Each morning, like clockwork, Albert Einstein and Kurt Gödel walked from the town of Princeton, New Jersey, to their offices at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS). Founded in 1930 with an initial gift of $5 million from siblings Louis Bamberger and Caroline Bamberger Fuld (their family operated a successful department store in Newark), the IAS gathers scientists and scholars to expand the limits of human knowledge. As they peregrinated, Einstein and Gödel—the one the inventor of the theory of relativity, dressed in professional “baggy pants held up by suspenders,” the other the “greatest logician since Aristotle,” decked out in “a white linen suit and matching fedora,” according to science author Jim Holt—chatted “animatedly” in German about what was on their minds.

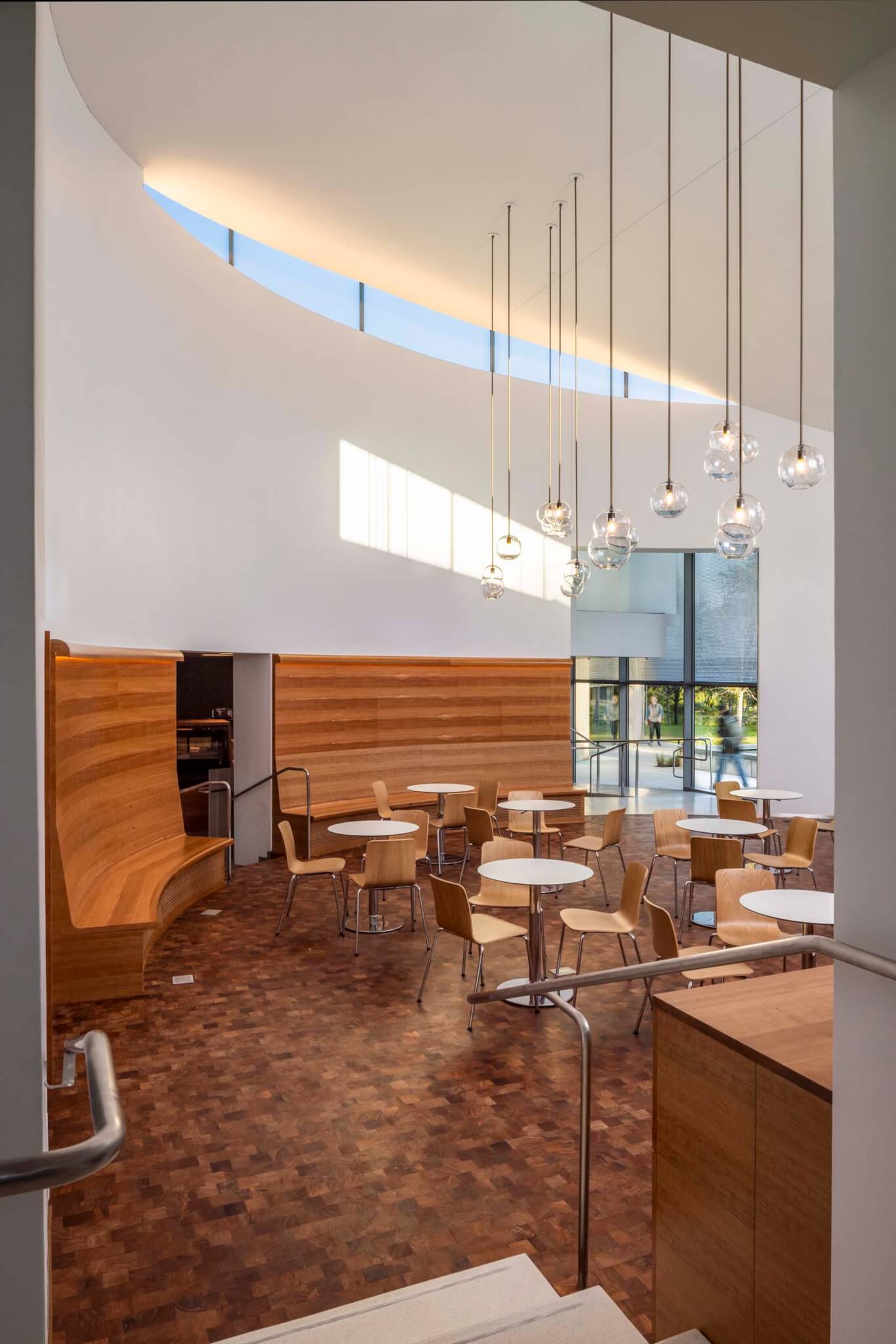

Had the famous duo commuted today, they would’ve likely walked by—or through—the Rubenstein Commons, an addition to the campus completed late last fall by Steven Holl Architects (SHA). The building, which stages a set of handsome rooms across its sloping site, aims to be a salon of sorts, coaxing scholars (numbering nearly 300 this year across four schools: mathematics, historical studies, natural sciences, and social science) out of their individual thought bubbles into shared dialogue. SHA has shaped the malleable program of meeting spaces—study desks, conference rooms, and a lecture hall, with connective zones for lounging and dining, linked by a cafe—into a sequence of light-filled pavilions. Enclosed with 49 precast concrete panels and topped with arcing roofs, the project’s tidy 17,000 square feet are spread over a main floor, a mezzanine, and an infrastructural basement. The two wings of rooms meet in the middle, where a low, wood-ceilinged bar is located; whereas the outer spaces are open and airy, near the bar the interior tapers to a glassed connector only about 12 feet wide, evidence of skillful shaping of compression-and-release volumetrics.

The Commons sits between Fuld Hall, IAS’s original building designed by Jens Frederick Larson and completed in 1939, and, across a stream, the scholars’ housing, originally designed by Marcel Breuer in the mid-1950s. Replacing a surface parking lot, the Rubenstein Commons joins a campus of other academic buildings designed by Wallace K. Harrison (a library for historical studies and social science), Cesar Pelli (Simonyi Hall and Wolfensohn Hall), and Robert Geddes (Bloomberg Hall) in the leading styles of their respective eras. Geddes previously designed Simons Hall and West Building, both completed in 1972, and the former includes the institute’s dining hall. Beyond, about 700 wooded acres (of the institute’s 800) are threaded with trails and dotted with public art.

Holl won the project in 2016 in a closed competition, after besting proposals from Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, OMA, and MOS. Contextual sensitivity was key to his winning scheme. The ensemble of dancing roofs (engineered by Guy Nordenson and Associates) is clad in copper, linking them to those of Fuld Hall. Similarly, the smooth concrete connects to that of Geddes’s politely Brutalist first contribution, mirroring it across the campus’s north-south axis. In pitching the project, Holl also explained the effort using analogies from mathematics and science: “Space curves,” splining in three dimensions, establish the Commons’ overall geometries.

The logic of intertwining, as distinct from the roof-shaping space curves, braids together rooms of varying sizes, experts from an array of disciplines, and pathways to and from everyday destinations using techniques Holl has honed over the decades. (Intertwining is, of course, Holl’s second monograph, from 1996.) The rooftop ballet, an idea seen in his Stretto House in Dallas, completed in 1991, caps a Tetris-like puzzle of precast, a tactic used in the Glassell School of Art in Houston, finished in 2018, which has roots in his (and Vito Acconci’s) facade for the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York, finished in 1993. The knot-like stainless steel door pulls resemble those of the 2017 Lewis Arts Complex across town at Princeton University. (Both were made by local metal artist François Guillemin.) Inside, the sculpting of light evidences a skill brought to bear on so many of SHA’s projects.

On-site, Noah Yaffe, SHA’s partner in charge for the project, remarked that part of the aim was to create a living room for scholars where they’d want to hang out for extended periods of time, before and after business hours. To that end, well-crafted, residential-scale details set the mood. The cherry seating, doors, and Duratherm windows; mesquite end-grain flooring; comfy furniture; and custom carpets designed by Holl all create an atmosphere of warmth. Overhead, cast-glass fixtures of intersected spheres, illuminated from within, add to the sensation, as do the 21 clerestory pieces of prismatic glass, whose sawtooth profile (milled, not cast) splays light into its rainbow spectrum. Above heated terrazzo floors, slate walls accented by linear cherry lights offer expanses for chalkboard exchange. (For the record, the institute’s mathematicians favor Hagoromo Fulltouch chalk.) On a visit in late autumn, the building was quiet as its finishing touches were being applied, but already pairs of thinkers were scribbling away, their equations filling the inky voids.

Although the project was reduced from the competition entry—there are five space curves, not seven, and three water features, rather than four—Holl’s concept still shines. Indeed, everything about the construction by W. S. Cumby is so well resolved that what may be minor missteps are heightened. As much as the project relies on circulatory reasoning, the straight shot of asphalt sidewalk on the eastern approach is awkwardly misaligned with the door. And if one wants to follow the path outdoors instead of being routed inside, there are steps with no ramped alternative for ADA accessibility. Above, the copper roofs, which have already begun to patinate, lack downspouts, so their runoff stains the concrete green.

Beyond those construction items, another conceptual wrinkle persists. In an essay written during the project’s design and construction, architectural historian Anna Bokov contextualizes Holl’s claim that the Commons acts as a “social condenser.” (Bokov was a visiting scholar at IAS when her book on Vkhutemas, a Russian state art and technical school, was published in 2020.) The typology arose in the 1920s, with the Rusakov Workers’ Club, designed by Konstantin Melnikov and finished in 1928, standing as the most impressive built example. The ideal architectural form of the social condenser was intensely studied at Vkhutemas, and Bokov surfaces a student project from the “space course” whose curves bear a notable resemblance to those of Holl’s roofscape. While the architecturally abetted swirling of people and ideas is similar to this precedent, it is a stretch to cast IAS’s scholars as workers in need of recreation. The leap also obscures the mission of the original social condensers, which were designed to inculcate users in socialist ideology, while IAS’s version, with a naming gift by David Rubenstein, is funded in part by private equity ROIs.

Referential quibbles aside, SHA’s building—with its material warmth and expert handling of daylight—seems a welcome addition to IAS’s campus. Einstein famously roasted the town of Princeton as “a wonderful piece of earth, and at the same time an exceedingly amusing ceremonial backwater of tiny spindle-shanked demigods.” Now IAS’s Nobel-dense outpost on Einstein Drive has a new watering hole. It’s not outrageous to think that what starts as a Twombly-esque wager on the Commons’ blackboards might, in the decades to come, change the world.