the Dunham Tavern Museum, explained to AN that the larger transformation of MidTown Cleveland into a multifaceted civic and innovation district is “in perfect alignment with our own organizational goals—and that is to be a place for history and for nature, but also a community gathering place.”

“I don’t want Dunham to just be a regional cultural destination, but also an asset to the neighborhood and anchor in the community,” added Hansgen. “That means that we must deal with both physical and perceptual barriers, including literally taking down fences and cleaning up undergrowth. We want to make it obvious that there is a path into our campus and that you’re welcome.”

To aid Dunham in the repositioning of its campus into a school trip-popular historic site and inclusive community asset, the museum tapped Merritt Chase, a landscape architecture and urban design practice based in Indianapolis and Pittsburgh, and LAND studio, a Cleveland-based nonprofit developer of urban parks and public art. Together, Merritt Chase and LAND studio worked with the museum to develop a campus master plan that serves as a “framework to facilitate practical day-to-day decisions as well as communicate Dunham’s vision for the future” as an “inspiring, welcoming 21st-century public space.”

Informed by workshops, presentations, and listening and learning sessions attended by community stakeholders and Hough residents over an 18-month period, the recently completed master plan is centered around five key objectives: History, Education, Nature, and Community. It also proposes a range of interventions that preserve and enhance existing elements while creating new spaces that “allow Dunham to build upon its cultural significance and community presence.”

Enhancing the old and creating anew

While the landmarked museum and tavern building will remain largely untouched in its current location (although it is in need of maintenance work, including a new roof, as noted in the master plan), the now-vacant Banks-Baldwin House on the northern end of the campus near Chester Avenue is currently in the process of being relocated to an area closer to the museum where it will be converted into a campus visitors center, freeing up space within the museum proper.

The barn, rebuilt in 2000 after a fire destroyed the original 1840s structure in 1963, will be expanded and potentially renovated to better accommodate museum programming as well as public and private events. Meanwhile, the museum’s log cabin structure will be relocated and rebuilt just south of its current location along a revamped Heritage Trail, which itself will be expanded to form a full loop around the periphery of the campus. The existing demonstration farm will also eventually be scaled-down and relocated to the northeast section of the museum grounds. Most of the mature tree canopy across the campus will be preserved, including the farm’s existing orchard.

Other short-term priority projects along with the relocation of the Banks-Baldwin House and the Heritage Trail extension include implementing enhanced wayfinding across the campus, removing barriers and perimeter fencing, and executing landscaping improvements in key areas.

As for wholly new elements envisioned in the master plan, they include a spacious event lawn to be located north of the barn, a series of culturally themed specialty gardens (community reconciliation-, healing-, indigenous-, and local geology-focused gardens among them) along the Heritage Trail, and a roughly 3,000-square-foot Community Farm Pavilion that will support community programming and farming operations. Both the barn expansion and pavilion will feature restrooms, kitchens, and flexible gathering spaces, while the former will be anchored by a large event hall.

A matter of trust

Chris Merritt, founding co-principal of Merritt Chase, said that when the practice first came on board it become clear that Dunham, a living time capsule known for its antiques and gardens, is “in the neighborhood but not of the neighborhood.”

“This plan is a big effort to try to overcome that,” Merritt said, emphasizing that the underlying goal of the project is to have Dunham reach “new and diverse audiences—and so, redefining history for them and telling new stories was really important.” He noted the paramount role that new elements like the cultural gardens will have in the museum’s newfound embrace of the neighborhood.

As for the lengthy engagement process, Merritt noted that it was crucial not just to inform the community about “the design of the plan but to also really develop a relationship and build trust that hasn’t been there.”

And per Merritt, that trust is already improving with a milestone being this past Juneteenth, when neighborhood organizers asked Dunham if it would host a celebration marking the newly consecrated national holiday on the campus.

“This was probably the most exciting and symbolic of the changing relationship between Dunham as an organization and residents,” said Hansgen of the museum’s Juneteenth festivities. “It was stupendous.”

“We have a lot of recommendations, not just in the physical improvements on the campus,” added Merritt of the more inclusive future for Dunham envisioned in the master plan. “You also have to have that kind of trusted relationship, and the programming is really important. It can’t just be kind of an Antiques Roadshow in the museum. It’s also got to be whatever you develop with the neighborhood.”

Won’t you be my neighbor?

With the implantation of some of the Dunham master plan’s short-term priority recommendations now underway, there’s also a flurry of activity immediately west of the museum on the corner of Euclid and E. 66th Street. On a nearly 3-acre swath of land acquired from Dunham, the Cleveland Foundation is constructing its $22 million new headquarters, a three-story hybrid mass timber building designed by a Pascale Sablan-led team from New York’s S9 Architecture. (Sablan has since left S9 and is now with Adjaye Associates.)

The land in question was purchased by first Dunham from the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority following a 5-year, $700,000 fundraising campaign and involved the demolition of a long-moribund industrial building to make way for what was to be a Dunham campus extension in the form of a large public park. The future green space was then sold to the Cleveland Foundation, which was founded in 1914 as the first community foundation in the world, for its new headquarters. The move prompted a headline-grabbing 2019 lawsuit filed by former Dunham board and museum members, and, in December 2020, the Ohio Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal to invalidate the sale of the land. With that, construction work at the former brownfield site, which also required extensive environmental remediation in addition to the razing of a 1920s-era textile factory, was cleared to proceed.

Aiming for LEED Gold and eventually Platinum certification, the 54,000-square-foot Cleveland Foundation Headquarters will be seamlessly linked to the Dunham campus via open green space while a proposed east-west greenway of pocket parks and public plazas is planned for the north of the new building. This effectively fuses together the Dunham Campus and the Foundation headquarters with the larger nascent MidTown civic and innovation district. Meanwhile, a rejuvenated mile-long streetscape will extend northward along E. 66th Street to League Park, forming a proposed Black historic and cultural corridor.

“Dunham all of a sudden gets connected, structurally and recreationally beyond its own borders, into the community,” said Lillian Kuri, executive vice president and chief operating officer of the Cleveland Foundation, of the plan, which effectively knits together disparate parts of MidTown, old, new, and reborn, with open public space.

As for the building itself, its design exudes the same quality of openness as the Dunham master plan.

“We worked so hard with Pascal [Sablan] to create a building that had permeability on all four sides, which is really hard to do in an office building,” explained Kuri. “The green space kind of flows up through and you have all this interaction at the ground floor—it’s not like ‘building’ and ‘park,’ it’s ‘park’ and ‘building’ coming together. And that was important to us.”

With litigation now in the rearview, construction of the building, which in addition to offices for the Cleveland Foundation will include a public art space, cafe, meeting facilities available for nonprofit and community use, and a ground-level space populated by the Neighborhood Connections community-building program, is now underway. The building’s structural steel frame was erected late last month and, as relayed by Kuri, the project is expected to be completed next fall.

Back at the Dunham Tavern Museum, where barriers are coming down and community trust is being built up, Hansgen anticipates the possibilities of a reimagined historic house museum that caters to traditional visitors while also serving as a singular urban green space that fuses together the surrounding neighborhood.

“It’s not just the story of an old building—the story of place and land is very relevant to our identity,” explained Hansgen of the effort to broaden the museum’s “period of interpretation while still being very locally focused.”

“It’s interesting to think about telling more than just the story of the Dunham family 200 years ago, but also what the land looked like before they arrived, and what happened in that 200 years of history after they moved on,” she said. “Connecting people to this place across time is the goal.”