“And where is the baby’s ticket?” the security guard asked, causing us to chuckle in unison along with those behind us. My wife and I were in the queue at the Giardini entrance to the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, themed The Laboratory of the Future, with our nine-month-old daughter, Roux, in tow. We had already folded our own passes back into our bags, stuffed somewhere between the diapers and mini cooler of formula milk, expecting to proceed through the gate. Then, to our surprise, a follow-up: “I’m not joking.” The guard proceeded to tell us that our baby, strapped to her mother’s hip, needed her own ticket. We excused ourselves and sauntered over to a small, green building across from Paradiso. A welcomed gust of conditioned air escaped the ticket window, giving us an extra boost of mental clarity. After two car rides, three flights, a boat, and a short walk to the ticket booth, our journey would face one more obstacle. But hey, we’re at the Venice Biennale, and Roux ended up getting in for free.

Like the security guard, the folks in the ticketing booth were also apologetic for the delay and reassured us with their disagreement with the policy. Yet, they simply must comply. With a scan of the baby’s passport, we were able to proceed into the Giardini. “That’s Italian administration for you,” commented Aaron Betsky, director of the 2008 Venice Architecture Biennale, on hearing about the delay. Even a certified Castello expert such as Betsky was not aware of the baby-ticket policy. This was, we discovered, par for the course: To experience the Venice Architecture Biennale with a baby is both a logistical hurdle and an undeniable lens through which to view the work itself.

We, Ryan Scavnicky and Kristen Mimms Scavnicky, two architecture professors, were on a research trip with a young baby who wasn’t yet sleeping through the night. We figured between the time zone change and wild scheduling it would be easier to bring the baby than leave her with the grandparents. But, unlike the 1987 blockbuster Three Men and a Baby, starring Tom Selleck as a thriving New York City architect with his two goofy roommates, we felt prepared to roll with the punches of new parenthood. After all, we had diligently researched top tips and must-have parent products for traveling overseas with a baby, but that abrupt halt at the gate of the Giardini was a bumpy start. Bumpy also describes the general ground condition in Venice, and it is the last word you want to hear when it comes to toting a baby around because uneven surfaces are obviously not stroller friendly. With the tight tourist crowds and charming cobblestone streets in mind, we abandoned our hybrid stroller/car seat upon arrival at the Cleveland Hopkins Airport and depended solely on a hip carrier that cantilevers the baby off your body, reducing pressure on your back and waist. This purchase would prove to be the MVP over the next six days. Not only did Roux’s sitting ledge enable easy feeding and napping during the day of sightseeing, but she also had a front-row seat from which to view the city.

After meandering for some time, we made it early enough to the U.S. Pavilion to grab a seat in the shade for the opening remarks for Everlasting Plastics, curated by Tizziana Baldenebro and Lauren Leving. Kristen’s memory immediately flashed back to her childhood when the sculptural columns of Little Tikes’s chunky yellow chairs by artist Lauren Yeager came into view. Would Roux play house with the same chunky kid chairs I once had? Would being present at this event set her on the trajectory to make-believe that the walls of her imaginary dream house snaked around those magical chairs, much like my mom had done 35 years prior? Snapping back to the event at hand, these wholesome thoughts were replaced by existential anxiety for the potential physical landscape of Roux’s future. Perhaps the chunky chairs and all other single-use plastics will smother the earth before she reaches her mother’s current age.

Proceeding through the pavilions of the assorted countries, we, the Mimms-Scavnicky crew, took in the creative works, attempting to bookmark each inspiring moment via memory maps, snapping iPhones photos as a backup. In search of work directly related to Kristen’s research agenda, we happened upon emotive, storytelling ceramics by Toni Griffin of Urban American City in a piece called Land Narratives—Fantastic Futures. The vessels mimicked the sound waves of eight Chicagoans’ voices as they recounted their joy of Black space. Kristen wondered what hers might look like if she spoke about the thrill of seeing Griffin’s work in the historically white exhibition spaces. Glancing over at baby Roux bouncing around other displays, something clicked. Meeting Griffin made her heart dance with relief; we had good reason to fly across the world with our infant child.

Neither of us imagined missing the opening talk at the Dutch Pavilion to change a diaper on a bench out front. Yet while Jan Jongert of Superuse, a former professor of Ryan’s during a study at L’Ecole Speciale d’Architecture in Paris, gave the opening talk for Building Ecosystems, he was outside slathering Vaseline on our little one’s tiny backside. (There were no changing tables in the men’s restrooms, and Kristen was busy.) Anyone who has been to a vernissage at the Venice Biennale knows you can’t attend everything, there is too much happening all at the same time, but you really can’t attend everything if you are bringing your baby.

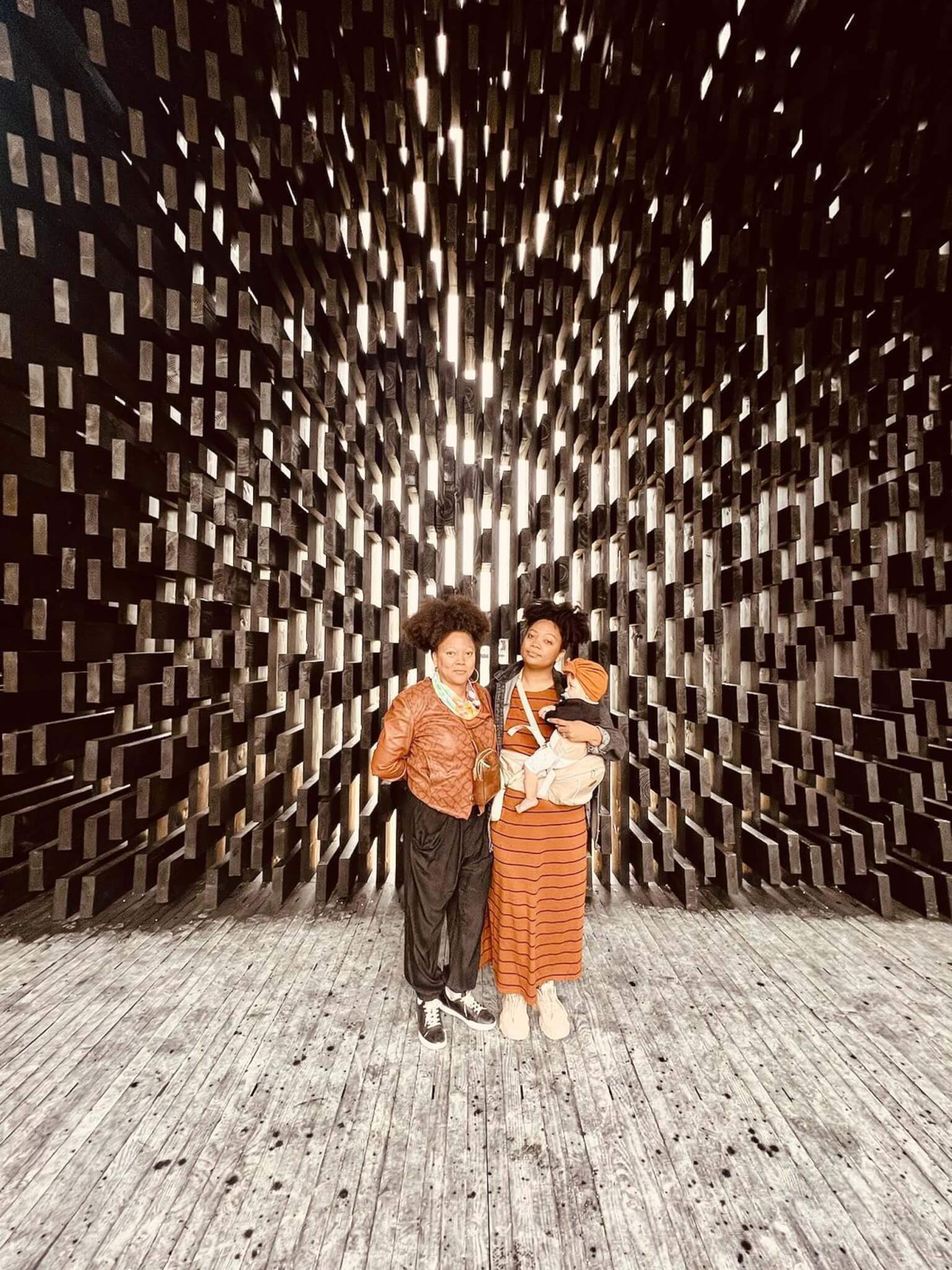

On the second day of the press opening, we visited the Arsenale’s exhibitions. After a long, sweaty walk from the Giardini, the sky blessed us with a misty rain. Near an entrance to the indoor exhibition, we spotted a dark, pointy structure and beelined to its portal. Upon entering, we appreciated the lattice texture of individually stained studs that made the pyramid whole, a clever agglomeration by Adjaye Associates. Back stateside and having heard of the allegations against David Adjaye which would emerge after our trip, we couldn’t help but lament the sad truth that there will still be workplace hurdles for Roux when she enters it as a Black woman. We are architecture educators, so it is our responsibility to empower our students to “change the very structure of architecture,” as Kate Wagner elegantly put it.

Upon entering the dim, winding path of the Arsenale’s interior, a different mood enveloped us. The space felt much more intense than that of the Giardini. There was a darkness that helped to dramatize the works on view and simultaneously soothed the baby to sleep. It’s a great place to take a break from the heat and let your little one find respite. In particular, The Great Endeavour by Liam Young which featured costumes by Ane Crabtree, fascinated us as a tool for imagining a better future. Especially while toting around a little tot, we have no choice but to be hopeful.

While there was an abundance of cicchetti and spritz in our bellies, there was an undeniable lack of changing tables where the lion’s share of the Biennale actually takes place: in Venice’s picturesque trattorias. Even so, restaurant staff were always friendly and willing to help. One staff member carried a chair into the bathroom for us to use, while others had premium highchairs. All offered friendly smiles. One waiter walked us across the palazzo and around the corner into another building where they had some storage so we could have a quiet, private place to change a diaper. It’s quite normal not to have contemporary infrastructure like changing tables in the older cities of the world; but while ad-hoc solutions work for our adventurous spirits, that might not do for everyone else.

Still, the lack of baby-friendly infrastructure is indicative of the way the Biennale itself is set up. Beyond the inconvenience, it can be an interference for the daily lives of locals who use the Giardini as an actual park before it’s closed off into a spectacle for pomp and circumstance. This was the theme of Roux’s favorite installation, the guerilla exhibition Open Giardini! by Davide Tommaso Ferrando and Daniel Tudor Munteanu, which cataloged the various architectural insertions that closed off the Giardini itself to the public. During the Biennale, objects like red clown noses, red carpet, and red paint were used to create guerilla openings into the Giardini to help outsiders “jump the fence.” Baby Roux also liked the Austrian Pavilion by architect Hermann Czech and the collective AKT, where it was proposed to create a new entirely free public entrance at the back of the building which borders the Giardini that was ultimately vetoed by the Biennale and city authorities “for security reasons.”

The general attitude on display across the Laboratory of the Future suggests that the field as a whole believes that access for everyone—the wheelchair-bound, the elderly, and, yes, babies—is enmeshed with the narrative of change surrounding Africa and the African Diaspora. We think making our international exhibitions more accessible would be a good place to start.

Kristen Mimms Scavnicky is an assistant professor at Kent State University College of Architecture and Environmental Design. She is an artist, designer, and educator whose research and teaching agenda focus on how art and architecture can and should engage with the world as activists.

Ryan Scavnicky is an assistant professor of practice at Marywood University School of Architecture. He is the founder of Extra Office, a design practice engaging media to uncover new channels for architectural content.