Last month, French architect, historian, professor, and curator Jean-Louis Cohen died suddenly. He was 74. News of his death rippled through the architecture community, with colleagues, former students, and admirers sharing tributes and memories on social media. Cohen was unfailingly thorough, a generous mentor, and larger than life. He leaves behind a legacy of progressive politics in architecture and a global network of peers.

To pay tribute to Cohen’s life, AN has collected remembrances from friends, colleagues, and former students. He is missed.

Vladimir Belogolovsky, author, historian

With so many projects in the making and so many plans cut short, Jean-Louis Cohen left my life as suddenly as he entered it. We were introduced by Phyllis Lambert at the opening of Lost Vanguard: Soviet Modernist Architecture, 1922–32 at MoMA in 2008; he was that show’s guest curator. Upon hearing my name, he swiftly switched from English to my native Russian, which he learned in high school and spoke fluently. In our follow-up meeting that year at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, he told me, “I come from a Parisian Jewish family in which there were two religions: science and revolution.”

Jean-Louis discovered another religion: architecture. He became fascinated by it as a teenager through his close friendships with Paul Chemetov and Anatole Kopp. His enthusiasm for Soviet architecture prompted me to introduce him to my friend, Soviet architect Felix Novikov, whose work Jean-Louis praised in his 2011 book The Future of Architecture Since 1889. We flew together to Rochester to meet Novikov in 2021. They were absolutely happy together speaking eagerly about countless acquaintances and projects, and plans, of course. Novikov died last year at the age of 95, and Jean-Louis died this year. Both lived as much in the past as in the future.

Emily Bills, professor, The New School

With Jean-Louis, architecture was always fun. I was his graduate assistant at the NYU Institute of Fine Arts when he offered his first Los Angeles seminar. Jean-Louis determined the class’s pièce de resistance should be a fully funded trip out West. He declared our journey a salute to Reyner Banham’s BBC documentary Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles and somehow attracted the attention of a Los Angeles Times reporter, who followed us around for a week as we traveled from Gamble to Eames Houses, cruised the PCH, and took photos of dingbat apartments.

Jean-Louis rented himself a sports car, and then tasked me and the other Californian in the class (i.e. the only people in a group of New Yorkers fit to drive) with piloting two minivans. He drove like an Angeleno, crossing three lanes of traffic and exiting without warning. This was before GPS, and we had to keep up or risk derailing our packed schedule. I think the near-death freeway experiences, as much as the architecture, bonded us as a group.

Jean-Louis pulled all of his connections for us. We gained an invitation to Frank Gehry’s house, toured the Disney Concert Hall construction site, and chatted with the original owner of a Case Study House, who served us lemonade poolside. I later moved to Los Angeles, guided, no doubt, by his appreciation of the city as a place of experimentation and possibility.

Jean-Louis helped his students see architectural history as an interdisciplinary practice, modeling for us scholarship that makes connections across geographies and cultures. In this, he also mentored generations of teachers. Whenever I take a group of students on an architecture tour, I think of Jean-Louis, gesturing wildly out his window at some building or landscape he couldn’t wait to share, our enthusiastic leader.

Anna Bokov, PhD, architect and architectural historian

Jean-Louis Cohen’s unexpected passing is a devastating and unfathomable loss for the architectural community and so many of us who knew him and learned from his brilliance.

I feel fortunate to have been one of the PhD students who had the privilege to learn from him. He always made you feel like your work mattered and graciously made time despite his full schedule. He would always find the right words, offer precise constructive criticism, and point you in the right direction. His sage advice has and will continue to inspire my professional work.

As both a world expert and a local insider in so many diverse cultural contexts, Jean-Louis had an uncanny gift for connecting people from different worlds and different cultures (without ever being on social media). He cultivated a vast social universe around him, built upon a love of architecture and humanity.

He will be remembered as a preeminent intellectual, a prolific author (who last year, alone, published nine books), and an undisputed authority on every topic he focused on and in every format he worked in.

Jean-Louis Cohen was a bright star among us who was taken from this life unexpectedly. His luminous legacy will, indeed, continue to shine, teach, and live on.

Giovanna Borasi, director and chief curator, Canadian Centre for Architecture

“I like to share knowledge and I do not keep it for myself, for my books. I’m curious about other people,” Jean-Louis Cohen once said.

Jean-Louis was a uniquely gifted intellectual, critic, historian, and institution builder, capable of understanding diverse cultures and situations wisely and compassionately. He was curious, engaged, political, funny, humble, generous, and, most impressively, able to do many things at the same time without ever seeming busy. Each of these qualities, and undoubtedly more yet to be discovered by future scholars, are evident in his archive, which he donated to the CCA in 2019.

Jean-Louis was integral to the CCA over many years and in several capacities: as curator, as chair of the Collection, Research, and Programs Committee, and, since 1998, as a board member. Our relationship began in the early 1990s, when he first discovered the CCA Collection and was impressed by its distinctly transnational holdings. Jean-Louis felt that working with the entire CCA team was an exceptional experience, and the feeling was mutual.

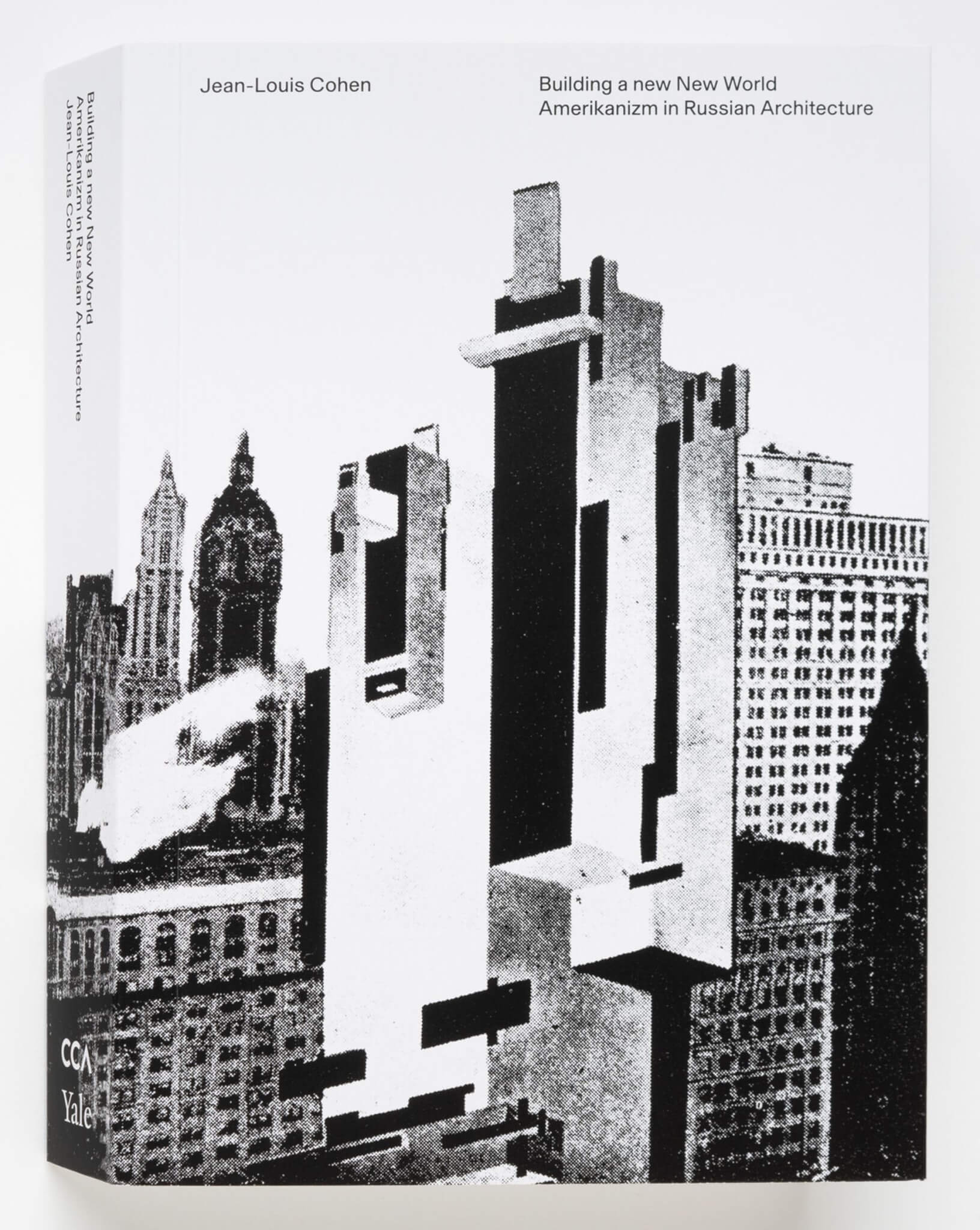

I had the privilege of working closely with Jean-Louis on the preparation of two of his shows at CCA: Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War (2011) and Building a new New World: Amerikanizm in Russian Architecture (2019–20). I have learned a great deal by observing his curatorial approach and research methodology. He spoke many languages very well (seven at my count), and this offered him the opportunity to conduct research into primary sources all by himself with no mediation.

The first step of planning a show with him was the decision as to how many new archives he needed to visit and explore. Each show was a research project in itself, and the first-hand experience of the drawings, notes, and thoughts of different architects made him a medium in which parallel histories could be connected. He was a strong believer in databases and insisted on putting in the data himself, so that all that knowledge he had acquired could be transferred and made accessible and sharable. Surely there are so many archives he still wanted to see, to research, and to engage with.

We are grateful and honored to preserve his archive, which gives access to his personal papers, manuscripts, ideas, trials and errors, and generously invites future researchers to build on his great legacy.

I, like so many others who knew him, will miss him deeply.

Maristella Casciato, senior curator, head of architectural collections, Getty Institute

In a recent interview Cohen said of himself: “I am a multitasking character and I work on many parallel projects, which are inscribed in different temporalities.”

At the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, we say adieu to Jean-Louis Cohen. He belonged to the first cohort of scholars who inaugurated the Scholar Program in the fall of 1985 under the theme of “Aesthetic Experience and Affinities among the Arts.” Cohen never stopped experimenting with that subject. In 2018, he donated to the GRI a relevant corpus of the papers of the architect, historian, and journalist Roger Ginsburger; in his archives exists documentation related to two important books whose young authors he mentored: Richard Neutra’s Wie Baut Amerika (1927) and Erich Mendelsohn’s Amerika (1928), both of which hold unique resonances to GRI Special Collections.

Following the acquisition of Frank Gehry’s Papers, 1954–1988, by the GRI, most recently Cohen began a gargantuan project of producing the catalogue raisonné of Gehry’s sketches; he was in the midst of researching and writing the second and third volumes of Frank Gehry: Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings, whose first volume debuted in 2020.

Jean-Louis, your warm presence and gentle smile will be missed—in the GRI Special Collections Reading Room, at Getty, and beyond.

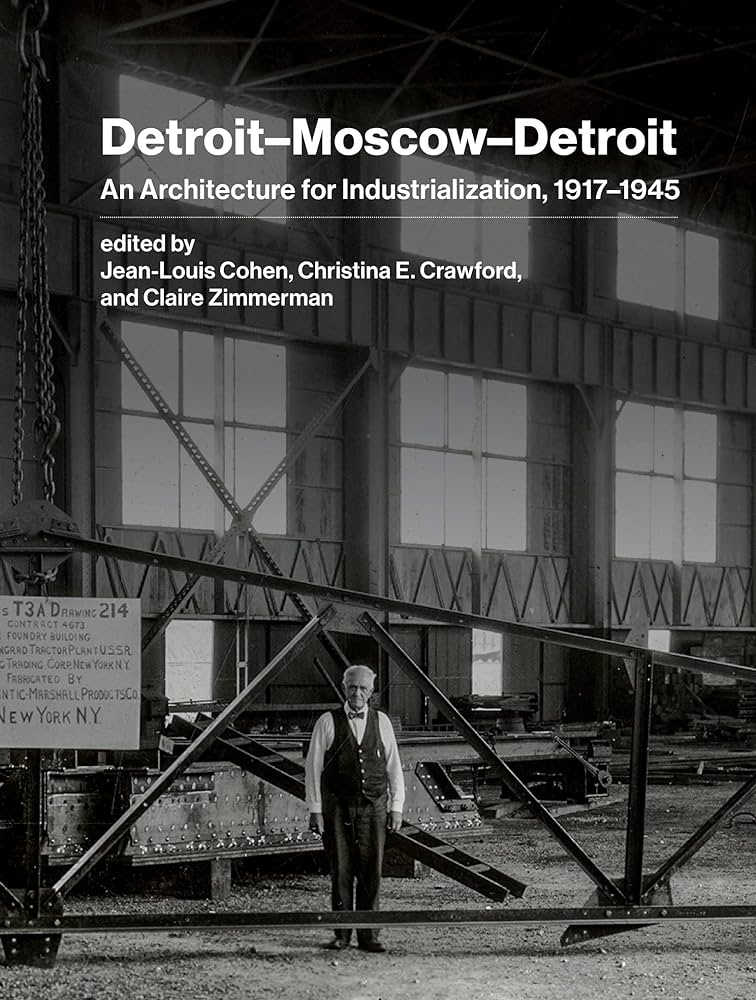

Christina E. Crawford, professor, Emory University

The architectural history world is small, and the number of senior scholars with expertise on Soviet architecture can be counted on one hand. So, when I left architectural practice to pursue doctoral research on early Soviet city–building, I knew that I couldn’t get very far without Jean-Louis Cohen. Our first meeting was in a café, right before he was scheduled to give a guest lecture. He had read my prospectus on the train and, without much preamble, launched into how to demystify the seemingly impenetrable mechanisms by which Soviet projects in the 1920s were designed and constructed. “Follow the money,” he advised. He was right, of course.

This unremarkable story nonetheless exemplifies the easy generosity with which Jean-Louis—celebrated scholar, unparalleled intellect—moved in the typically hierarchical world of academia. He responded immediately; made time to meet; read students’ research with interest, curiosity, and excitement; and dispensed pragmatic advice that set so many on the right path. Jean-Louis showed up for people. His mentees from multiple generations are grieving the loss of a mentor who had become, in subsequent years, an ardent supporter and true friend. I regret the loss of the books that Jean-Louis, who was productive beyond all reasonable measure, will not write. But I deeply mourn him, the center of an architectural universe.

Edward Dimendberg, professor of humanities, UC Irvine

I first met Jean-Louis in New York, though we more often saw each other over dinner in Los Angeles, where in recent years he was a frequent visitor as he worked on Frank Gehry’s catalogue raisonné. Even before this project, he admired the city and its architecture and regarded Los Angeles and Southern California fondly and without the slightest hint of condescension.

I once invited him over for dinner. After he arrived, he looked around and pronounced our house beautiful. Only afterward did my wife, Lynne Berman, and I realize both his generosity toward the mishmash we inhabit and the unlikelihood of passing muster with such a distinguished guest. Lynne appreciated his kindness and ability to engage with people who were not academics or architects and the warmth and curiosity he brought to encounters with those who could not help him. Although I was never his student, he aided me over the years and unfailingly answered emails, supplying help and recondite information. When I took the participants of a conference I organized to lunch and warily invited them for a glass of wine, I, the teetotaler, watched with amazement as Jean-Louis downed a large glass of Merlot with nary an effect and soon thereafter mesmerized the audience with a brilliant lecture.

In the weeks after his death, I checked The New York Times daily for the obituary I thought would appear. When none was forthcoming, I wrote to the paper and received a polite reply thanking me for supplying information and stating that it would not be possible to publish anything about his life. At a time when the deaths of so many flashes in the pan are routinely commemorated, I take the decision not to recognize the many accomplishments of Jean-Louis as a scholar, curator, teacher, and public intellectual as confirmation of just how low the status of architectural scholarship has fallen in collective life. Apart from providing quotable comments on exhibitions, famous architects, and preservation issues, today architecture scholars are largely invisible in the mainstream media and have little traction beyond academic and professional circles. The realization that dedicated stewards and analysts of the built environment have scant presence in contemporary American society compounds the loss of an inspiring and beloved friend, colleague, and mentor.

Kurt W. Forster, professor, Yale University

One can only guess what may have made Jean-Louis Cohen to be the most popular Frenchman in architecture (outside of France). What was it like to be held in high esteem in his native France, lecturing at the Collège de France, and yet so deeply interconnected with American interests and universities that for some areas of research in modern architecture it was his name alone that came to mind first and last? I remember an evening at Jean Louis’s apartment at NYU, when the shelves were literally groaning under the weight of his books. I also remember Jean-Louis’s powerful learning and ability to communicate, translate, advise, and propel along so many attempts in different universities that never quite repaid his generosity. It was an exciting moment seeing a student hit her stride after discussion with this unique mentor whose knowledge, sharpness, and sheer intelligence had greatly helped finding the right direction and mastering what it took to assemble a larger picture.

Nothing if not thorough, Jean-Louis was the ideal editor of the catalogue raisonné of Frank Gehry’s drawings, a project now somewhat stranded but hopefully to be recovered. Full of energy and wit, Jean-Louis had a reputation for a kind of ironic yet serious, playful yet fully informed in all he said and wrote. To say we miss him is too bland a statement, for we know there is no one around of comparable caliber, erudition, and joie de vivre. His work has drawn many furrows across historiography. He will outlive them as a simply unforgettable colleague and friend.

Reto Geiser, associate professor, Rice University School of Architecture; founding partner, MG&Co.

The architecture world has lost one of its most influential and prolific voices. Jean-Louis Cohen was an exceptional scholar, a sharp, encyclopedic mind, an impressive polyglot, a tireless advocate of archival research, a champion of architecture culture across continents and political systems, but, first and foremost, he was an architect at heart. The architectural exhibition, the productive intersection of research, teaching, and design, was consequently at the core of his work. Always juggling multiple exhibition projects at the time, he understood them as a parallel practice to his historical research, an outlet to reunite the architect and the historian in him.

I was fortunate to have been introduced to Jean-Louis’s world when MG&Co. joined the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s team to design the exhibition Building a New New World: Amerikanizm in Russian Architecture in 2019. Over the course of an intense and fast-paced year, we had the opportunity to dive deeply into Jean-Louis’s universe, a massive body of research he had built since the mid-1980s that highlighted a territory largely ignored thus far.

Jean-Louis was a gifted storyteller, which everyone working with him could experience. Our collective work sessions in Montreal, Houston, and over Zoom were a fluid combination of research seminar, library excursion, desk-crit, and, at times, lecture class. Exhibitions allowed him to construct narratives, and to combine historical research with criticism by means of effective montaging and by sequencing a wealth of artifacts.

Due to political challenges, Building a New New World had to be realized without access to original drawings and other loans from the largest repositories of Russian architecture. Bridging the east-west divides as he has done many times before, he resorted to film projections, personal narratives, and hundreds of books to tell his story as a historian. As in his other CCA exhibitions (Scenes of the World to Come, 1995; Architecture in Uniform, 2011), printed materials could constitute an entire exhibition by themselves, at times blurring the boundaries between exhibition and book. The latter was an integral, and maybe the most lasting part of any of Jean-Louis’s exhibition projects. They are, without exception, reference works that form the foundation for other scholars to build on.

This fall, Jean-Louis was slated to share insights on his latest exhibition project, Constructed Geographies: Paulo Mendes da Rocha, at the Rice School of Architecture. His intellectual rigor and generosity will be sorely missed, both here at Rice and in many other parts of the world that were touched by his incredible scholarship and humanity.

Alexandra Lange, architecture and design critic

The death of Jean-Louis Cohen has been a shock and a deep sadness. I had not seen him in person since the beginning of the pandemic, but it was one of the delights of adulthood that someone so smart, so connected, and, as a 25-year-old master’s student, so intimidating, could eventually morph from a teacher into a mentor into a friend.

I and several of my classmates in my IFA cohort are small women; when we first started at the Institute, I imagined us as ducklings following behind Jean-Louis. The dramatic West Coast version of this dynamic was captured in a Los Angeles Times article about a field trip he took us on to Los Angeles, perhaps his third beloved city after Paris and Casablanca. On that trip, our buttoned up, urbane advisor revealed himself to have a California persona—open collar, sportscar—and the rest of us, packed into minivans, could only rush across multiple lanes of traffic to catch up as we zig-zagged up and down the coast from Eames to Wright to Schindler to Gehry. I had never been to L.A. before and I still remember standing in the mirrored bathroom of John Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein house (the original Cocaine Décor) and thinking, Where am I? Where has this been my whole life? I hadn’t even known this kind of architecture existed, and it took a middle-aged Frenchman to show it to me. Jean-Louis didn’t want us to follow—he wanted us to catch up and, thanks to his tutelage, we eventually did.

When I began the MA program at the IFA, I had already been working as a journalist for four years. My plan was to get a PhD and then use that knowledge to support my work as an architecture critic. I didn’t realize then how unusual it was within academia, and especially during that era of the Institute, to encourage public scholarship. But Jean-Louis enthusiastically supported the notion of writing for mainstream media, and demonstrated, through his own writing, curation, friendships, and choice of topics, that engaging with the broadest possible public could be the core of the intellectual project.

His own work often took a topic that had been covered a million times—postwar architecture, Le Corbusier, Frank Gehry—and demonstrated that there were plenty of new things to say if you (he) looked at it from a different angle. Even though he spoke more languages, knew more cities, and had already published more work than most of his advisees ever would, he took our interests and ideas seriously, asking questions, asking us to be more provocative, and never herding us back toward some imagined safe architecture history. A radical proposal didn’t necessarily mean going to the ends of the earth but deep into the archives, interrogating the dominant perspective, politics, or value systems. My dissertation, which he enthusiastically supported, was on the surface about postwar corporate architecture, the most heroic and bureaucratic of topics, but ended up launching my ongoing research interest in collaboration and personal networks. Classmates wrote about sculpture, vernacular architecture, technology; there was never one dominant period, geography, style, or discipline for the dissertations his students wrote. He didn’t care about that kind of limit, or reputation management, or reflection, and he empowered all of us to ignore those terms as well.

Sylvia Lavin, professor, Princeton University

Jean-Louis wrote on a remarkable range of topics, evidence of his unfathomable erudition. His breathtaking knowledge, which he wore lightly, reflected a life-long commitment to the possibility that there was always more to learn, and often from unexpected sources. This made him a generous teacher, a natural collaborator and a deft institutional strategist but it also reflected his theory of architecture. Acutely conscious of the number of forces, people, questions, and values that shape the culture of architecture and its buildings, every object in one of his many field-changing exhibitions and every footnote in one of his seminal publications, was never the end of the story but always a door into possible futures. Like many, I can map my life according to encounters with Jean-Louis—archives in Lyons, dinners in LA and meetings, debates and joy in Montreal. The world is smaller without him.

This text was previously published by the CCA on August 11.

Mary McLeod, professor, Columbia University

It seems impossible to believe that someone so brilliant, so energetic, so productive and so full of life has died. Like so many others, I’m deeply grateful for all that Jean-Louis gave to architecture history, and how he repeatedly contested conventional historical categories, whether national boundaries, as in his studies of Americanism and of French-German exchanges, or traditional periodization, as in his revelatory exhibition Architecture in Uniform and in his lectures at the Collège de France.

His range was immense, extending across several continents; few, if any, of my generation knew as much about 20th-century architecture and urban planning, or had such an astonishing grasp of languages: he was fluent in at least five, and had a working knowledge of four or five more. Jean-Louis was also a remarkable leader, and an adroit politician, organizer, and activist. He knew how to make things happen, and was responsible for countless exhibitions and conferences, as well as leading important preservation campaigns. He enjoyed and valued collaborations, and the results were always productive, often exceptional.

Finally, I would like to mention his remarkable gift for friendship. His students all speak of his loyalty, his generosity, his endless support, as well as the festive parties that he hosted at his apartment at the end of every semester.

I was fortunate to meet him while we were both still in our 20s (before either of us had begun writing our dissertations). I still remember our first meeting: a meal together at a little Russian café in Paris run by émigrés. So many wonderful meals followed—he was a marvelous cook—as did so many special gifts. Last week, when I opened my refrigerator at my little country house, I found some remnants from his last visit—a bottle of French dessert wine, a piece of aged Gouda (which he’d always bring back from Rotterdam after spending time with his daughter Vera), and most precious of all, a bottle of peach jam, which he had made at his beloved family home in Ardèche.

Thank you, dear Jean-Louis.

Jack Murphy, executive editor, The Architect’s Newspaper

Though I never met Jean-Louis Cohen in person, I am shaped by his work through his publications, exhibitions, and students who are now leading professors and critics themselves. I saw him lecture in person exactly once, with his trademark lean and podium grip, as if he might hoist high the lectern and toss it across the room to prove his point. The night’s topic was a new release about Manfredo Tafuri; of course, Cohen had interacted with him in the 1970s. Who didn’t he know?

Earlier in life, I thought I had a grip on Le Corbusier’s Towards an Architecture, an enigmatic but canonical book that turns 100 this year—that is, until I read Cohen’s introduction to a new translation. His essay picks apart the author’s fabrications, laying bare the tactics deployed by Le Corbusier to create an ambitious but disjointed collection of declarations, mechanical equipment, (manipulated!) photographs, and early projects.

I spoke with Cohen on the phone when reporting about the Vkhutemas exhibition at The Cooper Union earlier this year. He was direct in his dismissal of the attempt to delay the show. Later on, I timidly floated the idea of a meeting, but he was already away for the summer and wouldn’t be back until early September. “Lunch then is a happy perspective,” came the fast reply. There won’t be a shared meal, but I’ll be working through his lifetime of scholarship for many years. The world still has much to learn from JLC.

Guy Nordenson, structural engineer and professor, Princeton University

Jean-Louis Cohen was exacting in every moment. My last evening with him was in Amsterdam when we somehow got tickets to the Vermeer show, last entrance, and were in the end alone in the galleries to circulate. I have photographs of him leaning into each painting then walking slowly, hands behind his back, forehead parting the way to the next room. Others have written eloquently of his extraordinary and relentless productivity, broad and deep. We worked on a few topics together, but mostly we talked. He had a special place for engineering which he said came from his early days in Jean Prouvé’s class at, I believe, the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers. Together with my brother in structures, Marc Mimram, we always felt understood and supported in our work, teaching, and writings. We had many projects ahead of us. We forget too easily how close to us death always is. His passing came as a bolt, shattering.

Walking the other day through the Manet/Degas show at the Met, I was reminded as have been many of a time of camaraderie perhaps less scattered by trade and inattention. I would have loved to walk through the show with him, a short way from his elegant haunt in NYU’s Duke House on 78th Street. In memory, we can share a few lines from Stéphane Mallarmé’s “Salut” standing by Édouard Manet’s 1876 portrait of the poet:

Rien, cette écume, vierge vers

À ne désigner que la coupe;

Telle loin se noie une troupe

De sirènes mainte à l’envers.

Nous naviguons, ô mes divers

Amis, moi déjà sur la poupe

Vous l’avant fastueux qui coupe

Le flot de foudres et d’hivers;

Enrique Ramirez, professor, Pratt Institute

I am still grappling with Jean-Louis’s absence in our field—and our world. I first met him in 2007 after an introduction by Claire Zimmerman and Spyros Papapetros. From our conversations, and in my first-ever class with him, it became clear that Jean-Louis was an extraordinary mind who saw architecture as part of a larger historical fabric, a larger-than-life personality that made you feel as if you were part of something bigger and more important. Tales of his kindness and generosity always preceded him, and always exceeded our expectations of what a professor, advisor, and mentor could be. I owe him so much… and miss him terribly.

Simon Sadler, chair, Department of Design, UC Davis

Jean-Louis had no obligation to be as generous as he was with me, and yet he was generous nonetheless. He was a fascinating intellectual, and I feel somehow blindsided by his passing.

Malka Simon, professor, Brooklyn College

Jean-Louis advised me as a PhD student at the Institute of Fine Arts. I remember and deeply appreciate his open-mindedness. His expansive definition of architectural history encouraged my pursuit of topics I had rarely seen addressed in articles and books at the time, such as transportation infrastructure and vernacular industrial works. Jean-Louis never told me they didn’t count as architecture. Rather, he exhorted me to draw up a list of questions I had, and then get to work finding the answers—advice that I still follow, and have passed along to my own students. Jean-Louis’s assessment of that work incorporated gestures and diagrams along with text. Slashing lines and circles scribbled on the back pages of my drafts got to the heart of what I needed to do without the burden of words. Jean-Louis, or JLC, as he always signed his emails, was an efficient communicator. His sharp eye in the field, from New York to Los Angeles and beyond, taught me the importance of looking, seeing, and breathing in architecture where it lives. I was a native Brooklynite writing about Brooklyn factories, but my work didn’t feel provincial because, as a true global citizen, Jean-Louis guided me to find the big ideas and my place within them. I will always be grateful to him for teaching me.

Łukasz Stanek, professor, University of Michigan

Among Jean-Louis Cohen’s many books, particularly important for me was one of his earliest: La coupure entre architectes et intellectuels, ou les enseignements de l’italophilie, published in 1984. This book revisited the relationships between architects and intellectuals in France and their reassessment in the wake of 1968 through exchanges with Italy and the fascination with the intellectual creativity of Italian Marxism. Historicizing this relationship as both a witness and a contributor to the events studied, Cohen reflected upon the historical conditioning of history-writing—an interest and a concern that never quite disappeared from his work. A few years ago, I invited him to share his thoughts about this topic during a symposium at TU Delft focused on the work of Henri Lefebvre. Cohen spoke about the conference Pour un urbanisme…, which he co-organized in 1974 in Grenoble and the related theme issue of la nouvelle critique. He spoke about the sense of hope from which the Grenoble conference originated, about the disappointments that followed, but also how, despite these disappointments, the conference became formative of multiple intellectual projects that continue coming back in unexpected ways—just as Cohen’s own work will.

Marvin Trachtenberg, professor, NYU IFA

While all people are of course unique, a few seem to be gifts to humanity from the gods, and Jean-Louis Cohen was surely one of them. The circumstances of his death are so uncanny, like an inscrutable Greek fable–a wasp sting, at dinner– that one imagines that the Gods took him back–otherwise I almost cannot accept the facticity of this dire turn. In his mid-70s, Jean-Louis was still going full tilt, as I witnessed from my close-up view as a friend and colleague at the Institute of Fine Arts for over three decades. He had many sides, but there was always one that seemed specially focused on his relationship with you, whether in general or at the moment. It was not until after his passing that I realized that whether we were meeting at the Institute, or at home, or out among buildings in Paris, Rotterdam, the Ardèche, or wherever, he always kept the conversation on point and personal. It was another facet of his singular ability to compartmentalize knowledge, relationships, and the workings of his mind, which permitted his extraordinary contributions to architectural knowledge and the well-being of the many worlds he inhabited.

Ian Volner, writer

Jean-Louis Cohen was the preeminent French historian of architecture of his generation. That was always his phraseology : not an architecture historian—the typical English formula, suggesting a somewhat monocular focus—but un historien de l’architecture, a scholar at large who happens to be thinking about design. In the grand art-historical tradition that descends from Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the 18th century, passes through Jacob Burckhardt in the 19th, and fans out in the 20th as architecture came into its own as an object of academic inquiry, Cohen stands as arguably the most important force in consolidating the gains of those early forebears, ensuring that the modernist revolution in design practice received its intellectual due. A necromancer of the archive, he was a total junky for research, summoning forth every forgotten project and accounting for every obscure client and every overlooked collaborator.

He was also at the center of the most important social and political developments of his own time and place, from the May 1968 student revolt in Paris to the redevelopment of the city in the 1980s and beyond. And his influence goes further than that. The online vogue for Cold War–era Brutalism? Soviet design history as we know it effectively begins with Cohen. Critics sifting through the fallout of the “starchitecture” phenomenon? Cohen literally wrote the book on Frank Gehry. Le Corbusier on a 1920s cruise ship with Josephine Baker, Mies in 1930s Berlin with a guilty conscience, Jean Nouvel in a 1970s nightclub… Cohen knew where architecture kept the good stuff, and he would share it liberally with whomever asked.

He was an incredible teacher, and being his student was an absolutely terrifying experience. Even as I write this, I think of his particular, Gallic way of exhibiting qualified disapproval for any statement he thought too stupid to accept but just novel enough to merit interest. Raising his right hand, he would wave it slightly from side to side; his head would move in tandem, he would frown, and then he would emit a sort of suspended hum, like the sound of a distant chainsaw cutting through a very small tree. It was devastating. And it was wonderful.

Nader Vossoughian, professor, NYIT

By his own account, Jean-Louis was not an architectural historian, but rather an architect and historian: “I have always found the title ‘architectural historian’ to be strange,” he once said. He refused to separate the built environment from culture at large: “I subscribe to Rossi’s belief, articulated in Architecture of the City, that the city is an artifact. I am interested in the city as an artifact, a collective product of technology, culture, and art.”

I had the pleasure of studying under Jean-Louis a number of years after completing my doctorate. He was a mentor and colleague to whom I could turn for scholarly insight and advice. The last time I saw him was this past spring, at a reception honoring a mutual colleague and friend who was moving back to Europe. I relayed to him a funny anecdote that I had heard about his scholarly output, which had been immense of late. “It’s like all you have to do is push a button, and a new book comes out.” I cannot remember his response verbatim, but here is the gist of it: “It’s the culmination of 30 years of research. The best is yet to come!”

Jean-Louis’s untimely death throws into question whether the projects on which he was working at the time of his passing will ever see the light of day. Indeed, it could well be said that he died a “young” scholar despite being 74 years old and despite having already published countless books and articles. He never explained to me personally what he had in store, but we do have a pretty good idea based on a tribute published on LinkedIn by the Canadian Centre for Architecture, which revealed a project on North Africa that was to be cocurated with Samia Henni.

I offer my condolences to Jean-Louis’s family and loved ones. I am also telegraphing my thanks to him personally.