Located at the confluence of the Sea of Cortez and the Pacific Ocean, Mazatlán was called Mexico’s “Pacific Pearl” in the 1950s, when it was a favored destination for Hollywood stars. In recent years, there has been an attempt to revive some of Mazatlán’s bygone luster. The city’s historic center has been meticulously restored, and some of the midcentury mansions dotting its hills are yet again hosting visitors drawn by the area’s cultural and natural wonders. The crown jewel of this comeback effort is the city’s grand new aquarium, one of the most anticipated projects of new architecture in Latin America. Designed by the studio of Tatiana Bilbao, in person the building defies expectations, refusing to play subtle or inviting. Instead, the Mazatlán aquarium’s new home is a monumental rationalist structure, entirely made of rose-tinted concrete, that looks like a stranded Dune set.

That’s not a bad thing. On multiple visits, the Brutalist building was full of life, both the myriad sea species it’s home to and countless families visiting it. Since opening last May, it is evident the aquarium’s massive walls serve their purpose well, making a bold statement while letting the building’s contents—the formidable natural wealth and variety of the Sea of Cortez—be the star.

The Gran Acuario de Mazatlán is the brainchild of Ernesto Coppel, a local business magnate who has led an ambitious initiative to broaden his hometown’s appeal for visitors (surely so they spend an extra night or two at one of the hotels he owns). Bilbao had already been tasked with reinvigorating the city’s long-neglected and heavily polluted Parque Central, a long green expanse running parallel to the coastline. Then in 2017, her office got the commission for the aquarium, sited on a 6-acre plot at the park’s southern end. The $100 million project was jointly financed by Coppel and the state, with public land leased to the privately operated aquarium.

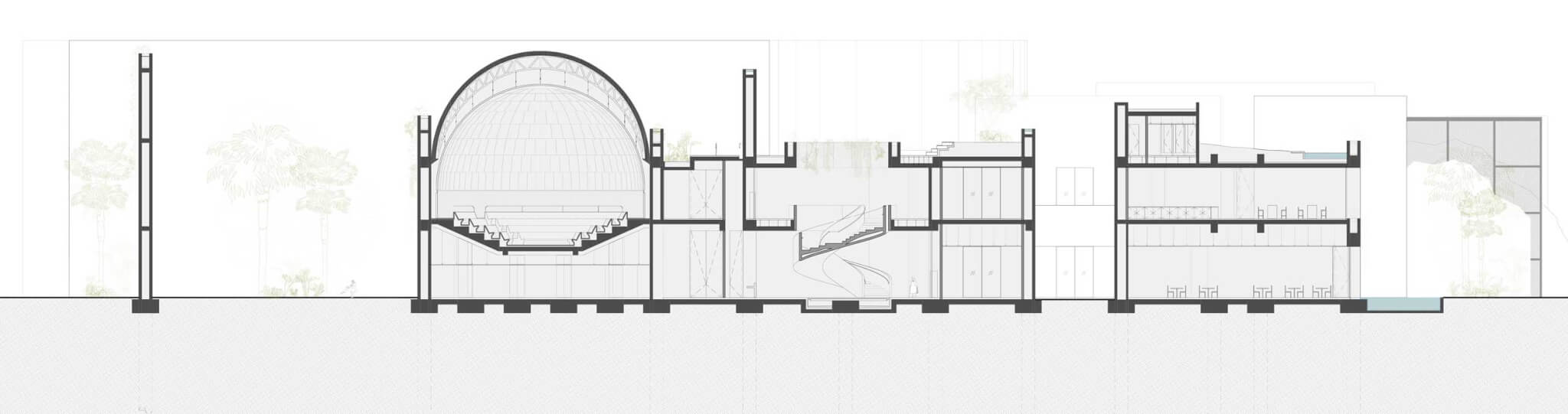

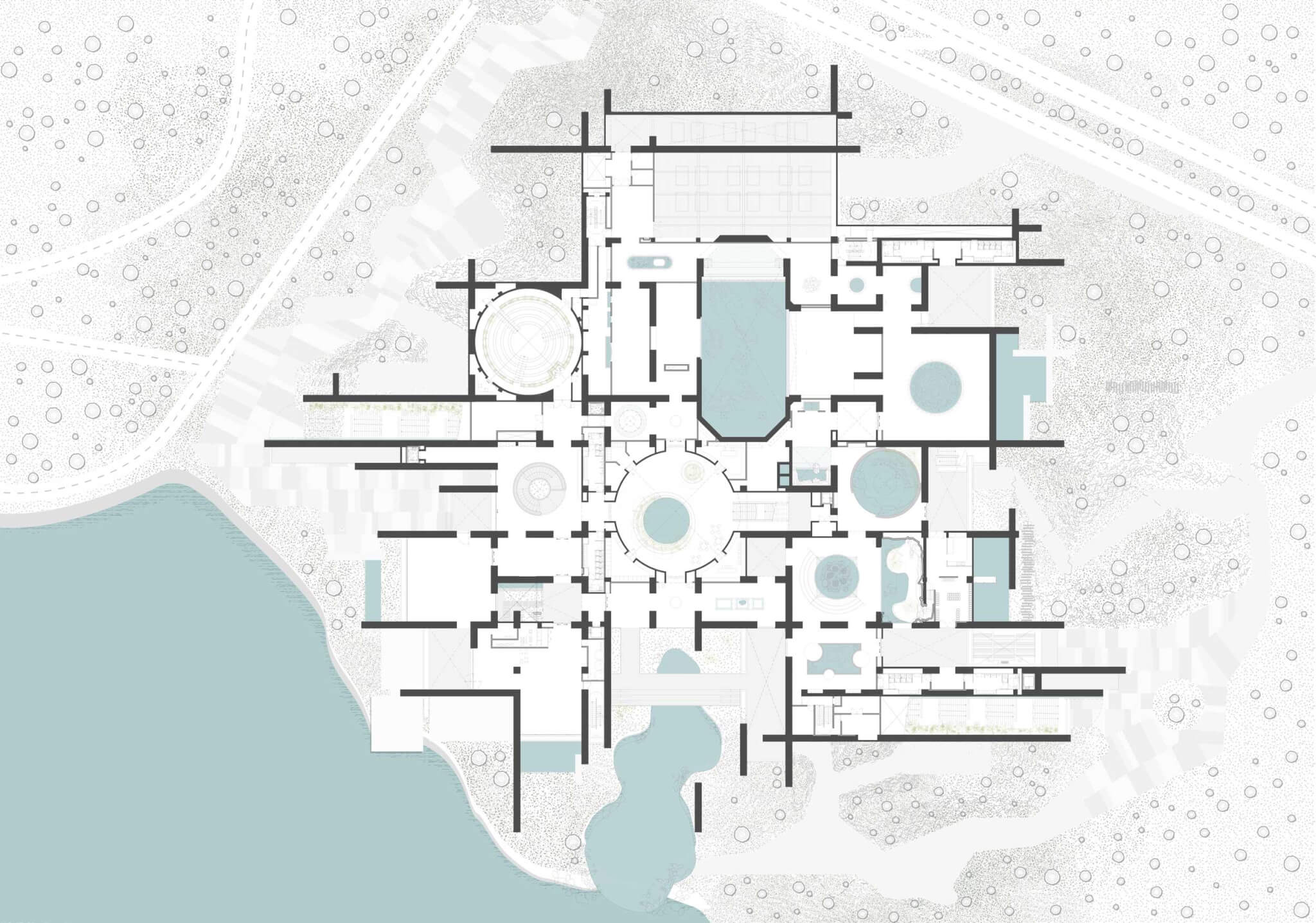

For a structure of its scale—a total built area of 186,000 square feet with walls reaching 74 feet in height—the new aquarium is strikingly isolated from the surrounding urban landscape. It’s enclosed on all sides. A busy road flanks its fenced eastern edge, and its form is hidden from the south by various constructions, including the old aquarium building. It’s also cut off from Mazatlán’s prized waterfront to the west both visually and physically—a newly sanitized lagoon separates it from a string of speculative high-rises along the beach. Most perplexing is the new aquarium’s lack of integration with the park to the north, especially considering Bilbao’s involvement.

Once it does appear, the aquarium is a captivating sight, mysterious, strikingly uncontemporary, and severe in its bunker-like massing. Even though there’s an elegance to the vertically staggered, 3-foot-wide slabs of concrete that define it, this is a willful composition that resists easy categorization or comprehension. In fact, the aquarium’s most striking vista is not of one of its elevations—none of which is particularly legible—but its plan. Seen from above, the building appears as a gridded system whose intersecting walls form a series of round and rectangular chambers. Beyond its forceful form, the building’s most indelible feature is the concrete’s mauve shading, part of an effort by the architects to temper the rigorous rectilinearity and stark tectonics.

To enter the aquarium, visitors are expected to go up a 112-foot-long ceremonial staircase (a small elevator is tucked to the side). The ascent leads to the roof, where planted walkways create a pleasant (albeit shade-free) landscape pierced by a large central cylinder. The visitor is now required to descend more stairs into a courtyard at the bottom of this rotunda. In spite of the 44-foot-tall curving walls that enclose it, there is a human dimension to the round plaza, which, with its cafe and fountain, is the first space one encounters in the building whose solemnity feels welcoming.

If the prescribed approach seems capriciously convoluted—not to mention impractical for a building expected to draw thousands of daily visitors—it serves an elaborate narrative Bilbao and her office like to cite as the origin of their design.

Faced with having to design a huge edifice with a set of specialized requirements in a matter of weeks, the team came up with the idea of an abandoned building designed for an unknown purpose at an unspecified point in time. As the ocean waters rose, the walled warren of spaces was submerged, only to one day reemerge with its rooms filled with marine life that claims the superstructure as its home. Entering the building from above is intended to convey the visitor’s submersion into this mythical, pseudoarchaeological realm, while the water running down walls at various points reinforces the fictional inspiration. It’s all a little corny and literal, and, at the same time, admirable in its imaginative panache and the architects’ determination to see the fantastical conceit through.

The circular plaza segues into a vestibule with a spiral staircase that unfurls under an open oculus. It is here that the actual aquarium begins. The promenade conceived by Bilbao’s studio is both effective and evocative, with spaces that transition effortlessly from indoor to outdoor. Even “interior” rooms are in fact only semi-enclosed, lacking doors or windows so the entire space feels like an open-air structure.

The exhibitions unfold over 19 rooms, following a progression from land down toward the canyons at the ocean’s bottom. Designed with the Vancouver-based conservation organization Ocean Wise, the displays are enlightening but never condescending, aiming as much to entertain and delight as to educate visitors of all ages about the abundance and intelligence contained in our seas—as well as the ways humans endanger the same treasures.

The aquarium’s rose walls never remind the user too loudly of their presence. The architecture becomes a kind of integral skin, with built-in recesses, nooks, steps, benches, terraces, and cenote-shaped light wells carved out of the thick concrete to cradle a mangrove or turtle basin.

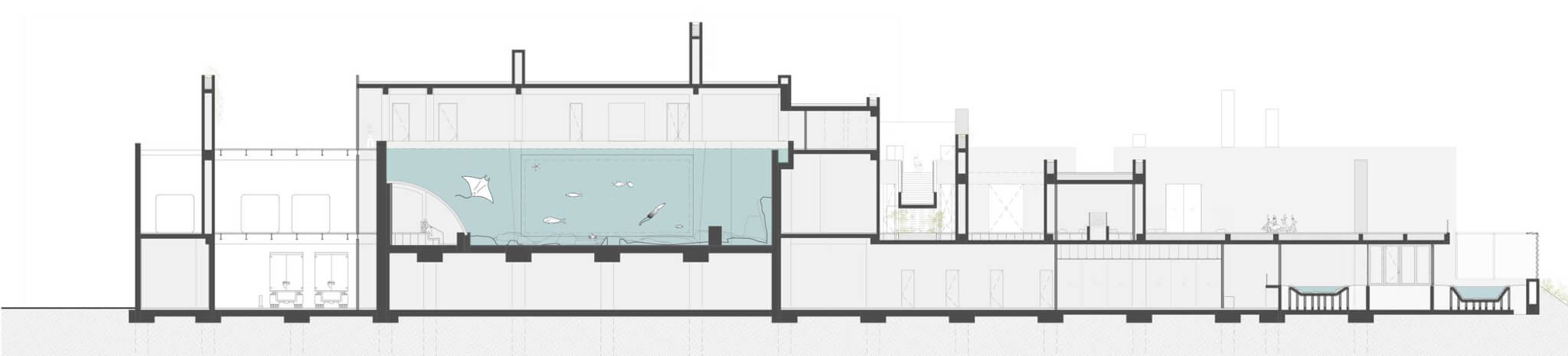

The sequence builds up to the aquarium’s most dramatic displays, held in the two largest, dimmest rooms. The first houses cylindrical floor-to-ceiling tanks devoted to colorful coral life. These are followed by the building’s centerpiece, a hall that functions as a kind of cinema with the screen replaced by one face of a gigantic water tank filled with sharks and other ocean dwellers. (Like all of the aquarium’s thick acrylic panes, the Kobe, Japan–based firm Nippura manufactured the 43-by 29-foot panorama.)

After viewing the exhibitions, visitors can take the spiral staircase down to the ground-floor food court and additional public gathering spots. The aquarium’s offices are also on this level, as is an area with the advanced filtration and life-support technologies needed to sustain and clean the tanks above. A third floor is reserved for research, biologists, and veterinary staff.

In an interview at her Mexico City office, Bilbao explained her design’s imperative to respond to natural conditions and convey permanence. “It needed to be a robust building, to imply that it’s been there forever and will last for a long span of time. Our main objective was to create a building that flows openly between inside and outside and fosters a natural relationship with its environment.” In practical terms, the building needed to withstand extreme humidity, heat, and hurricanes characteristic of the climate. The sturdy materiality, weathered from the onset, as well as the breathing openness of the aquarium’s complicated plan suggests a man-made ecosystem both alien to nature and destined to be appropriated by it. Its exposed expanses are primed to be co-opted by time, vegetation, light, and the elements.

As for the building’s unexpected formal language, Bilbao claims it’s a direct result of the “flooded ruin” premise her studio concocted: “We didn’t design it around a program, but as a set of walls that open and enclose different spaces, without regard to predetermined specifications other than the need to create an experience.”

Bilbao also acknowledges that the building’s reliance on concrete, a leading source of CO2 emissions, can be regarded as at odds with the aquarium’s mission to raise awareness about the need to take better care of our planet. “[Based on] the way sustainability is measured now, which I don’t believe makes sense, it’s not a sustainable building. But you could also consider it’s a structure that could last a thousand years and be inhabited in a variety of different ways in the future, so you could say that durability and versatility offset the resources used to build it.”

On a recent weekend, the building’s shortcomings seemed moot, considering its successes. Visitor numbers have surpassed projections, and invariably, guests appear mesmerized by what they see. The building’s lack of overly refined details suits not just the climate and heavy traffic but also the fact this isn’t an art museum. Snacks are sold in some of the interstitial open spaces between exhibition areas, and visitors are allowed—with protective precautions—to interact with the animals. As the aquarium’s executive director, Rafael Lizárraga, put it on one of my visits, “Our reason to exist is the conservation of marine life. We’re both a tourist attraction and educational facility, with a special mission to support species at risk.” It will take time to assess if the Gran Acuario lives up to its noble objectives. For now, Mazatlán has an impressive new landmark worthy of its storied past, and its manifestation of Bilbao’s architectural imagination makes it all the more remarkable.

Suleman Anaya is a regular contributor to PIN-UP, The Architectural Review, and Aperture living in New York and Mexico City.