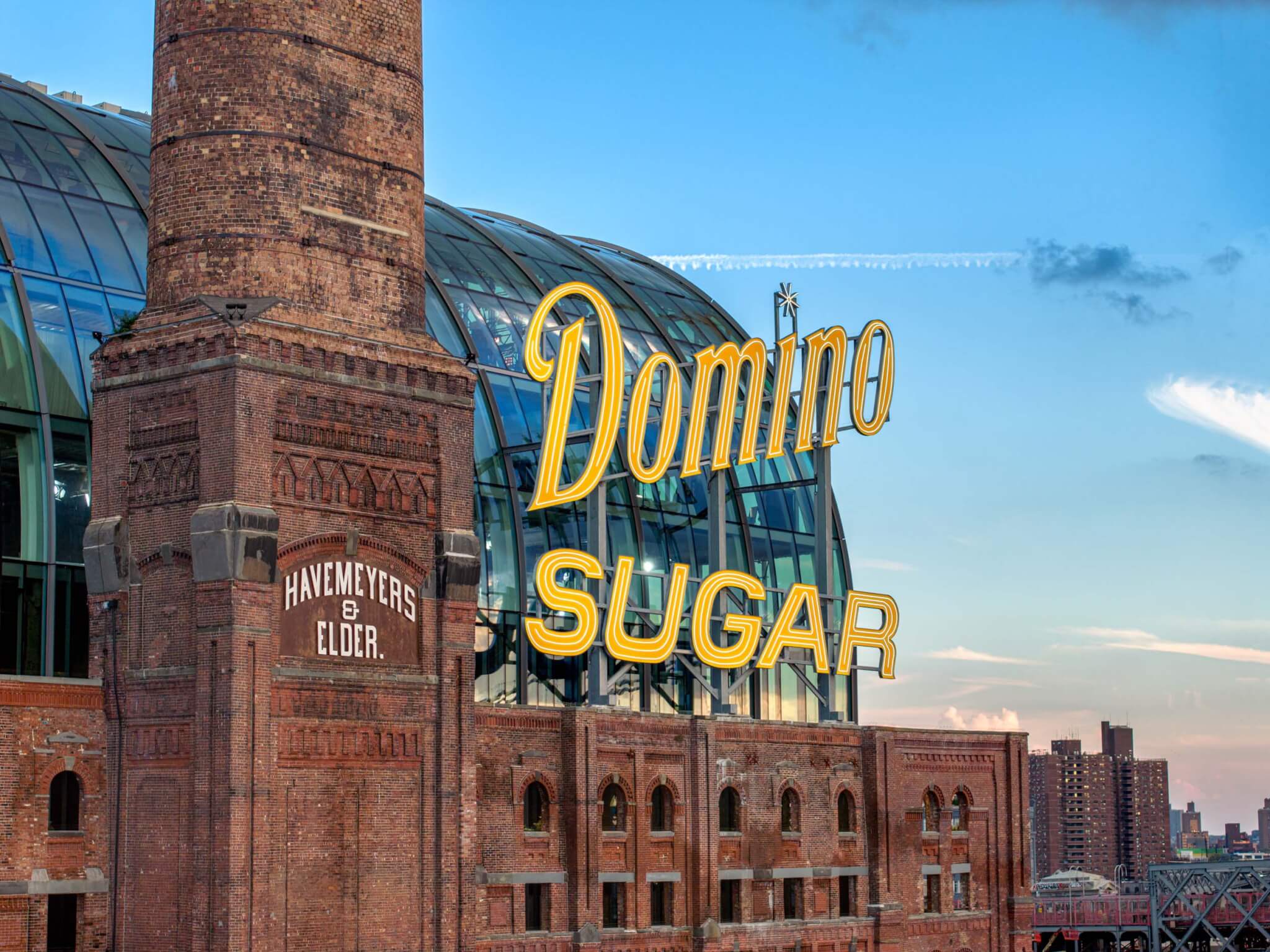

“This is the jewel in the crown,” said Vishaan Chakrabarti of Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU). He was talking about the office’s reimagination of the Refinery at Domino, which just finished construction as part of a wider redevelopment scheme that has transformed this run of the Brooklyn waterfront into a warren of glazed high-rises. Here, on the top floor of the PAU-designed building, some traces of history remain: This glass box with a barrel-vaulted ceiling rises three stories out of the brick shell left behind by a structure that originally housed the panning, filtering, and finishing operations for Domino Sugar. Putting a new building inside an old one is a clever approach to adaptive reuse for such a drastic change of program: from sugar processing to office work.

Ruchika Modi, the project architect, told me that the refinery building was, in fact, not a building at all. “In a building you would expect some relationship between the exterior and the interior. It was a bunch of cavernous spaces,” she remarked. “It was really just a giant piece of machinery cloaked in masonry.” This rationale led PAU to treat the brick facade like a sleeve, inserting a brand-new office building between the four masonry walls. A continuous vertical gap that ranges from 10 to 15 feet in depth separates the glass exterior of the offices from the refinery’s old brick, allowing light to reach the office spaces to be fitted out by future tenants. Open to the elements, the void is also filled with plantings, including 17 trees. When I visited, most of the nonarboreal greenery was in fact fabric and plastic replicas of plants, a stopgap measure taken, I assume, to encourage potential tenants to sign a lease. This gap is uninhabitable except on the ground floor, where PAU dropped the sills of the windows to grade level. The move was not without precedent: “We wanted the building to look like a historic building,” Modi said. “But this used to be a factory building; they didn’t care about how it looked. If they needed to poke a hole, they’d poke a hole. It wasn’t precious. We wanted to maintain that ethos.” Standing between the new building and the old shell is akin to being in a hall of mirrors, the expanse of glass reflecting both the inside of the brick shell and the buildings on the other side of it.

PAU hopes that the building’s ground-level porosity will encourage passersby to look in and, once food and beverage establishments open inside, entice them to buy. On the upper floors, where the gap becomes an uninhabitable void, the narrow distance between the glass and the brick has a vertiginous effect, providing only a slim wedge of views up and down. Arched openings in the brick—these were the inspiration for the glass box’s form—provide pleasant enough views onto the waterfront, its attendant park (designed by Field Operations and the first piece of the development to finish), and nearby residential towers, completed and under construction. Construction is moving apace, likely spurred by the controversial and now expired 421a tax abatement program, which exempts owners from paying property tax if their property value changed because they did construction on a multifamily residential building.

The pressure might be on to finish, and according to the master plan, the design of a monster tower next to the Domino is yet to be unveiled, but the development has been in the works for more than a decade. The refinery shut down in 2004, laying off 220 workers after being bought by the Community Preservation Corporation (CPC). In 2007, the Williamsburg waterfront was rezoned for mixed-use development, and the CPC proposed a plan for the site that turned out to be highly unpopular; it made few concessions to local residents, who feared they would be displaced by the development. (It’s hard not to feel that way after a factory that employed hundreds of people in your neighborhood shuts down.) And the corporation didn’t make good on a promise of 30 percent affordable units, either. Two Trees acquired the site from CPC in 2012, and the master plan by SHoP was unveiled the following year.

Domino has its own troubled history. Sugar was one of a few crops that fueled the slave trade in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was also catalyst for U.S. expansion into Puerto Rico, a process that saw 45 percent of that island’s arable land become reserved exclusively for sugar planting, leaving the territory dependent on imports for much of its food. The man who oversaw that process, Charles Herbert Allen, did so by creating the world’s largest sugar syndicate, the American Sugar Refining Company, now known as Domino Sugar. Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, the Domino refinery processed anywhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of all the sugar consumed in the United States, relying on labor from workers—many of whom were Black, many of whom were Puerto Rican—to turn its profits.

It should not be lost on anyone that The Refinery at Domino is indeed a new building camouflaged inside an old wrapper. It’s just another office tower by a for-profit developer, the 21st-century evolution of the rapacious expansion that has fueled the American economy for the last 300 years. The refinery might have nice amenities, and the park (another act of camouflage, by the way—it is, though it might not appear to be, private) might be pleasant to run through, but those benefits all pale in comparison to the $3 billion real estate portfolio this building is helping Two Trees consolidate. Across the development, 700 units of means-tested, income-dependent “affordable” housing, out of 2,800 total, are hardly a consolation price. The unfettered growth of enterprise, paid for in part by the displacement of working people, churns on, though here PAU’s architecture maybe makes it easier to accept. The trees craned in from above, the LED replica of the Domino Sugar sign, the barrel vault pushing out through the brick like a modern-day Crystal Palace—it’s all perfectly palatable cover for the fact that this crown jewel might be a blood diamond.

Marianela D’Aprile is a writer and the deputy editor of the New York Review of Architecture. She lives and works in New York City.