This summer will go down in New York City lore as when Hotel Pennsylvania met its maker.

Demolition of the McKim, Mead, and White–designed Beaux Arts tower from 1910 will unsanctimoniously come to a close soon. A few scant steal beams rise upward on the site where celebrities and politicians like Duke Ellington and Fidel Castro once rested. The edifice’s heralded ballroom was where the master propagandist Edward Louis Bernays gave a speech for merchants unveiling his grand plans for the 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair; arguably altering the course of American history. If only Hotel Pennsylvania’s walls could talk.

The edifice wasn’t a landmark, but there were protests to save it. In 2008, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission passed on granting Hotel Pennsylvania landmark status. Some hardcore preservationists wanted to see it remain because of its temporal connection to the original Penn Station; other more politically-inclined folks saw its demolition as endemic of the scorched-earth style development in New York that’s gone unchecked for too long.

Today, commuters exiting Penn Station have been given a never-before-seen vista by Vornado of the Empire State Building. But the view won’t last for too long. The gaping hole in the ground where Hotel Pennsylvania once stood will be filled in by PENN15, a Foster & Partners–designed 1,200-foot supertall backed by Vornado Realty Trust, who purchased Hotel Pennsylvania in late 1990s. There is no construction timeline in place for the 56-story tower, but upon completion, PENN15 will deliver 2.7 million square feet of office space at the heart of the 7.4 million square foot Penn District master plan in midtown.

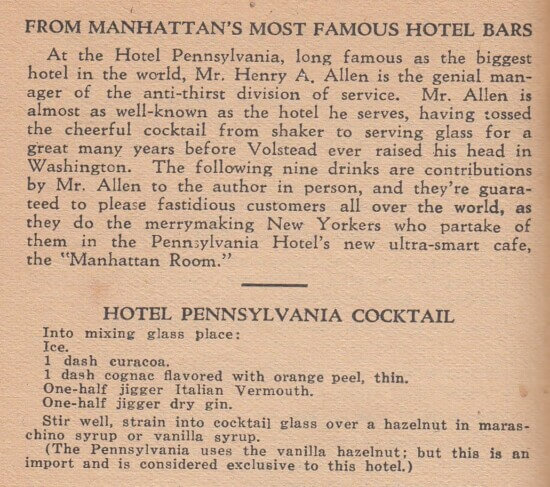

The building wasn’t beloved for its architecture per se. Despite its grandiose gas lanterns, Hotel Pennsylvania was a fairly economical building for its time that didn’t have nearly as many frills as its raison d’être Pennsylvania Station just across the street. Rather, many New Yorkers felt an attachment to it because of what happened inside its vast ballrooms, winding corridors, and 2,200 rooms.

Before there was Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel, there was Hotel Pennsylvania. Akin to Anderson’s 2014 scintillating rendition of hotel life, the edifice was such a riddle that Hotel Pennsylvania had its own newspaper in order to communicate its clock-like inner workings to guests, The Pennsylvania Register, a four-page leaflet that was distributed to every single bedroom on a daily basis starting in 1921, except on Sundays and holidays. The building was made internationally famous in 1940 when Glen Miller sang its phone number on the airwaves: Pennsylvania 6-5000, Oh oh oh!

If you live in New York long enough, watching buildings once thought of as permanent fixtures get demolished will happen more than once to echo Fran Lebowitz. This regenerative cycle, of solid melting into air in perpetuity, is paramount to what Marshall Berman said keeps the island-metropolis “modern”; or what Rem Koolhaas called Manhattanism.

These theories that have perhaps outlived their usefulness aside, there’s just something about Hotel Pennsylvania getting the wrecking ball that feels different.