Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: Breaking All the Rules runs through January 20, 2020, at the Architecture and Design Center of the Palm Springs Art Museum. Organized by Brooke Hodge, the museum’s director of architecture and design, it is not a traditional architecture, graphic design, or art exhibition, but straddles all these lines, hence the title (similar to that of a small monograph on Ms. Stauffacher Solomon published by Hall of Femmes). If you are in Palm Springs, it’s an exhibition worth checking out.

The Architecture and Design Center occupies E. Stewart Williams’s Santa Fe Bank Building, one of those great Palm Springs banks that took inspiration from a world-famous architect; in this case, Mies van der Rohe. The “universal space” holds several pieces from Stauffacher Solomon’s diverse career, which is hard to pin down. Although visually powerful, the narrative can be a little difficult to piece together.

Stauffacher Solomon is best known for her graphic design at the Sea Ranch on the Northern California coast. She has been credited with the invention of “Supergraphics” as a result of her work there, and she got almost as much press coverage as the architects for her simple, bold moves. But that work has been largely excluded from this show, as it focuses on selections from the rest of Solomon’s career.

It is important to understand her story. “Bobbie” grew up in San Francisco and lost her first husband to a brain tumor at a young age. In order to make a living and raise their daughter, she moved to Basel, Switzerland, to study with Armin Hofmann. This sets the stage for Stauffacher Solomon’s subsequent work in graphic design, landscape architecture, and fine art. She is always moving between the rigor and discipline of Swiss Modernism and the radical spring of groovy California. She reveals some of this in the videos on display, which provide a context for appreciating the drawings, paintings, and new supergraphic—and her own mischievous delight.

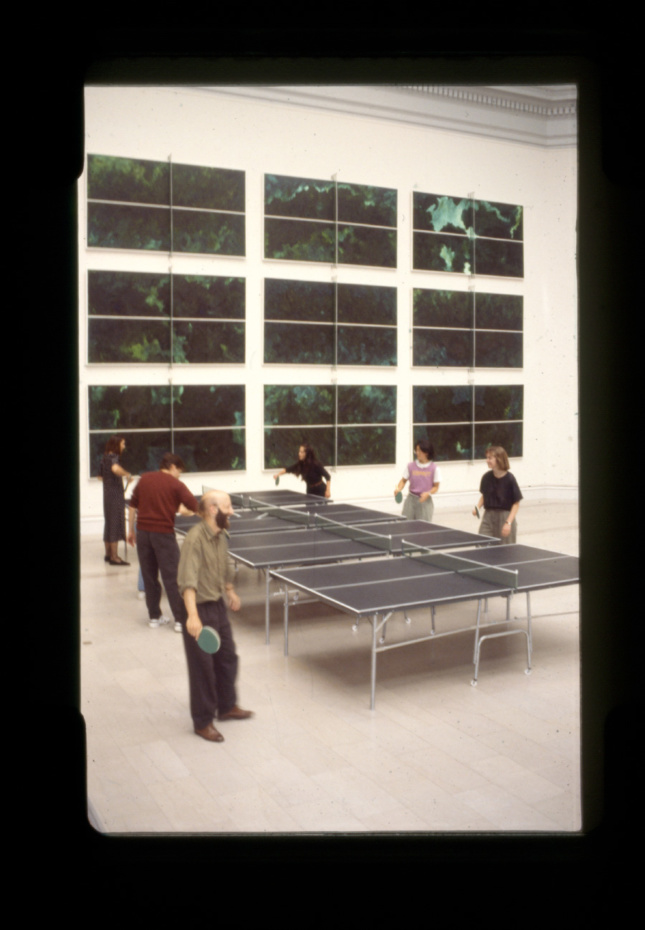

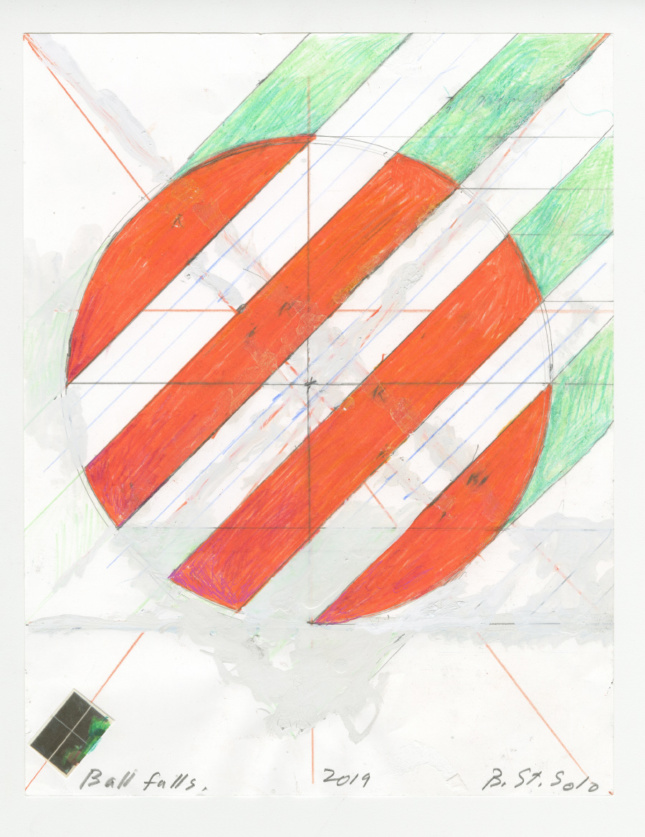

A group of eight of Stauffacher Solomon’s ping-pong-themed paintings takes up the most space in the museum. Immediately, the visitor is intrigued by the sound of ping-pong being played somewhere just out of sight. The paintings, the exact size of ping-pong tables, hung horizontally when originally shown in 1990 at the San Francisco Museum of Art. In Palm Springs, they are displayed vertically, which is interesting given the relatively low ceiling height. Each canvas depicts a lushly illustrated green Californian landscape complete with white lines and nets. In addition to the sound of ping-pong balls bouncing, there are several actual ping-pong tables with paddles and balls. The paddles and balls were removed in San Francisco, but here, all are encouraged to play. An accompanying selection of drawings shows these rectangular green spaces in the urban landscape.

“To ping is to sing.”

“To pong is to go wrong.”

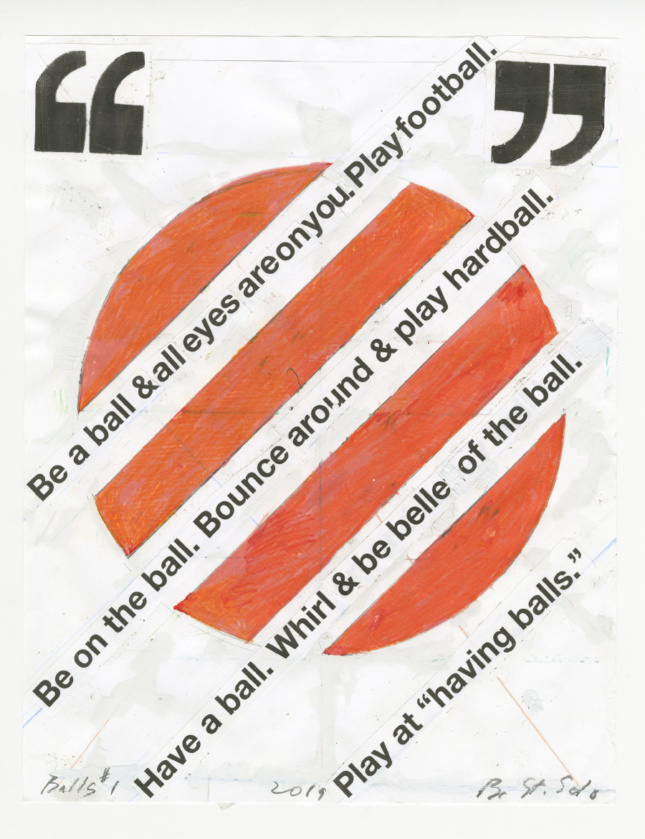

Commissioned for this show, Solomon designed a new accompanying supergraphic overlooking the Ping-Pong tables with those few words. A supersized red ball appears to hurl through space.

Stauffacher Solomon’s supergraphics at Sea Ranch were rooted in the severity of her mentor Hoffman’s training but also showed her rebellious side, with bold use of color and humor (find the suggestive figures in the Sea Ranch’s Moonraker Pool Center next time you visit). Her work there, painted in a few days, covered an unfinished building that had gone over budget. Since her contributions to supergraphics and Sea Ranch are well known in the design worlds, this smaller show explores less familiar aspects of her career.

Following the success of her interpretation of Swiss Modern graphics, Stauffacher Solomon returned to school at the University of California, Berkeley, and worked with the overlaps of architecture and landscape architecture. She ended up painting all kinds of green rectangles, including the series that resembled ping-pong tables. Her master’s thesis was entitled “Notes on the Common Ground between Architecture and Landscape Architecture.” Her ideas later coalesced in a book from Rizzoli, Green Architecture and the Agrarian Garden. This phase depicts her evolution from almost pure graphics to landscape depicted graphically.

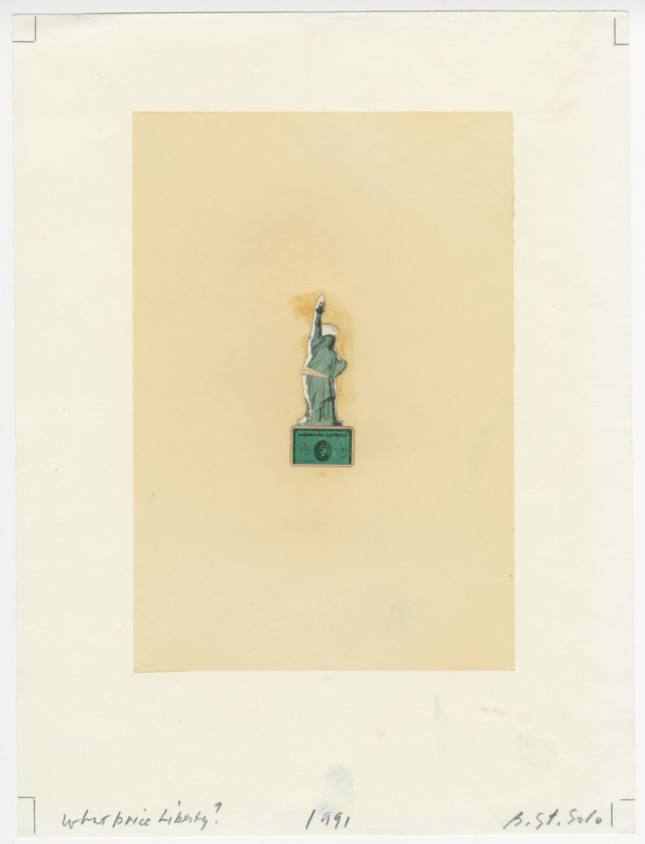

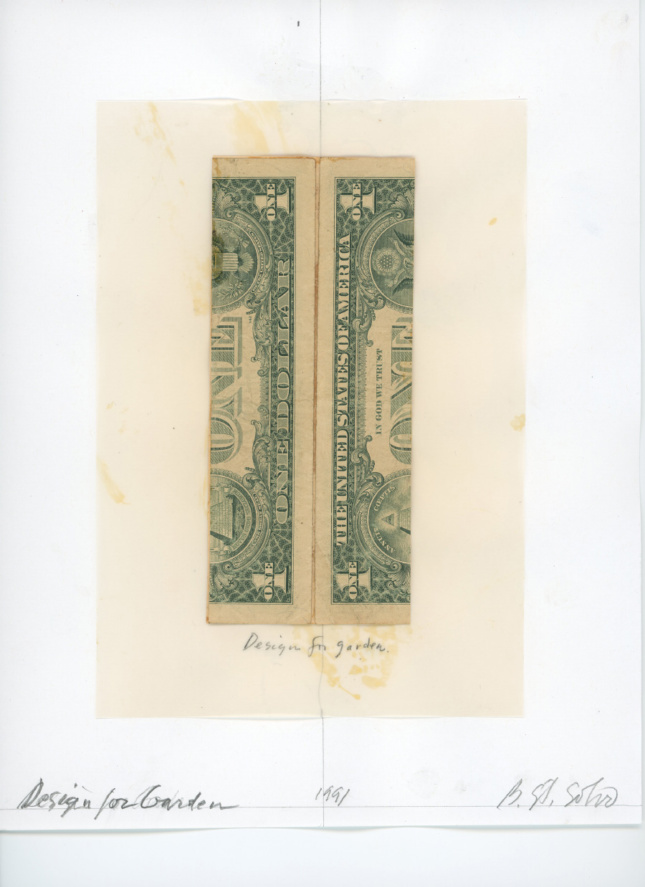

Yet her first book from Rizzoli, and the art that accompanied this period, was still rooted in the discipline of graphic design. Her journey moves on to a series of artworks that she gathered in a second book from Rizzoli, Good Mourning California, which embraces her home state and its many quirks yet foretells its possible demise. Some of the drawings of women seem influenced by German-American artist Richard Linder. The pieces are rougher, wilder, even angry.

Without watching the two videos in the exhibition, it might be difficult for the uninitiated visitor (i.e. not a design aficionado) to make sense of Breaking all the Rules. Listening to Stauffacher Solomon describe her life and work on the videos provides the necessary frame of reference. She describes her early art studies, working as a dancer at San Francisco’s Copacabana nightclub while still a teenager, meeting her future husband at 17, befriending leading bohemians, rebuilding her life as a very young widow and mother, being disciplined by Swiss Modernism, applying that discipline to California in the 1960s, becoming the darling graphic designer of the city’s architecture scene (no surprise—trying to rein in the future chaos of postmodernism), and trying to synthesize thoughts on architecture, landscape architecture, design, the environment, and everything else. It will take a different show (and larger venue) to tell Bobbie Stauffacher Solomon’s design and personal story more completely, but this is splendid first look. Be sure and play some ping-pong.