It wasn’t long ago after Dasha Zhukova opened Moscow’s celebrated Garage Center for Contemporary Art in 2008 that she began to chafe at the limitations of presenting culture within a high-art temple. Looking to move beyond museum walls, Zhukova started organizing other kinds of art experiences. She launched a film festival, founded an art magazine, and joined the board of The Shed in New York. But her ultimate goal, she told Art News in 2021, was to embed art in “the day-to-day environment.”

That quest eventually led to real estate development. At the height of the pandemic in 2021, Zhukova formed the housing company Ray, with the aim of building apartments that would make art experiences a natural part of daily life. There would be quality art in her apartment buildings’ public spaces, art exhibits and openings, master classes for residents, studios where residents could indulge their creative impulses, and maybe even a few actual artists. But mainly the complex would house a community of sensitive souls united by their affinity for art.

The prototype for Zhukova’s concept opened this spring in a former industrial corridor in Philadelphia’s fast-changing South Kensington neighborhood and will be followed in 2025 by Ray Harlem, at Fifth Avenue and 125th Street. “Ray is more than a building,” Zhukova’s promotional materials proclaim. “It’s a place.”

It’s also an exercise in canny branding, albeit a very earnest one.

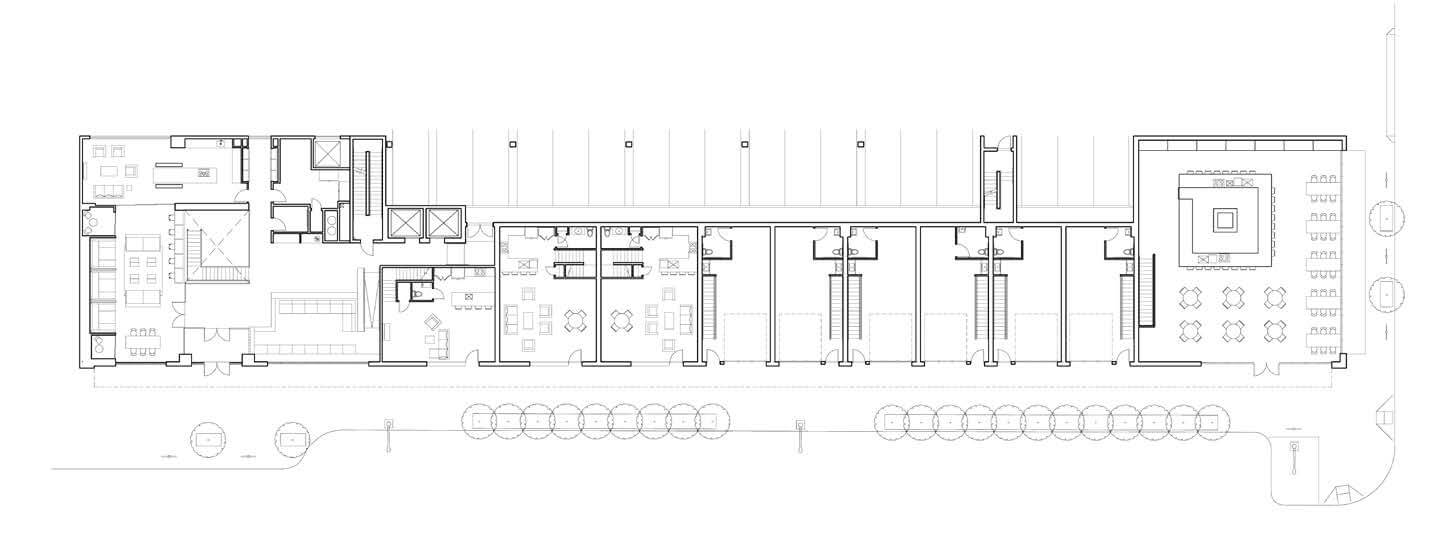

That branding is evident even before you walk in the door of Philadelphia’s new Leong Leong–designed apartment building. A row of six roll-up, glass-fronted garage doors line the ground floor on North American Street. They’re meant as studio space for artists and arts-adjacent makers. Ray commissioned Philadelphia artist Michelle Lopez to produce an “intervention” at the top of the building’s brick parapet: a text fragment that reads When Under One Sky. The piece could almost be a ghost sign, a survivor from South Kensington’s hardworking past.

It’s become practically de rigueur for high-end residential developments to include an “art program” in their public spaces. What elevates Ray Philly above the luxury crowd is Zhukova’s knowledge of contemporary art. The sunny lobby is dominated by a site-specific sculpture by Rashid Johnson, whose sought-after work deals head-on with the contradictions of the Black experience—he once painted the words “I Talk White” on a mirror. It’s true that his Ray Philly piece isn’t quite so provocative: The gridded structure could easily be mistaken for a shelving unit if it weren’t for several intriguing sculptures perched among the potted plants. But nor is it the usual, clichéd black-and-white photo of an urban scene. The large wall hanging over the central staircase, by Philadelphia artist Marian Bailey with production facilitated by Commonweal Gallery, picks up on the nature theme and depicts a pretty Black woman peering through tropical foliage.

These complementary elements suggest there is a larger aesthetic at work. Rather than outfit the lobby with the obligatory living room trio—two armchairs and a sofa— Ray’s designers installed a forest-green conversation pit that encourages residents to sit close and interact and, ideally, form friendships. The pine-colored coffee tables and benches are generously strewn with art books printed on heavy-stock paper, including a door-stopper of a monograph devoted to Johnson’s work. While Ray Philly offers the usual selection of apartment amenities—coworking, event kitchen, roofop deck—there’s also a basement workshop that residents can reserve for messy art projects.

As architect Dominic Leong explained, “We got involved in Ray around a conversation: What is community today? What are the needs of living?”

Initially, it looked as if Ray Harlem would be Zhukova’s real estate debut. She had partnered with the National Black Theater, which owned the Fifth Avenue site, to build two new theater spaces in the base of a new 21-story tower designed by Frida Escobedo with Handel Architects. But because of permitting complications in New York, the 110-unit Ray Philly opened first.

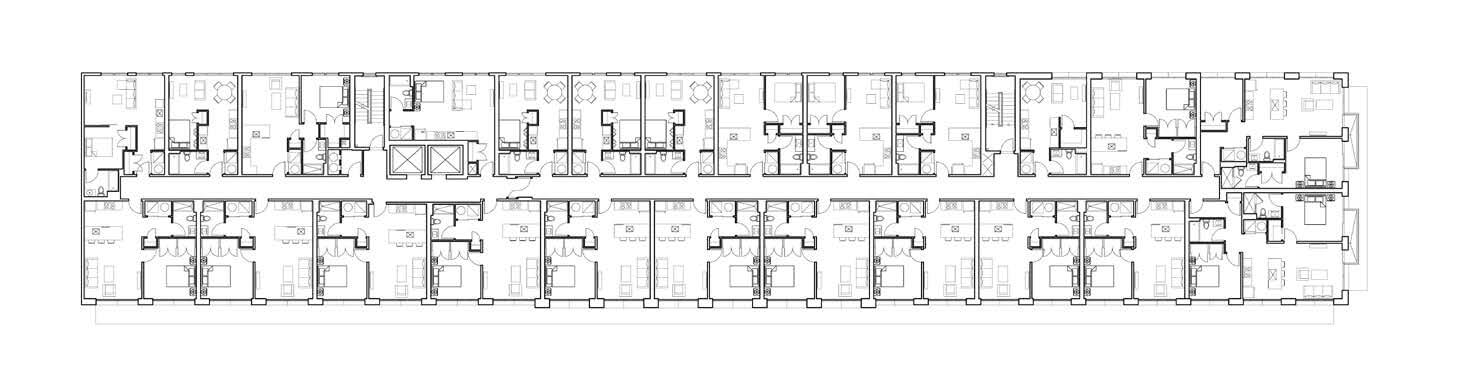

Building Ray Philly turned out to be more straightforward because Zhukova purchased the site from a developer who had already obtained all the necessary city approvals. But the prepackaged deal came with a big downside: The architects, brothers Dominic and Chris Leong, were locked in on the massing, a five-over-one bar building that stretches 310 feet from end to end. The Leong brothers told AN they were determined to elevate the building type, which has become the bane of cities, into real architecture.

They’ve done just that. Their treatment of the facade and ground floor is easily the most artful thing about Ray Philly and especially welcome given what else is being built nearby. Only a decade ago, North American Street was lined with muscular, brick factories and sturdy working-class row houses. But the surrounding area, often called Fishtown, has been rendered unrecognizable by new residential construction. Many of those newcomers are five-over-one buildings faced in metal panels. Their flat, lifeless surfaces are typically arranged in alternating color patterns, ostensibly to “break up the massing,” which ends up calling more attention to their clumsiness.

Rather than succumb to that approach, Leong Leong clad its building in Philly’s vernacular red brick. That choice alone would have made Ray’s facade above average, but the office used the brick in a novel way to create a highly textured surface that resembles tile. Leong Leong literally turned the bricks inside out: Each one is split lengthwise, then set with its broken, three-pronged core facing the street. Once the designers opted for brick, they decided to lean in, using matching red grout and red concrete to deepen the effect.

Such a long, red building might have overwhelmed some other locations, but one of the few industrial survivors on North American Street is the 340-foot-long, all-brick Crane Building, designed by Philadelphia architect-engineer Walter Ballinger in 1905. The old factory, which sat derelict for years, was rescued in 2006 by developer David Gleeson, who transformed it into a hive of studios for artists and architects. Since then, the stretch between Master and Oxford streets has emerged as an accidental culture hub that includes Nextfab, a coworking space for makers, and the Clay Studio, a ceramics workspace and museum designed by the award-winning Philadelphia firm Digsau. Ray Philly fits right in.

The street-facing artists’ studios are also a welcome innovation. As online shopping has devastated brick-and-mortar retail in cities, it’s become increasingly difficult for residential developers to find tenants for traditional shops. The studios offer an alternative way to activate the street. While not all the studio tenants will actually be wielding paintbrushes or chisels, most have some connection to the arts. One space will be occupied by a gallery, another by a commercial photographer- slash–branding consultant. Ray has also hired a full-time programming coordinator to work with the studio tenants and help them organize public art events.

Still, there is something ironic about building a high-end apartment building for art lovers in a neighborhood that, only a few short years ago, served as a haven for artists seeking cheap studio space. It’s unlikely that many Philadelphia artists can afford a $1,800 one-bedroom apartment at Ray Philly. It seems they’ll have to make do with a building that encourages its residents to appreciate and, hopefully, buy their work.

Inga Saffron is the Pulitzer Prize–winning architecture critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer.